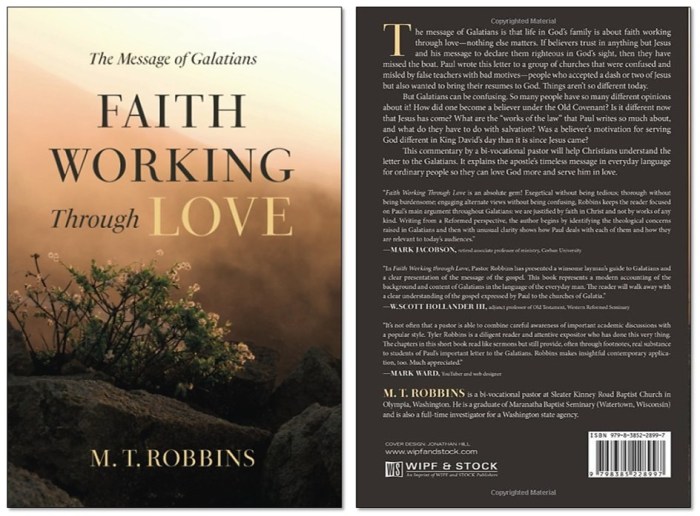

My book about the apostle Paul’s letter to the churches in Galatia is 50% off (through 30 Nov) if you purchase it from the publisher. You must use the promo code CONFSHIP. If you select Media Mail, shipping is free!

Category: Uncategorized

Identifying and Avoiding False Teachers

False teachers are a big deal in the bible. Here, I’ll answer three important questions about them that ought to help every Christian be on guard against their tricksy ways.

Q1: What is a false teacher?

The apostle Peter has a lot to say about false teachers. So does Jude. It’s possible that Jude had Peter’s second letter and borrowed a lot of his material for his own letter. If you read them, they sound similar! What, exactly, are false teachers? What makes them “false”? Both authors sum it up very simply:

- Peter says they “secretly introduce destructive heresies, even denying the Master who bought them …” (2 Pet 2:1).

- Jude tells us these bad actors are “ungodly persons who turn the grace of our God into indecent behavior and deny our only Master and Lord, Jesus Christ” (Jude 4).

There you have it. A false teacher is someone who denies, disowns, repudiates, or refuses to believe the truth about Jesus. You could say that every heresy, every false teaching, every lie about the gospel always begins by denying something about who Jesus is and what he’s done for his people. People create fake Jesus in their own image.

- People say Jesus never really died.

- That he is not God.

- That he is not eternal.

- That he is not co-equal with the Father.

- That he was not conceived by a miracle of the Holy Spirit in Mary’s womb.

- That he was not sinless.

- That he did not die in our place, as our substitute.

- That his death was not a ransom.

- That his perfect life and willing sacrifice did not satisfy divine justice.

These lies (and others) keep coming back. Every Easter, a major newspaper trots out an article by some liberal scholar who claims to reveal “the truth” about Jesus. False teachers are alive and well. Peter said they would be: “false prophets also appeared among the [old covenant] people, just as there will also be false teachers among you” (2 Pet 2:1).

Q2: How do we know who Jesus is and what he has done?

If a false teacher is someone who denies some key truth about who Jesus is and what he has done, then what tools has God given us so that we can find out these truths? Very simple—by his message, recorded in the bible, and by the Holy Spirit.

Peter tells us about that, too. He wants us to know, with sure conviction, that we can trust the account he’s given us. He and the other disciples didn’t follow clever fables when they told everyone about Jesus—they literally saw him in his majestic splendor (2 Pet 1:16)! They saw what happened to him on that mountain, when he transformed before them into a figure of blazing white, radiant with pure holiness and heavenly light. Peter heard the Father speak words of affirmation about his eternal Son from the heavenly cloud of glory that surrounded them on that mountaintop (2 Pet 1:17-18).

So, he reminds us, the prophecies from the old covenant have now been made surer and more certain. Events have confirmed them. These prophesies and promises are like a lamp shining in a dark place, guiding us until that day when Jesus returns to be the literal light of the world (2 Pet 1:19). So, know this first of all, Peter says: these prophesies weren’t private intuitions or ramblings people made up—they were messages given by men as they were moved by the Holy Spirit to speak (2 Pet 1:20-21)!

The scripture is the record of God’s message to us, and that message is all about Jesus. The Holy Spirit is the who confirms and interprets the scripture for us—every Christian should read John Calvin’s short explanation of this (see Book 1, ch. 7, from Calvin’s Institutes of the Christian Religion). So, to know the truth about Jesus, we must read about his message in the holy scriptures and trust the Spirit of God to help us understand it all.

Q3: How can I be sure I’m interpreting the scriptures about Jesus the right way?

This immediately raises another important question—how do I know that I (and my church) are putting the puzzle pieces together correctly? How do we know we’re believing the right things about Jesus? How do I know I’m interpreting the scriptures the proper way?

Here is where we must deliberately leave our American individualism behind, and make sure we’re on the same page as the untold millions of our Christian brothers and sisters who have gone before us. Jesus tells us that true believers will hear his voice and follow him (Jn 10:1-4). This means that Christians down the centuries have heard the message of the true Jesus, have followed him, and have written down Spirit-led facts and summaries about what the bible says about the true Jesus.

We find this broad consensus about Christian doctrine in the great creeds and confessions of the early church. This doesn’t mean these documents stand atop holy scripture like an infallible filter. One Baptist scholar memorably said we ought to believe in suprema scriptura, which means the bible is the highest or supreme channel of religious authority.1 This is good—we believe that “the Holy Scripture is the only sufficient, certain, and infallible rule of all saving knowledge, faith, and obedience …” (2LBCF, 1.1). So, creeds and confessions aren’t filters that interpret the bible for us—but they are guardrails that give us assurance that we haven’t run off the road and into a ditch.

I’m thinking especially of these documents:

- The Nicene Creed of 325 A.D. and the Nicene-Constantinople Creed of 381 A.D. These clarified Jesus’ deity and his relationship to the Father. Is Jesus a created being? Is Jesus an angel? If Jesus is God’s “son,” then does this mean he came on the scene later than the Father? If Jesus is God, and the Father is God—are Father and Son one being/substance or two?

- The Chalcedonian Creed of 451 A.D. What does it mean that Jesus is both divine and human? Did he stop being divine? Or was he not really a fully human person? What happened to him in the incarnation?

From there, see especially the major creedal documents that give shape to your Christian tradition. Assuming you’re a Protestant Christian, the buffet line goes a bit like this:

- Lutherans have the Book of Concord, which consists of the Augsburg Confession, Luther’s small and large catechisms, and some other documents.

- Presbyterians have the Westminster Standards, which include the Westminster Confession of Faith, and the Westminster larger and smaller catechisms.

- The Reformed have the Three Forms of Unity, which are the Belgic Confession, the Heidelberg catechism, and the Canons of Dort.

