We continue our look at the great prophecy of Daniel 9:24-27. Read the rest of the series.

This prophecy wraps up here, in the last bit of Daniel 9:27. It is the antichrist will make a covenant. He is the one to whom Titus Vespasianus—the conqueror and destroyed of Jerusalem in A.D. 70—pointed in Daniel 9:26 (“the people of the prince who is to come”). With whom will antichrist make this covenant and for how long? How does this prophecy end, in light of other scripture passages?

The covenant—with whom and for how long?

Gabriel tells Daniel:

And he will confirm a covenant with the many for one week, but in the middle of the week he will put a stop to sacrifice and grain offering; and on the wing of abominations will come the one who makes desolate, until a complete destruction, one that is decreed, gushes forth on the one who makes desolate (Daniel 9:27).

Who are “the many” with whom this evil ruler will make this covenant? Gabriel does not explain who the “many” are. If you believe the “he” in Daniel 9:27 is Jesus, then “the many” would be believers—members of the new covenant in Christ’s blood. But we’ve seen that this isn’t the best interpretation, so we’ll leave that aside and instead assume the antichrist makes a covenant with … someone. There are two good options:

- Option 1: Because Gabriel told us at the beginning that this prophecy was “for your people and your holy city” (Dan 9:24), we might assume the “many” here are the people of Israel—the nation.[1]

- Option 2: However, another option is that the “many” with whom Antichrist makes a covenant are his followers—that is, the unsaved people who desire (either because of terror or by demonic conviction) to ally themselves to antichrist in a crude imitation of Jesus’ coming kingdom.[2]

Three factors tip the scales in favor of Option 1:

- The angel Gabriel said this prophecy was “for your people and your holy city” (Dan 9:24). This suggests the Israeli people are the focus of the prophecy.

- The antichrist’s actions in Daniel 9:27 seem to be against the people with whom he made a covenant—they are the ones against whom he moves “in the middle of the week.” It makes little sense for the Antichrist to attack and persecute the people who are already on his side.

- Other passages very strongly suggest there will be a period of approximately seven years during which antichrist specifically persecutes Israel (Rev 11, 13). The Book of Revelation paints these events in a dramatically figurative manner with a strong Jewish flavor (see Rev 11:1-8).

So, it seems better to understand the antichrist as making some kind of covenant with the nation of Israel. We do not know what this covenant will be about—whether it will be voluntary or coerced. The covenant may not be voluntary—the word can give the sense of the evil ruler forcing it on the basis of superior strength.[3]

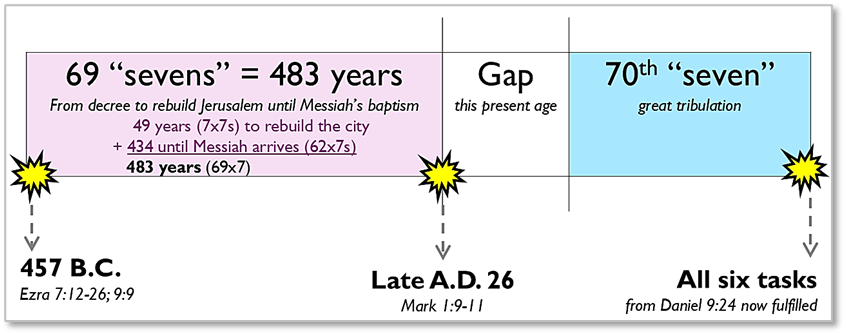

Because we already learned that each “seven” = a unit of seven years, and that the first 69 “sevens” work when interpreted this way, it’s reasonable to believe this 70th “seven” is also one unit of seven years. Remember, this 70th “seven” is the last event in Gabriel’s timeline.

The scriptures often give hints of a terrible calamity during the last days, lasting for approximately seven years.

- Revelation 11:1-13 speaks of two special, powerful witnesses for Jesus who go about Jerusalem for 1,260 days or 42 months (≈ 3.5 years), preaching and doing miracles, before a ferocious, sinister, and evil creature kills them both—the Antichrist, empowered by a “dragon” who represents Satan.

- This antichrist/beast figure then rules in a cruel and evil manner for 42 months (≈ 3.5 years; Rev 13:1-10).

- Combined, this is a total of ≈ seven years, which Daniel hints is characterized by (a) one half (3.5 years) of relative peace but impending danger, and then (b) 3.5 years of abject evil.

In Daniel 9:27, in the midst or middle of this covenant that lasts seven years, we learn “he will put a stop to sacrifice and grain offering.” On face value, this makes no sense—unless there is a temple (complete with a re-launched, old covenant sacrificial system) in Jerusalem at which the antichrist can put a stop to this. Many Christians in America believe it must mean this.[4] If so, there must first occur a series of events so cataclysmic that they seem implausible today:

- The modern state of Israel must completely change its character and become a Jewish nationalist state. This would be a big deal. Modern Israel is a very secular country.

