In this article, I’ll include excerpts from a recent sermon and share some thoughts about sermon preparation and delivery. Every pastor prepares sermons differently. My goal here is a combination of mechanics and approach―how to best capture and communicate what God is doing with what He’s saying, and to deliver shorter, more effective sermons.

All the examples which follow are from a sermon on Acts 8:2-25, titled “Peter and the Magician.”

Introductions

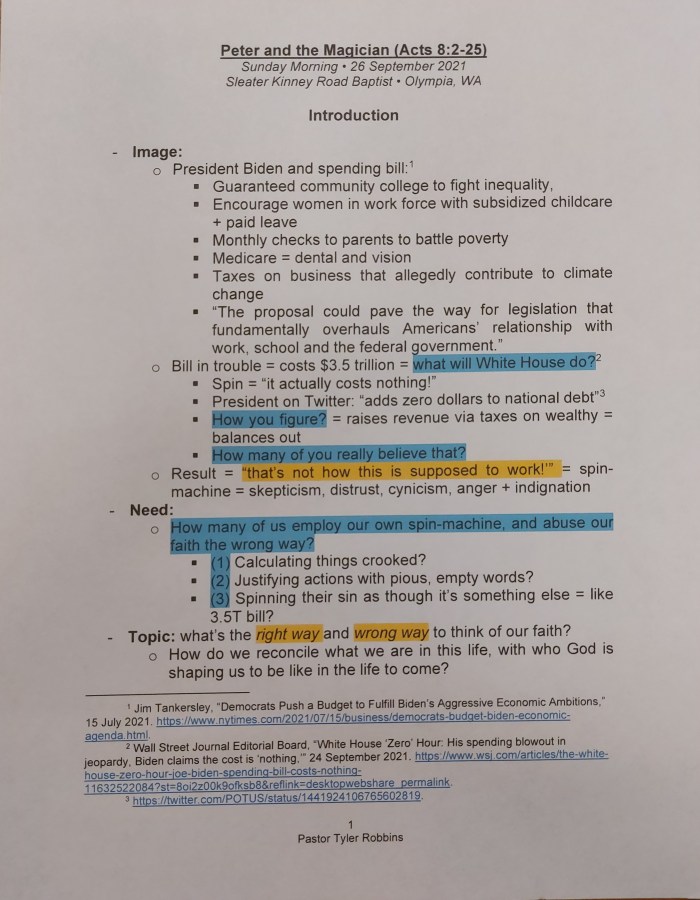

The introduction and conclusion are now the only portions of my sermons I script. Here is the introduction:

I use Abraham Kuruvilla’s acrostic “INTRO method,” which takes strong discipline but is well worth it (A Manual for Preaching: The Journey from Text to Sermon (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2019), ch. 7). I leave it to the reader to seek out his text and read the approach for yourself, but you can see it in my outline.

You begin with a striking image that grabs people’s attention, to get them to commit to listen to the sermon in those first crucial minutes. I never use books of illustrations or scour the internet. I read quite a bit and my illustrations usually come from (1) news stories I read, (2) historical anecdotes, or less often (3) stories from my law enforcement and investigations career. You must be able to make some kind of tangible leap from the illustration to the substance of the sermon.

You then pivot to ask probing questions, to get the congregation to see why they ought to listen―why they must listen. You should never tell people the application or reveal “what God is doing with what He’s saying” in the introduction. Do. Not. Do. It. You are not a lawyer, making an argument. Don’t lay out a precis of your “case,” then spend the sermon “proving” it to a jury. Just ask questions that provoke introspection, related to the application move that is implicit in the text. In this case (see above), you can see where I go with my questions.

I then switch to a general statement of the topic, usually in the form of a question to be answered. Again, do not unveil your application or the force of the passage.

Then, state the passage text and lay out a “contract” of sorts by providing the structure of the sermon―the “moves” you’ll be making, so the congregation can follow your progress. Kuruvilla sums it up well (Manual, p. 191):

The Image says: Get ready to hear this sermon.

The Need says: This is why you should hear this sermon.

The Topic says: This is what you are going to hear.

The Reference says: This is from where you are going to hear it.

The Organization says: This is how you are going to hear it.

I try to keep my introductions to four minutes. I made it with this sermon. However, this past Sunday (16 October 2021), it ran to 5:30. You can’t win them all … I did this introduction in about four and a half minutes:

Move 1―The Scattering

Here is where my newer method for preparing my notes takes form. I include virtually no notes at all. I simply highlight key things I wish to emphasize, and insert terse comments on things I want to be sure I don’t blank out on as I’m speaking:

This is where my choices for emphasis might raise some eyebrows. As I said in a previous article, I don’t think “audiobook commentary” preaching is real preaching at all. So, I don’t comment on everything in the text. I leave a lot out. I only highlight the key points that I believe God would have us “see” in the text, in light of what I believe He’s “doing with what He’s saying.”