- Baptists are cantankerous in this regard, so I’ll just select one strand of the Baptist tradition and suggest the Second London Baptist Confession (“2LBCF”) and the Orthodox Catechism.2

I don’t care which flavor of Christian you are—go to your tradition’s confession of faith and read what it says about Jesus. No matter which tradition you consult from my list, they all say the same thing about Jesus—the same truths, the same affirmations, the same Jesus. Read the 2LBCF’s explanation here—it’s not long!

Why do creeds and confessions matter? Why are they good guardrails?

Because we don’t need to reinvent the wheel every generation. God gave the same Holy Spirit to our brothers and sisters in 325 A.D. as he does today. He led them into all truth, too. They believed the gospel, read the scriptures, learned from their church leaders and from one another, and had power on high from the Spirit of God. They wrote down summary statements of the faith. We have what they wrote. We would be fools to toss all that aside and start fresh with a blank sheet of paper.

This means that, if you and your church believe something about Jesus that no credible group has ever believed in the history of the church … then you’re probably wrong. We can consult a record of sorts because we have those creeds and confessions from centuries gone by that tell us what our brothers and sisters in Christ thought about who Jesus is and what he’s done.

How do we avoid false teachers?

They’re tricksy. They don’t wear orange jumpsuits. They preach false things about who Jesus is and what he’s done—they deny the real Jesus. So, we must read the scripture and trust the Holy Spirit to guide us. We make sure we’re on the right track by joining a local church which swims in the broad stream of Christianity that has existed from the beginning—one that doesn’t naively try to re-invent the wheel but appreciates the guardrails of the tradition of which it is a part.

Peter said to: “remember the words spoken beforehand by the holy prophets and the commandment of the Lord and Savior spoken by your apostles” (2 Pet 3:2). We give ourselves assurance that we’re interpreting the prophecies and our Savior’s words the right way if we make sure we’re not contradicting what our brothers and sisters have said for centuries!

Read your tradition’s governing documents. See what they say about Jesus—again, read the 2LBCF’s summary about him here. If your church proclaims no tradition beyond its own statement of faith or that of a niche movement with no meaningful roots in the broad Christian tradition, then you are likely at greater risk of bring tricked by false teachers.

[1] James L. Garrett, Systematic Theology: Biblical, Historical, and Evangelical, Fourth Edition, vol. 1 (Eugene: Wipf & Stock, 2014), 206.

[2] If you want to read a good, short, and learned explanation of the Baptist tradition, see Matthew Y. Emerson and R. Lucas Stamps, The Baptist Vision: Faith and Practice for a Believer’s Church (Nashville: B&H Academic, 2025).

Listening to the Real Jesus: Insights from the Transfiguration

The story of the transfiguration is one of the most remarkable in the gospels, yet its message is pretty simple: listen to Jesus! If you call yourself a Christian, you might think, “Well, of course! That’s obvious.” But listening to Jesus is harder than we admit. Too often, we listen to a fake version of Jesus that we’ve invented—a Jesus shaped by our own preferences, desires, or cultural influences.

A relationship with God begins with love. We love Him because He first loved us. From this love flows our desire to obey him, believe rightly, and do what his Word says. But what happens if we love the wrong Jesus? Well, if we follow a Jesus of our own making instead of the one revealed in scripture, our beliefs and actions will be all wrong. That’s why it’s important to listen to the real Jesus—the Jesus who is the Son of God, not the one we or our culture have reshaped to fit our own ideals.

Why the transfiguration?

When we read what happened in the run-up to the transfiguration, we learn that it was meant to cement Jesus’ claim to absolute authority in his people’s lives. It’s as if he’s saying: “You gotta listen to me! Not well-meaning but false teachers. Not your culture. Me. I’m kind of a big deal …”

This run-up shows us Jesus having an escalating authority controversy with scribes and Pharisees everywhere he goes. The disciples see and hear all this. For sake of space, we’ll parachute into Matthew 15, where Jesus tells some Pharisees and scribes that they’re hypocrites for emphasizing purity traditions over scripture: “These people honor me with their lips, but their hearts are far from me” (Mt 15:8, quoting Isa 29:13). Jesus then privately compared them to invasive weeds his Father had not planted—the day would come when they’d be ripped out of the ground (Mt 15:13-14; cp. Mt 13:24-30, 36-43)!

We then follow Jesus as he speaks to a Canaanite woman who asks him to cast a demon out of her daughter. She calls him Lord. She recognizes him as the son of David—implicitly, as the king of Israel. He commends her faith (Mt 15:28), a huge irony because she (a non-Jewish person) should have trouble embracing the Jewish Messiah!

Jesus then miraculously feeds 4,000 people in the wilderness east of the Sea of Galilee—people who see his miracles and praise the God of Israel. These are probably not Jewish people (Mt 15:29-31; cp. Mk 7:31)! Matthew now immediately pivots to another confrontation with Jewish authorities who demand he prove his credentials by showing them a sign from heaven (Mt 16:1-4). After telling them off, Jesus warns his followers against the teaching (“the yeast”) of the scribes and Pharisees, whose doctrinal errors are like arsenic for the soul (Mt 16:5, 12).

It’s no accident that Matthew next shows us Jesus asking who people thought he was. Peter answered correctly (“You are the Messiah, the Son of the living God,” Mt 16:16), but was it an intellectual answer or a deeply held conviction? Was it a well-intentioned theory or a heart-felt reality? What did they think of these repeated authority clashes? Do they truly believe that Jesus is their authority?

These implicit questions are what the transfiguration was meant to answer.

What does the transfiguration mean?

The transfiguration tells us who Jesus truly is. They go up the mountain. Suddenly, without warning, Jesus is “transfigured” or “transformed” before their very eyes. It happens suddenly, surprisingly. Jesus’ face shines like the sun, his clothes a dazzling white. This is a terrifying metamorphosis! Moses and Elijah, representing the Law and the Prophets, suddenly appear with him, emphasizing Jesus’ fulfillment and embodiment of both (Mt 17:1-3). But the most striking moment comes when a bright cloud overshadows them, and God the Father speaks: “This is my Son, whom I love; with Him I am well pleased. Listen to Him!” (Mt 17:5).

God is saying: “Do what he says! Keep doing what he says! He is your authority. Hear him!”

Why does this matter? Because when we fail to listen to Jesus, we start listening to competing voices—false teachers, cultural narratives, or even our own misguided emotions. The transfiguration was God’s way of making it abundantly clear: Jesus is the one to whom we should listen above all else.

Why Do People Believe in Fake Jesuses?

Throughout history, people have reshaped Jesus to suit their own agendas. Sometimes this is done with good intentions, but the result is always a distortion of the truth. In Jesus’ day, culture had so re-shaped expectations that many expected a “legalistic Messiah.” In America, in the ante-bellum South, some Christians argued that chattel slavery was a good thing because God was using it as a means of evangelism to enslaved black people! Culture makes us create fakes Jesuses like playdough. It’s no accident that these fake Jesuses always follow whatever culture war battles happen to be raging at the time.