- Israel must expel all Muslim structures and worshippers from the historical site of the temple in Jerusalem. This is almost too fantastic to believe—it would have to be a miracle.

- Israel must have sufficient military and economic resources to pull this off in the face of determined opposition—many, many, many political stars would have to align.

With God, all things are possible. God can do this if he wishes. Many Christians believe he will—this is why so many bible teachers watch Israel and Middle East politics very closely. Unfortunately, some of these teachers make absurd speculations and are poor ambassadors for their position—and for Christianity.[5] But Daniel does not necessarily mean there will be another temple operating in Jerusalem, complete with a restoration of the sacrificial system. It may only mean that worship in general is abolished and, on that interpretation, Gabriel explains this using old covenant language.[6]

Regardless—the antichrist will forcibly stop believers from worshipping the one true God.

How does the prophecy end?

The antichrist will then do two things:

- “On the wing of abominations will come the one who makes desolate.” This probably uses the figure of an over-spreading shadow of darkness and evil (the “wing of abominations”) filling the land. This antichrist makes Jerusalem “desolate” because he has outlawed all worship of the true God—it is now an empty shell. The apostle Paul tells us the antichrist “opposes and exalts himself above every so-called god or object of worship, so that he takes his seat in the temple of God, displaying himself as being God” (2 Thess 2:4).

- Daniel continues: “… until a complete destruction, one that is decreed, gushes forth on the one who makes desolate.” This darkness will spread across the world until the antichrist is suddenly destroyed.

This tells us that antichrist will be completely destroyed, in accordance with a decision God made long ago. In Revelation 19:20, we learn that when Jesus returns: “… the beast was seized, and with him the false prophet who performed the signs in his presence, by which he deceived those who had received the mark of the beast and those who worshiped his image; these two were thrown alive into the lake of fire, which burns with brimstone.”

Now, once Messiah returns (i.e., “the second coming”) and casts antichrist and the false prophet into the lake of fire and locks Satan away in the abyss (Rev 20:1-4), righteousness will reign and all the promises of Daniel 9:24 will come true. The 70 “sevens” end with Christ inaugurating his 1,000-year kingdom reign on earth.

- Immediately after this millennium (“When the thousand years are completed …” Rev 20:7), Satan will be released from prison and lead a rebellion against Jesus’ kingdom, at which point God will vaporize this wicked host with a fireball from on high (Rev 20:7-10).

- Some may protest that, because Satan will quickly find folks to join his rebellion at the end of Christ’s millennial reign, the everlasting righteousness (etc.) Gabriel promised in Daniel 9:24 could not arrived at the beginning of the millennial kingdom.

- But this need not follow—Satan’s rebellion is put down so swiftly and so decisively that sin and wickedness will not reign or have any impact on the world. God smacks this last gasp rebellion down immediately.

So, we are left with antichrist destroyed. Other important passages tell us this happens when Jesus returns, and at that time “THE RIGHTEOUS WILL SHINE FORTH LIKE THE SUN in the kingdom of their Father” (Mt 13:43) and there will be peace on earth. The six-item list from Daniel 9:24 will be accomplished, and the Messianic reign will begin.

[1] Barnes declares “[t]here is nothing in the word here which would indicate who they were …” (“Daniel,” 182, emphasis in original), but he surely forgets that Gabriel told Daniel (9:24) the emphasis of the prophecy was the people of Israel.

[2] See, for example, H.C. Leupold, Exposition of Daniel (Columbus: Wartburg, 1949; reprint; Grand Rapids: Baker, 1969), 431-32).

[3] Joyce Baldwin, Daniel (Downers Grove: IVP, 1978), 191. “Therefore the thought is this: That ungodly prince shall impose on the mass of the people a strong covenant that they should follow him and give themselves to him as their God” (Keil and Delitzsch, Commentary, 9:736).

[4] Walvoord, Daniel, 235.

[5] Michael Svigel, a dispensationalist scholar, writes: “For some reason, the study of eschatology tends to attract a disproportionate number of—let me be blunt—hacks and quacks. End-times hacks produce mediocre, uninformed, trite work for the purpose of self-promotion or money. They ride the end-times circuits tickling ears with sensationalistic narratives, usually resting their interpretations of Scripture on current events or far-fetched conspiracy theories. Or they flood the market with cheap paperback books with red, orange, yellow, and black covers, usually repeating the same worn-out words they used in previous editions of their end-times yarns—sometimes with updates to fit their interpretations with the latest current events. Many of these hacks can be classified as end-times quacks” (The Fathers on the Future: A 2nd-Century Eschatology for the 21st-Century Church (Peabody: Hendrickson, 2024), 24).

[6] Stephen Miller, Daniel, in NAC, vol. 18 (Nashville: B&H, 1994), 272. Leupold suggests that “all organized religion and worship as offered by the church of the Lord are to be overthrown when this prince has his day” (433).