So, this means I do not dwell on the nature or extent of the persecution. I basically let the text float me along and only make a few comments. I note Luke’s interesting word choice to describe Paul’s fanaticism, but move quickly. I cover vv.1-3 in perhaps two minutes. I believe it is a mistake to park here and chat about persecution. That is a worthy topic, but it isn’t Luke’s point in this passage. It is an appropriate topic for the confrontations with the Council at Acts 3-4.

Acts 8:4-8 present another challenge, and another opportunity to resist audiobook preaching. How many of us are tempted to stop with Acts 8:2-8? The problem is that this is only setting the stage for the real point of the passage―Simon’s conversion and his confrontation with the Apostle Peter.

Don’t get me wrong―you can do something with Acts 8:2-8. I just don’t believe you’d be sensitive to the “connectedness” of the passage if you did. This section sets the stage; it isn’t meant to stand on its own. Don’t cut it here and make a sermon about persecution + evangelism, then conclude with a flourish with something like “the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the church!” What are your people supposed to do with that information? They’ll have heard a lecture, not a message aimed at transformation.

So:

- I resisted the urge to speak on the apostolic sign gifts. I mentioned them, but didn’t park there. I emphasized they were markers of God’s kingdom power breaking into a black and white world with brilliant colors.

- I spent more time emphasizing the “paid attention to” remark, which Luke repeats several more times. It’s critical to understanding Simon’s mindset, and his actions.

I covered vv. 4-8 in four minutes. The entire sermon is 11 minutes long, as I finish v. 8.

Move 2―The Magician Joins the Family!

Now we move to the heart of the passage, and this is where I spend most of my time:

My notes speak for themselves, so I won’t belabor the point. Notice that I have no “notes,” in the traditional sense. I’m working entirely from highlights, with some occasional cryptic notes that I want to be sure I remember to emphasize. My hermeneutical aim is to focus on the way Luke juxtaposes the allegiance shift from Simon to Phillip. This is critical. You cannot miss this in favor of speculation about the genuineness of Simon’s faith. Commentators will do this. Ignore them. It’s irrelevant to Luke, it’s irrelevant to you, and it’s irrelevant to your congregation. Luke is not interested in Simon’s salvation―he’s interested in his reaction to Peter and John when they mediate the gift of the Spirit!

It’s the allegiance shift that’s important, because it sets up Simon’s reaction at the forthcoming “Samaritan Pentecost.” Notice that the Samaritans previously “paid attention” to Simon, but now they’ve “paid attention” to Philip. Notice also how Simon encouraged people to give him quasi-worship. This should be your focus. But, again, it cannot end here. Don’t cut your sermon and tell folks to return next week―that would be awful! Move quickly to the confrontation.

I covered vv. 9-13 in five minutes:

Move 3―The Confrontation (Pentecost 2.0)

I’m still not quite at the crucial part of the sermon. Rather, we have here the final piece of the puzzle that sets up the event:

I spend little time on this―I want to hasten on. My focus is not on the theological implications of the Samaritan Pentecost, though I do mention it. Instead, my focus is on the fact that Simon, the magician who had used dark arts to deceive many, literally sees something more powerful, more awesome than anything he’s ever seen before. What would a man like Simon do, in this circumstance? He’s an immature professing believer―what will he do?

My short notes reveal I don’t tarry long, here. I do something unusual and script a list of rhetorical questions to ask the congregation, because I want to get this right. I cover vv. 14-17 in less than two minutes:

Move 4―The Confrontation (Simon and Peter)

Now, we get to it:

This is the heart of the sermon. This is where Simon’s request to Peter can be seen in a holistic light. The guy is reverting back to type; he sees a chance to obtain some of the notoriety he once had while still serving God. He’s bitter, envious, chained up by his own sin. Simon wants his social position back, and he sees a “good” way to get it.

This is more “real” than viewing Simon like a Looney Tunes character and declaring he was a heretic, or “immature.” That’s no good. He was a real person. We’re real people. We do things for the wrong reasons. We lie to ourselves. We “know better,” but we do it anyway.

Again, I script a few particularly important notes, but I basically survive with highlights and terse comments in the margin. I covered vv. 18-24 in just over seven minutes, by far the longest time I parked during the sermon:

Exhortation

I again follow Kuruvilla’s formatting, here, and use a “Tell + Show + Image + Challenge” approach. In this sermon, I ditched the last “image” and only used three elements. Again, I fully script the conclusion because it’s important to land this plane well:

Some final thoughts

My burden here is to share my new method for sermon preparation: no manuscripting, highlights for important things, terse comments in the margin for very important things, and scripted comments only for the most critical items.

This style requires a certain comfort with extemporaneous speaking, within limits. It also takes ruthless message discipline―a quest to go beyond exegesis to synthesis, a sensitivity for genre, an eye for natural thought-units, and an ability to sift the considerable chaff out of the commentaries. It also demands a relentless focus on application―on practical sanctification. How will God’s implicit movement to action in this passage make our congregation more like Christ, corporately and individually? What does God want us to do with what He’s saying? Concretely, exactly, not abstractly?

I’ve found this new style is working for me. The sermons are shorter, tighter, more focused, more direct, more helpful. They take much less time to prepare. It may not work for you. But, then again, perhaps my thoughts here can be helpful to you.