Here are a few modern examples of “fake Jesuses” that people often follow:

- The homosexual Jesus – The lie that says Jesus has cast aside God’s laws about sexual ethics, and that unrepentant homosexual activity is just fine for Christians.

- The transgender Jesus – The lie that says your body can be at odds with your soul—as if your “inner self” can be divorced from your physical body and its gender. We are a unity of body + soul, which is why the doctrine of bodily resurrection is key to the Christian story. You will be resurrected in the physical body with which you were born. There is no legitimate disconnect between your “inner self” and your body.

- The Nationalistic Jesus – Many in America have intertwined faith with patriotism, as if Jesus’ mission were to uphold America’s greatness instead of establishing His Kingdom.

- The Social Justice-Only Jesus – While Jesus absolutely cares about justice, some reduce him to merely a social activist, ignoring his central message of salvation and repentance.

You can go out today and find false churches that teach and promote each of these fake Jesuses. They’re all lies. They’re each a distortion, and when we follow them, we stop truly listening to the real Jesus. The real Jesus, as revealed in scripture, calls us to deny ourselves, take up our cross, and follow Him (Matthew 16:24). That means (among other things) surrendering our own ideas about who he should be and allowing his Word to shape our understanding.

Listening to Jesus in Everyday Life

So how do we practically listen to Jesus? It’s not just about avoiding theological errors—it’s about daily obedience in both big and small ways. Here are a few examples of what it looks like to truly listen to Jesus:

- Caring for the sick and elderly – Choosing to honor and care for aging parents instead of neglecting them.

- Being a faithful spouse – Responding to difficulties in marriage with love and forgiveness rather than bitterness.

- Serving others in your local church – Helping brothers and sisters in need in your church, even when it’s inconvenient.

Jesus is not a coffee table book

What happens when we don’t listen to the real Jesus? History and personal experience show us that failing to heed his voice leads to confusion, division, and spiritual decay. When we shape Jesus in our own image, we end up walking paths that lead us further from God, not closer to him. Even well-meaning people can fall into the trap of creating a fake version of Jesus that fits their lifestyle rather than allowing the real Jesus to transform their life. The apostle Paul tells us this is an evil age (Gal 1:3-4). The apostle John likens this ruined world, with its corrupt and seductive values, to Babylon–and tells it’s all going down one day (Rev 16-19). This world’s “truth” is, in fact, a pack of lies. Jesus tells us to listen to him.

For too many Christians, Jesus is like a decorative coffee table book—nice to have around, but not something they actually engage with. The transfiguration challenges us to move beyond a passive relationship with Jesus. He’s not just a figure to admire; He’s the King of our lives. If we truly listen to Him, it will shape how we think, believe, and live.

As we reflect on the Transfiguration, let’s take God’s words to heart: Listen to him. Not to the competing voices of culture, not to our own desires, but to the true Jesus who reveals himself in Scripture. Only by listening to him can we be transformed and live out the faith we profess.

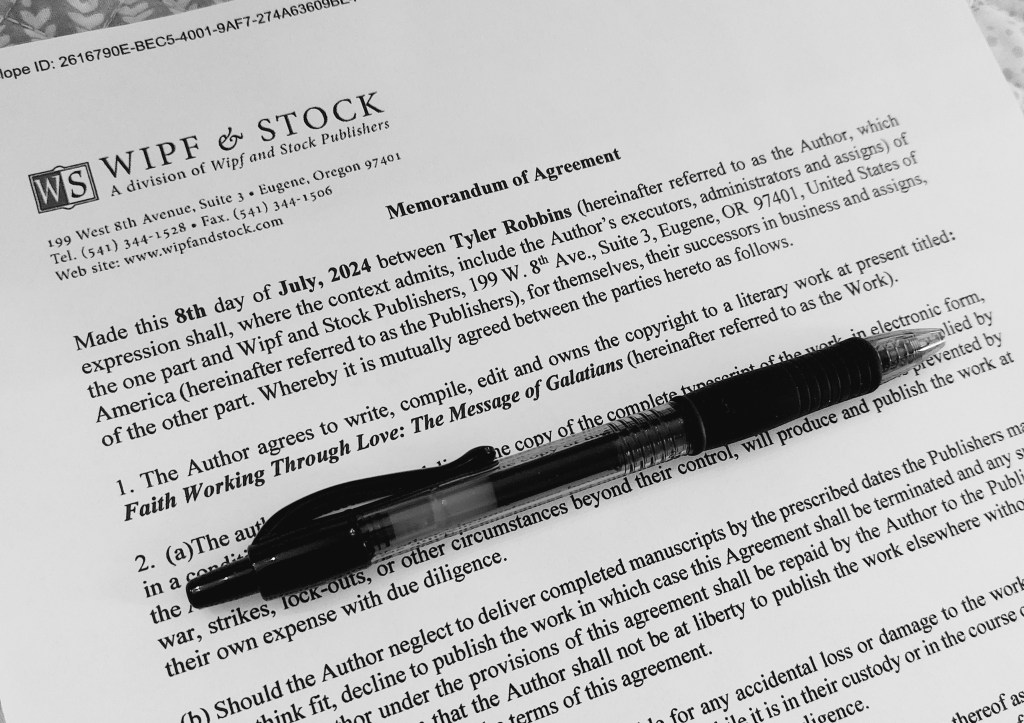

Do you want to review my book?

Wipf & Stock is going to publish a commentary I wrote on the New Testament letter to the Galatians. If you want to be on a list to maybe receive a review copy of the book, then let me know by filling out this form!

The commentary is written for normal people who want to know what Paul is saying. There are no Greek words. There are no long paragraphs about what this scholar says v. what that scholar says. There are no rabbit-trails into questions that theologians like to ponder, but about which ordinary people don’t care and don’t need to know (e.g., did Paul write to Christians in north or south Galatia?). I keep all that stuff in the footnotes. In the text, there is only a straightforward explanation of what Paul says, as best as I understand it.

The commentary will probably end up being about 275 pages. Here is my elevator pitch for why the commentary matters:

How can people be made right with God? The book of Galatians explains. What is the absolute wrong way to try to get right with God? The book of Galatians will explain that, too. What is a real relationship with God supposed to be about? What did Jesus Christ do for us that’s so special and why does it matter to Christians so much? Why does Jesus matter? The book of Galatians talks about all of this. People have always been confused about these questions—even in those first decades of Christianity. The book of Galatians sets us straight, and asks us to trust Jesus and His message.

Here’s the form to be on the list for a review copy.

What is the New Perspective(s) on Paul?

The “New Perspective on Paul” (“NPP”) is a re-calibration of the traditional Protestant understanding of “justification.” NPP has now been a force in New Testament and Pauline scholarship for nearly three generations. This article aims to present a positive statement of NPP. It is a summary, not a critique—so there will be no critical interaction.

First, we briefly sum up the traditional Protestant understanding of “justification.” Next, we survey five aspects of the NPP that differ from the traditional framework.

The Traditional Protestant Understanding of Justification

In light of the New Testament revelation, “justification is God’s declarative act by which, on the basis of the sufficiency of Christ’s atoning death, he pronounces believers to have fulfilled all of the requirements of the law that pertain to them.”[1] The person “has been restored to a state of righteousness on the basis of belief and trust in the work of Christ rather than on the basis of one’s own accomplishment.”[2]

God reckons or imputes Christ’s righteousness to the believer as a judicial declaration—communicating His righteousness to us “by some wonderous way,” transfusing its power into us.[3] For God to “justify” someone means “to acquit from the charge of guilt.”[4] This He does “not as a creditor and a private person, but as a ruler and Judge giving sentence concerning us at his bar.”[5]

One Baptist catechism explains that God “does freely endow me the righteousness of Christ, that I come not at any time into judgment.”[6] Millard Erickson writes: “it is not an actual infusing of holiness into the individual. It is a matter of declaring the person righteous, as a judge does in acquitting the accused.”[7] Union with Christ makes this possible in what Francis Turretin styled a “mystical … communion of grace by mediation. By this, having been made by God a surety for us and given to us for a head, he can communicate to us his righteousness and all his benefits.”[8]

The Baptist, 1833 New Hampshire Confession explains that justification:[9]

- Includes the pardon of sin, and the promise of eternal life on principles of righteousness;

- that it is bestowed, not in consideration of any works of righteousness which we have done, but solely through faith in the Redeemer’s blood;

- by virtue of which faith his perfect righteousness is freely imputed to us of God;

- that it brings us into a state of most blessed peace and favor with God, and secures every other blessing needful for time and eternity.

John Calvin explains that “being sanctified by his Spirit, we aspire to integrity and purity of life.”[10] In other words, good works are the fruit of salvation. Thomas Oden summarizes: “Justification’s nature is God’s pardon, its condition is faith, its ground is the righteousness of God, and its fruits are good works.”[11]

A Survey of Five Aspects of the New Perspective(s) on Paul

There is no single “new perspective,” and it is a mistake to assume that (say) N.T. Wright and James D.G. Dunn speak with one voice on NPP. What unites the new perspective isn’t so much a single consensus on Paul, but more a shared understanding of first-century Judaism.[12] “There is no such thing as the new perspective … There is only a disparate family of perspectives, some with more, some with less family likeness, and with fierce squabbles and sibling rivalries going on inside.”[13]

The NPP is not “new” because it displaces the “old” perspective. “Rather, it is ‘new’ because the dimension of Paul’s teaching that it highlights has been largely lost to sight in more contemporary expositions … The ‘new perspective’ simply asks whether all the factors that make up Paul’s doctrine have been adequately appreciated and articulated in the traditional reformulations of the doctrine.”[14] Dunn explains that the new perspective “is not opposed to the classic Reformed doctrine of justification. It simply observes that a social and ethnic dimension was part of the doctrine from its first formulation …”[15]

We will survey the NPP by looking at five related issues:[16]

- The new perspective on Paul arises from a new perspective on Judaism.

- The significance of Paul’s mission is the context for his teaching on justification.

- What does Paul mean when he writes about justification by faith in Christ Jesus and not works of the law?

- What does “justification” mean?

- What is the relationship between works and salvation?

The new perspective on Paul arises from a new perspective on Judaism

Judaism was not a religion of works-righteousness, but of grace. The Reformed (or “Lutheran”) perspective errs by reading the Protestant-Catholic divide back into Paul’s polemics in Galatians and Romans. “The degeneracy of a Catholicism that offered forgiveness of sins by the buying of indulgences mirrored for Luther the degeneracy of a Judaism that taught justification by works.”[17]

The NPP objects to this framework. Instead, it sees a “symbiotic relationship implicit in Israel’s religion (and Judaism) between divine initiative and human response.”[18] Israel’s obedience to the law was not about amassing good works to wipe away sin—it was simply a response to God’s covenant faithfulness.

E.P. Sanders coined the term “covenantal nomism” to describe this ethos and said it was “the view that one’s place in God’s plan is established on the basis of the covenant and that the covenant requires as the proper response of man his obedience to its commandments, while providing means of atonement for transgression.”[19]

The “righteousness of God” was saving righteousness, not judgment. Luther came to realize this, but Dunn writes that “it wasn’t a new insight for the bulk of Second Temple Judaism; it was rather an axiom that was fundamental to Judaism itself.”[20] Dunn asks whether “traditional Christian antipathy to Judaism has skewed and distorted its portrayal of the Judaism against which Paul reacted?”[21]

So, it is a mistake to read Paul as if he were reacting against crude legalism. Indeed, Paul’s “zeal for God” (Phil 3:6) was “not simply zeal to be the best that he could be,” but a zeal to attack Jews who were violating these boundary markers and thus being unfaithful to the covenant they did not realize was now obsolete.[22] Paul did not attack legalism—he attacked a now-outmoded Jewish nationalism.

The significance of Paul’s mission is the context for his teaching on justification

Paul’s great burden was to proclaim that God’s community included both Jew and Gentile—and this was unacceptable to the Judaism of his day. The Torah taught the Israelites to be different, to be set apart. Dunn says, “no passage makes this clearer than Lev 20.22-26,” which reads (in part): “You must not live according to the customs of the nations I am going to drive out before you,” (Lev 20:23).

So, Dunn argues, this “set-apartness” ethic is what motivated the agitators we read about in Galatians. It is this clash which is “evidently the theological rationale behind Peter’s ‘separation’ from the Gentiles of Antioch.”[23]

Judaism was not missionary minded. Why should it? Judaism was primarily an ethnic religion, the religion of the residents of Judea, that is, Judeans. So it was natural for Second Temple Jews to think of Judaism as only for Jews, and for non-Jews who became Jews. This was where Christianity, initially a Jewish sect, broke the established mold. It became an evangelistic sect, a missionary movement, something untoward, unheard of within Judaism.[24]

Even Jewish Christians found it difficult to fathom the Gospel going to Gentiles (see Peter at Cornelius’ home in Acts 10:27-29, 44-48). This conflict—the “who is a child of God and therefore what is required to become one?” question—drove his teaching on justification. “The social dimension of the doctrine of justification was as integral to its initial formulation as any other … A doctrine of justification by faith that does not give prominence to Paul’s concern to bring Jew and Gentile together is not true to Paul’s doctrine.”[25]

For the new perspective, the concern that Paul’s concept of justification by faith addresses is not a universal human self-righteousness instantiated in a Pelagian-like, works driven Judaism. Rather, it is a problem specific to the setting of the early church, where a dominant (Jewish) majority was attempting to force the Gentile minority into adopting the Torah-based symbols of the (Jewish) people of God in order to gain access to the (Jewish) Messiah Jesus. As such, Paul’s teaching on justification is nothing like the “center” of his theology—let alone the “article by which the Church stands or falls.”[26]

What does Paul mean when he writes about “justification by faith” in Christ Jesus and not “works of the law”?

“But, if Judaism was essentially a religion of grace, then why did Paul reject it?”[27] That is the question! To what was Paul objecting when he railed against “works of the law?”

Well, because Judaism was a religion of grace, this means legalism is not the true issue, and we are mis-reading Paul if we think it is. Because the “works of the law” are not about legalism, they must be about something else—but what? Well, the cultural wall against which Paul kept hitting his head was about whether Gentiles could come into God’s family, and what this “coming in” looked like.

The Jewish agitators believed the “coming in” meant observing certain Jewish “boundary markers” like circumcision, the Sabbath, and the laws about cleanness and uncleanness—that is, becoming Jews. God gave them to keep His people separate from the world. Dunn explains “works of the law” also included “the distinctively Jewish way of life”[28]—a sort of sociological identity to which the boundary markers pointed.

But Jesus has now come and fulfilled these good but temporary boundary markers. They no longer tag someone as “in” or “out” of the covenant—faith in Christ and indwelling of the Spirit is now the boundary marker. This is the dividing line. This is what Paul meant when he spoke against “works of the law.”

Paul taught and defended the principle of justification by faith (alone) because he saw that fundamental gospel principle to be threatened by Jewish believers maintaining that as believers in Messiah Jesus, they had a continuing obligation to maintain their separateness to God, a holiness that depended on their being distinct from other nations, an obligation, in other words, to maintain the law’s requirement of separation from non-Jews … For Paul, the truth of the gospel was demonstrated by the breaking down of the boundary markers and the wall that divided Jew from Gentile, a conviction that remained the central part of his mission precisely because it was such a fundamental expression of, and test case for, the gospel. This is the missing dimension of Paul’s doctrine of justification that the new perspective has brought back to the center of the stage where Paul himself placed it.[29]

What does “justification” mean?

Dunn explains that “justification by faith” means trusting in Jesus alone for salvation, and not relying on obsolete Jewish boundary markers as covenant preconditions for God’s acceptance (i.e., “works of the law”). Jesus is enough. According to Dunn, Paul’s target is not grace v. legalism, but grace v. outmoded nationalism.

N.T. Wright explains that righteousness is not a changed moral character, but a new declared status—acquittal.[30] The true scene is the lawcourt, not a medical clinic.[31]

It is the status of the person which is transformed by the action of “justification,” not the character. It is in this sense that “justification” “makes” someone “righteous,” just as the officiant at a wedding service might be said to “make” the couple husband and wife-a change of status, accompanied (it is hoped) by a steady transformation formation of the heart, but a real change of status even if both parties are entering the union out of pure convenience.[32]

He breaks decisively with the traditional perspective by saying that “righteousness” is not a substance which can imputed or reckoned to a believer.[33] This is dangerously close to the Roman Catholic concept of righteousness as an infusion of grace.[34] No, Wright argues, God is not “a distant bank manager, scrutinizing credit and debit sheets.”[35] Christ has not amassed a “treasury of merit” that God dispenses to believers.[36]

But “righteousness as declared status from God” is not the whole story. Wright sets his NPP framework by insisting we read all of scripture through a “God’s single plan through Israel for the world” lens. This means “righteousness” is more than acquittal, because this declared status takes place in a particular context. It is “absolutely central for Paul” that one understand “the story of Israel, and of the whole world, as a single continuous narrative which, having reached its climax in Jesus the Messiah, was now developing in the fresh ways which God the Creator, the Lord of history, had always intended.”[37]

For Wright, this is the hinge upon which everything turns. “Paul’s view of God’s purpose is that God, the creator, called Abraham so that through his family he, God, could rescue the world from its plight.”[38] He sums up this “single-plan-through-Israel-for-the-world” hinge as “covenant.”[39]

This is the prism through which we must understand (a) the nature of the law and the believing life, (b) what “works of the law” meant to Paul, and (c) the apostle’s relentless focus on the Jew + Gentile family of God.

In Paul’s day, Wright notes, Jews were not sitting around wondering what they must do to get to heaven when they die. No—they were waiting for God to act just as He said He would (i.e., to show covenant faithfulness), because they counted on being part of His single-plan-through-Israel-for-the-world.[40] They were in “exile,” and waiting for a Savior who would be faithful to God’s promises to them.[41]

The Gospel is not simply about us and our salvation. It is about God’s plan. “God is not circling around us. We are circling around him.”[42] We are making a mistake, Wright says, if we make justification the focus of the Gospel. The steering wheel on a car is surely important (critical, even!), but it is not the whole vehicle.[43] In the same way, justification is one vital component of a larger whole—God’s “single-plan-through-Israel-for-the-world” plan.

God had a single plan all along through which he intended to rescue the world and the human race, and that this single plan was centered upon the call of Israel, a call which Paul saw coming to fruition in Israel’s representative, the Messiah. Read Paul like this, and you can keep all the jigsaw pieces on the table.[44]

Because the Christian story hinges upon this covenant, Wright interprets the “righteousness of God” as God’s covenant faithfulness to do what He promised for Abraham. This faithfulness consisted of three aspects: (a) eschatology—God’s “single-plan-through-Israel-for-the-world” unfolding in time, and (b) lawcourt, and (c) covenant.

Paul believed, in short, that what Israel had longed for God to do for it and for the world, God had done for Jesus, bringing him through death and into the life of the age to come. Eschatology: the new world had been inaugurated! Covenant: God’s promises to Abraham had been fulfilled! Lawcourt: Jesus had been vindicated-and so all those who belonged to Jesus were vindicated as well! And these, for Paul, were not three, but one. Welcome to Paul’s doctrine of justification, rooted in the single scriptural narrative as he read it, reaching out to the waiting world.[45]

What is the relationship between works and salvation?

Paul declares that it is “the doers of the law who will be justified” (Rom 2:13), and that God will repay each person for what he has done (Rom 2:6). Jesus is the judge at the law-court, and “possession of Torah, as we just saw, will not be enough; it will be doing it that counts …”[46]

Wright says traditional interpretations of these passages have “swept aside” the implications of Paul’s words. Judgment is—somehow, someway—based on works. It is “a central statement of something [Paul] normally took for granted. It is base line stuff.”[47]

This “judgment” is not a reward ceremony for believers where some will get prizes and others will not. No, it is an actual judgment at which everyone (including but not limited to Christians justified by faith) must present themselves and be assessed.[48] To critics who are alarmed at Wright’s insistence on this point, he replies: “I did not write Romans 2; Paul did.”[49] Indeed, “those texts about final judgment according to works sit there stubbornly, and won’t go away.”[50]

Christians are to “do” things to please God. Joyfully, out of love. To those who accuse him of teaching believers to put their trust in something other than Jesus, Wright declares: “I want to plead guilty …”[51]

The key, Wright argues, is the Holy Spirit who sets us free from slavery and for responsibility—“being able at last to choose, to exercise moral muscle, knowing both that one is doing it oneself and that the Spirit is at work within, that God himself is doing that which I too am doing.”[52] The believer “by persistence in doing good” seeks glory and honor and immortality (Rom 2:7). It is not a matter of earning the final verdict or ever arriving at perfection. “They are seeking it, not earning it.”[53]

This seeking is by means of Spirit-filled living that is a bit of a synergistic paradox—“from one point of view the Spirit is at work, producing these fruits (Galatians 5:22-23), and from another other point of view the person concerned is making the free choices, the increasingly free (because increasingly less constrained by the sinful habits of mind and body) decisions to live a genuinely, fully human life which brings pleasure—of course it does!—to the God in whose image we human beings were made.”[54]

This is the kind of life which leads to a positive final verdict.[55]

The present verdict gives the assurance that the future verdict will match it; the Spirit gives the power through which that future verdict, when given, will be seen to be in accordance with the life that the believer has then lived.[56]

Both Sanders and Dunn are more to the point and suggest Christianity is kinda, sorta a new flavor of covenantal nomism. Dunn writes that the Torah was both the way of life and the way to life, that we cannot play the two emphases off against one another, and that “NT teaching has the same or at least a very similar inter-relationship.”[57]

As Israel’s status before God was rooted in God’s covenant initiative, so for Paul, Christians’ status before God is rooted in the grace manifested in and through Christ. And as Israel’s continuation within that covenant relationship depended in substantial measure on Israel’s obedience of the covenant law, so for Paul the Christians’ continuation to the end depends on their continuing in faith and on living out their faith through love.[58]

The difference is that the New Covenant believer has the Spirit, and so the Christian must walk by the Spirit and “to fulfill the requirements of the law.”[59] Sanders sees Paul as more transforming old categories than dressing them in new clothes. The apostle uses “participationist transfers terms” to describe his doctrine of salvation:

The heart of Paul’s thought is not that one ratifies and agrees to a covenant offered by God, becoming a member of a group with a covenantal relation with God and remaining in it on the condition of proper behaviour; but that one dies with Christ, obtaining new life and the initial transformation which leads to the resurrection and ultimate transformation, that one is a member of the body of Christ and one Spirit with him, and that one remains so unless one breaks the participatory union by forming another.[60]

If you break the union (by defecting and not repenting), then you are out—“good deeds are the condition of remaining ‘in’, but they do not earn salvation.”[61]

What does it matter?

This matters because the NPP will interpret Galatians and Romans quite differently.

- Judaism is a religion of grace, forgiveness, and atonement—not of legalism.

- This means Paul is not fighting against legalists. Luther and the Reformers are wrong on this point. So is every major creed and confession the Protestant world has produced in the past 400 years. Like people staring up at the sun and assuming it orbits the earth, the traditional perspective sees but does not understand.[62]

- Paul’s real problem is a mis-guided Jewish nationalism its agitators do not realize is now obsolete.

- So, the “works of the law” Paul rails against are not legalist impulses but Jewish “identity markers.” Being a covenant member means an obligation to be set apart and to “live Jewishly.” The agitators do not realize this is now superseded in union with Christ. So, in this context, “justification by faith” means observing Jesus and the indwelling of the Spirit as the new boundary markers.

- The traditional understanding of “justification” is wrong. It may mean observing these new boundary markers instead of the old (Dunn). Or, according to Wright, it might mean “covenant faithfulness,” in that God is bringing His “single-plan-through-Israel-for-the-world” to fruition (eschatology), on the basis of His declaration that Jesus acquits His people of their legal guilt (lawcourt), because He made promises to Abraham He intends to fulfill (covenant).

This alternative grid produces quite different interpretations of seemingly “obvious” passages. For example, the apostle Paul writes this about ethnic Jewish people:

For I can testify about them that they are zealous for God, but their zeal is not based on knowledge. Since they did not know the righteousness of God and sought to establish their own, they did not submit to God’s righteousness (Romans 10:2-3).

According to N.T. Wright, this “zeal … not based on knowledge” refers to the mistaken impression that Israel was not the center of the world. God intended to work not just for them, but through them for a greater plan for the world. As far as “establishing their own righteousness” goes, Paul means that “they have not recognized the nature, shape and purpose of their own controlling narrative … and have supposed that it was a story about themselves rather than about the Creator and the cosmos, with themselves playing the crucial, linchpin role.”[63]

In other words, these passages are about misguided Jewish nationalism, not legalism. Christians (especially pastors) should be familiar with the broad outlines of this newer interpretive grid. Pondering these challenges will both sharpen dull edges in our own understanding and strengthen convictions in the face of alternative challenges. It might even change some minds—the Spirit still has more to teach His church!

[1] Millard Erickson, Christian Theology, 3rd (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2013), p. 884.

[2] Millard Erickson, The Concise Dictionary of Christian Theology, revised ed. (Wheaton: Crossway, 2001), s.v. “justification by faith,” p. 108

[3] John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, trans. Henry Beveridge (reprint; Peabody: Hendriksen, 2012), 3.11.23

[4] Calvin, Institutes, 3.11.3.

[5] Francis Turretin, Institutes of Elenctic Theology, ed. James T. Dennison Jr., trans. George Musgrave Giger, vol. 2 (Phillipsburg: P&R Publishing, 1992–1997), 16.3.2.

[6] Hercules Collins, An Orthodox Catechism: Being the Sum of Christian Religion, Contained in the Law and Gospel, ed(s). Machael Haykin and G. Stephen Weaver, Jr. (Palmdale: RBAP, 2014), A55.

[7] Erickson, Christian Theology, p. 884.

[8] Turretin, Institutes, 16.3.5.

[9] 1833 New Hampshire Confession of Faith, Art. V, quoted in Phillip Schaff, Creeds of Christendom, vol. 3 (New York: Harper & Bros., 1882), pp. 743-744.

[10] Calvin, Institutes, 3.11.1.

[11] Thomas Oden, Classical Christianity: A Systematic Theology (San Francisco: HarperOne, 2009), p. 584.

[12] James K. Bielby and Paul R. Eddy, “Justification in Contemporary Debate,” in Justification: Five Views (Downers Grove: IVP, 2011), p. 57.

[13] N.T. Wright, Justification: God’s Plan & Paul’s Vision (Downers Grove: IVP, 2009), loc. 233-234.

[14] James D. G. Dunn, “New Perspective View,” in Justification: Five Views, pp. 176, 177.

[15] Dunn, “The New Perspective on Paul: Whence, what and whither?” in The New Perspective on Paul, revised ed. (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2005),p. 36.

[16] Three of these issues are from Dunn, “New Perspective View,” p. 177.

[17] Dunn, “New Perspective View,” p. 180.

[18] Dunn, “New Perspective View,” p. 181.

[19] E.P. Sanders, Paul and Palestinian Judaism, 40th anniversary ed. (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2017), p. 75.

[20] Dunn, “New Perspective View,” p. 182.

[21] Dunn, “New Perspective View,” pp. 182-183.

[22] Dunn, “Whence, what and whither?” pp. 12-13.

[23] Dunn, “Whence, what and whither?” pp. 30-31.

[24] Dunn, “New Perspective View,” pp. 186-187.

[25] Dunn, “New Perspective View,” pp. 189.

[26] Bielby and Eddy, “Justification in Contemporary Debate,” in Justification: Five Views, p. 60.

[27] Bielby and Eddy, “Justification in Contemporary Debate,” in Justification: Five Views, p. 58.

[28] Dunn, “Whence, what and whither?,” in New Perspective, pp. 27-28.

[29] Dunn, “New Perspective View,” p. 195.

[30] Wright, Justification, loc. 987.

[31] Wright, Justification, loc. 994.

[32] Wright, Justification, loc. 1002-1005.

[33] “If ‘imputed righteousness’ is so utterly central, so nerve-janglingly vital, so standing-and-falling-church and-falling-church important as John Piper makes out, isn’t it strange that Paul never actually came straight out and said it?” (Wright, Justification, loc. 453-454).

[34] Wright, Justification, loc. 1938.

[35] Wright, Justification, loc. 2216.

[36] Wright, Justification, loc. 2747-2748. “We note in particular that the ‘obedience’ of Christ is not designed to amass a treasury of merit which can then be ‘reckoned’ to the believer, as in some Reformed schemes of thought …”

[37] Wright, Justification, loc. 307-309.

[38] Wright, Justification, loc. 1041-1042.

[39] Wright, Justification, loc. 649f.

[40] Wright, Justification, loc. 546f.

[41] “[M]any first-century Jews thought of themselves as living in a continuing narrative stretching from earliest times, through ancient prophecies, and on toward a climactic moment of deliverance which might come at any moment … this continuing narrative was currently seen, on the basis of Daniel 9, as a long passage through a state of continuing ‘exile’ … The very same attribute of God because of which God was right to punish Israel with the curse of exile—i.e., his righteousness—can now be appealed to for covenantal restoration the other side of punishment,” (Wright, Justification, loc. 601-602, 609, 653-655).

In his Paul and the Faithfulness of God (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2013; Kindle ed.), Wright helpfully explains: “… the covenant, YHWH’s choice of Israel as his people, was aimed not simply at Israel itself, but at the wider and larger purposes which this God intended to fulfil through Israel. Israel is God’s servant; and the point of having a servant is not that the servant becomes one’s best friend, though that may happen too, but in order that, through the work of the servant, one may get things done. And what YHWH wants done, it seems, is for his glory to extend throughout the earth, for all nations to see and hear who he is and what he has done …

The particular calling of Israel, according to these passages, would seem to be that through Israel the creator God will bring his sovereign rule to bear on the world. Israel’s specialness would consist of this nation being ‘holy,’ separate from the others, but not merely for its own sake; rather, for the sake of the larger entity, the rest of the world,” (pp. 804-805, emphases in original).

[42] Wright, Justification, loc. 163-164.

[43] Wright, Justification, loc. 948f.

[44] Wright, Justification, loc. 326-329.

[45] Wright, Justification, loc. 1131-1134.

[46] Wright, Justification, loc. 2163-2164.

[47] Wright, Justification, loc. 2183-2184.

[48] Wright, Justification, loc. 2174.

[49] Wright, Justification, loc. 2168.

[50] Wright, Justification, loc. 2200-2201.

[51] Wright, Justification, loc. 2220.

[52] Wright, Justification, loc. 2230-2232.

[53] Wright, Justification, loc. 2266.

[54] Wright, Justification, loc. 2267-2270.

[55] “Humans become genuinely human, genuinely free, when the Spirit is at work within them so that they choose to act, and choose to become people who more and more naturally act (that is the point of ‘virtue,’ as long as we realize it is now ‘second nature,’ not primary), in ways which reflect God’s image, which give him pleasure, which bring glory to his name, which do what the law had in mind all along. That is the life that leads to the final verdict, ‘Well done, good and faithful servant!’” (Wright, Justification, loc. 2279-2282).

[56] Wright, Justification, loc. 3058-3060.

[57] Dunn, “Whence, when and whither?,” pp. 74-75.

[58] Dunn, “New Perspective View,” pp. 199-200.

[59] Dunn, “Whence, when and whither?,” pp. 84-85.

[60] Sanders, Paul and Palestinian Judaism, p. 513.

[61] Sanders, Paul and Palestinian Judaism, p. 517.

[62] Wright, Justification, loc. 101-114.

[63] Wright, Justification, loc. 2966-2967.

Jesus is always faithful

This is my translation of 2 Timothy 2:11-14, which is the text I’m using for a memorial service sermon tomorrow. I never use my own translations while preaching, but the act of translating really helps me understand what the passage says. This is a very beautiful passage.

Some teachers believe v. 13 is a warning about the cost of rejecting the Gospel. I disagree–I think it’s an encouraging word about how, even as we fail to be as trustworthy, reliable, and dependable as we ought to be, Jesus is always faithful.

Jim Crow wasn’t inevitable

C. Vann Woodward was a celebrated historian of the American South. His most well-known work is The Strange Career of Jim Crow, originally published in 1955 and updated for the last time in 1974. He aimed to explain why and how, exactly, we went from (1) the end of the Civil War and Reconstruction to (2) a segregation more complete than anything experienced in the antebellum, pre-war South.

His startling thesis was that the Jim Crow laws did not follow immediately on the heels of the Civil War, but came perhaps 30 years later and destroyed the (in some quarters) considerable progress that had been made in race relations. This is known as the “Woodward thesis.” He explains:

The obvious danger in this account of the race policies of Southern conservatives and radicals is one of giving an exaggerated impression of interracial harmony. There were Negrophobes among the radicals as well as among the conservatives, and there were hypocrites and dissemblers in both camps. The politician who flatters to attract votes is a familiar figure in all parties, and the discrepancy between platforms and performance is often as wide as the gap between theory and practice, or the contrast between ethical ideals and everyday conduct.

My only purpose has been to indicate that things have not always been the same in the South. In a time when the Negroes formed a much larger proportion of the population than they did later, when slavery was a live memory in the minds of both races, and when the memory of the hardships and bitterness of Reconstruction was still fresh, the race policies accepted and pursued in the South were sometimes milder than they became later.

The policies of proscription, segregation, and disfranchisement that are often described as the immutable ‘folkways’ of the South, impervious alike to legislative reform and armed intervention, are of a more recent origin.

The effort to justify them as a consequence of Reconstruction and a necessity of the times is embarrassed by the fact that they did not originate in those times. And the belief that they are immutable and unchangeable is not supported by history.

C. Van Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow, 3rd ed. (New York: OUP, 2002; Kindle ed.), 65.

Now, that’s something to chew on. Here’s something more – where were the Christians in the South as this reversion to evil took place?

Note: The feature photograph (above) depicts Sheriff Willis McCall, of Lake County, FL, in November 1951 moments after he murdered one man and shot another during a fake “escape attempt” he staged as he transported both men to a State prison. This case of the so-called “Groveland Four,” in which his department framed four innocent men for the illusory rape of a white woman, is a poster child for the evils of the Jim Crow laws.

My Confession

Augustine has his Confessions (the Pine-Coffin translation is the best), and I have mine.

I like paper reference books. I have both a robust thesaurus and a good, intermediate dictionary near my desk which I often consult. They are:

- Merriam-Webster Collegiate Dictionary, 11th ed.

- Oxford American Writer’s Thesaurus, 3rd ed.

Most people don’t use references like these. If they do, they likely just Google what they want (or, perhaps, Bing it …). I don’t. I use these physical books. A lot. I have an online subscription to the Oxford English Dictionary through one of my seminaries, but I only consult it for deeper matters. For everyday work, I use these two references.

But, I was lamenting recently that my Merriam-Webster is just getting old. The last update was 2003. Now, of course, I can find anything I want online. the collegiate dictionary is updated at Merriam-Webster.com. But, you see, I don’t want to find it online. I want a physical book I can look at, open, and study.

What to do? I have a 2003 dictionary. Merriam-Webster is the last true lexicon left in America. It seemed I had little choice but to soldier on with my trusty Merriam-Webster Collegiate.

Then, it happened. I was looking for something in my thesaurus just today and noticed it was the Oxford American Writer’s Thesaurus.

American.

Then, I remembered that Oxford puts out a New Oxford American Dictionary (now in its 3rd edition). I hadn’t thought about it much, before. Now, I began thinking about it. I looked it up. Published 2010. Perhaps 33% more word entries than the good ‘ole Merriam-Webster. Larger. Newer. Better. It’s content culled from the two-billion word corpus that underlies the entire Oxford English Dictionary.

I decided I must have it. So, I bought it.

What’s my confession? Just that I bought a new dictionary and I’m happy about it.

That is all.

Gems from Augustine

“The truth is that in the mysterious justice of God the wickedness of desire is given rope, as it were, for the present, while its punishment is plainly being reserved for the final judgment,” (City of God, 1.28).

Abortion and the Christian

This past Sunday, I preached perhaps the most depressing sermon of my life, entitled, “What Should a Christian Think About Abortion?” It was depressing to study and prepare for, and even more depressing to deliver. It’s necessary to talk about this topic, because it is act of terrible wickedness. However, God is rich in mercy and grace, and can forgive anyone of any sin – including abortion. That was an important focus of my sermon, as I said here:

Today, both legislative houses in the State of New York passed a bill entitled the “Reproductive Health Act.” You can find a good article on this issue, here. But, the best place to go is the source. And, the excerpt of the new law I want you to see is this:

§ 2599-aa. Policy and purpose. The legislature finds that comprehensive reproductive health care is a fundamental component of every individual’s health, privacy and equality. Therefore, it is the policy of the state that:

The term “reproductive health care” is often a polite euphemism for “abortion.” As you read this new law, think about how the horror of the language’s meaning is clouded by the boring, bureaucratic prose. The law continues:

1. Every individual has the fundamental right to choose or refuse contraception or sterilization.

There is no argument, here. The crux is in what comes next …

2. Every individual who becomes pregnant has the fundamental right to choose to carry the pregnancy to term, to give birth to a child, or to have an abortion, pursuant to this article.

In my sermon, I mentioned there were two principles that formed the philosophical foundation that makes the pro-abortion mindset possible. To be sure, not every woman who has an abortion actually buys into this mindset wholeheartedly. But, I submit these two sinful principles certainly help provide moral justification for the act of abortion.

These principles are: (1) a denial that the unborn child is a “person” with a corresponding right to life, and (2) an insatiable demand for personal autonomy, to deny you’re under the authority of God, your creator.

You can see that with this language. The law declares, without any justification, that every person who becomes pregnant “has the fundamental right … to have an abortion.”

Says who? You can only buy into this idea if you (1) don’t believe the unborn child is a human being with rights, and (2) you’ve wholeheartedly bought the idea that you’re a law unto yourself. Both these ideas are sinful, wrong, and at odds with the Christian faith.

In my sermon, I talked about the why Christians should see human life is sacred, because people are made “in the image of God:”

I then spoke about the Christian definition of “personhood:”

3. The state shall not discriminate against, deny, or interfere with the exercise of the rights set forth in this section in the regulation or provision of benefits, facilities, services or information.

If you deny the statement in #2 (above), then you “discriminate.”

§ 2599-bb. Abortion.

1. A health care practitioner licensed, certified, or authorized under title eight of the education law, acting within his or her lawful scope of practice, may perform an abortion when, according to the practitioner’s reasonable and good faith professional judgment based on the facts of the patient’s case: the patient is within twenty-four weeks from the commencement of pregnancy, or there is an absence of fetal viability, or the abortion is necessary to protect the patient’s life or health.

This law expands who may perform an abortion. Now, in the State of New York, any “health care practitioner” can conduct one. A “health care practitioner” can be a physician, midwife, or even a physician’s assistant.

When can an abortion be done? There are three circumstances:

First, the abortion can be conducted at any time up to 24 weeks (6 months). This up to the cusp of the third trimester. By this time, the baby has unique fingerprints, can grasp things with its hands, can smile, has visible sex organs, has vocal cords, the mother can feel movement, and the baby even has a bit of hair. Babies born at the 24 week mark have survived.

At this point, it’s likely one of these abortion procedures I described on Sunday will be used:

Second, the abortion can be conducted if there is reason to believe the baby will not survive to term.

Third, and this is the most chilling of all, an abortion may be performed if it’s “necessary to protect the patient’s life or health.” Who determines this? As quoted above, it depends “on the practitioner’s reasonable and good faith professional judgment based on the facts of the patient’s case.” This is purposely vague language; you can make this mean whatever you want. Judgment based on what? The law doesn’t say, which means there’s a hole big enough to drive a Mack truck through. This is likely the point.

Here is a video clip from Planned Parenthood, documenting the spontaneous cheers which erupted in the New York legislature when this evil bill passed:

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.jsBREAKING: New York State Senate just made HISTORY and passed the Reproductive Health Act on the anniversary of #RoevWade! pic.twitter.com/u2diMzgSQW

— 📢 PPNYC Action Fund (@PPNYCAction) January 22, 2019

Abortion is a terrible evil that has plagued our land. Christians have a duty to speak out compassionately and forcefully, emphasizing both God’s condemnation of this wicked act, and His mercy, grace, love and kindness to forgive any and everyone who comes to Him in repentance and faith.

Today, one Christian theologian said it best:

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.jsThe American dead in every conflict and war since the American Revolution in 1776: 1,354,664

— Dustin Benge (@DustinBenge) January 22, 2019

The American dead in every abortion since 1973: 61,000,000

How we should weep.

Amen.