We continue our look at the great prophecy of Daniel 9:24-27. Read the rest of the series.

As we march onward in our study of Daniel 9:24-27, we’ve arrived at Daniel 9:26. What happens after the 69th “seven”? That is, after Daniel 9:25? There is still one “seven” left, and a lot of stuff still to be fulfilled from the six-item list Gabriel revealed in Daniel 9:24. As the prophecy goes on, in Daniel 9:26, two key events happen:

- The Messiah will be “cut off,” and

- “the people of the prince who is to come” will destroy Jerusalem and its temple.

Let’s look at these one at a time.

Messiah and the “gap” between “weeks” 69 and 70

Then after the sixty-two weeks, the Messiah will be cut off and have nothing, and the people of the prince who is to come will destroy the city and the sanctuary. And its end will come with a flood; even to the end there will be war; desolations are determined (Daniel 9:26).

When will the Messiah be “cut off and have nothing”? What does it mean? Considering the bible’s whole story, it seems to suggest Messiah’s death:

He was despised and abandoned by men, A man of great pain and familiar with sickness; And like one from whom people hide their faces, He was despised, and we had no regard for Him … By oppression and judgment He was taken away; And as for His generation, who considered that He was cut off from the land of the living, for the wrongdoing of my people, to whom the blow was due? (Isaiah 53:3, 8).

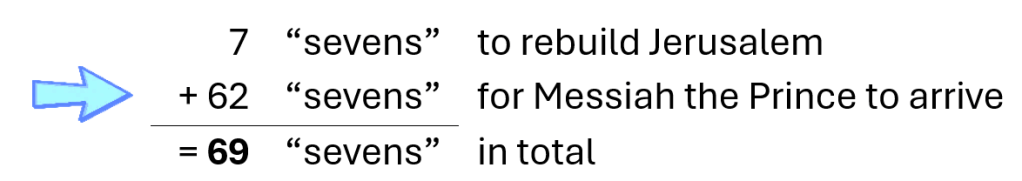

Jesus was despised, rejected, and abandoned—he had nothing. Then he was “cut off”—the Romans executed him. According to Daniel 9:26, this will occur “after the sixty-two weeks …” Remember, there are two sets of “sevens” in Daniel 9:25—(a) seven “sevens,” and then (b) 62 “sevens. The Messiah’s death happens after this second set—the 62 “sevens,” like this:

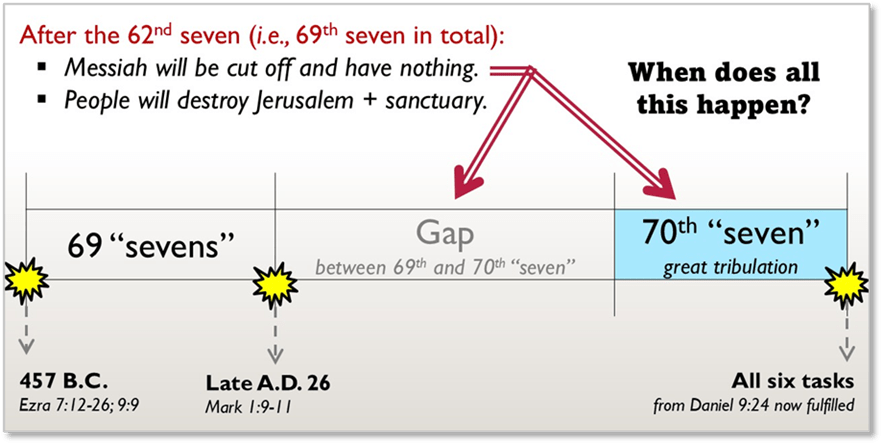

So, while the phrasing is awkward, it seems that the Messiah’s death will happen after the 62 “sevens,” which means after the 69 “sevens.”[1] However, because the 70th “seven” will not begin until Daniel 9:27 (“And he will confirm a covenant with the many for one week …”) it seems there is a “gap” of time here between the 69th and 70th “seven.” If there is no gap, then the 70th “seven” happens immediately—the Messiah dies during the 70th “seven,” because it happened after the 69th “seven.

Evidence suggests there is a gap between “weeks” 69 and 70 because of this chain of logic:

- Because the evidence for the first 69 “sevens” suggests each “seven” is a set of seven years, we are obligated to see the 70th “seven” as also being a set of seven years.

- Because Messiah was “cut off” after the 69th “seven,” we might assume this happened during the 70th “seven.”

- If true, then Jesus was “cut off” at his crucifixion in ≈ A.D. 30.

But …

- This would mean all six tasks in Daniel 9:24 (“Seventy weeks have been decreed for your people and your holy city …”) must take place within seven years of Messiah being “cut off” (A.D. 37-ish)—which must be the case if the 70th “seven” truly followed right on the heels of the 69th.

In other words, if there is no gap between the 69th and 70th seven, then …

- Because each “seven” is seven years,

- and the 70th “seven” begins with Jesus’ death in ≈ A.D. 30 (when he is “cut off”),

- then the 70th “seven” would have ended in ≈ A.D. 37,

- and so all six promises from Daniel 9:24 would have to be fulfilled by A.D. 37.

That did not happen! So, there must be a gap between the 69th and 70th “seven.” Bible-believing interpreters who do not account for this gap are left with an impossible dating problem. So, they are generally forced to take one of two options:

- Option 1: Push the entire thing backwards and make the sinister figure at Daniel 9:27 the wicked Syrian king Antiochus Epiphanes IV, who ruled in the early 2nd century B.C. (read about him in 1 Maccabees 1).[2]

- Option 2: Make the mysterious ruler at Daniel 9:27 be Jesus and wrap the entire prophecy up with Jesus’ ascension to heaven.

Neither of these make the best sense of a straightforward reading of the bible. The “gap” between the 69th and 70th “seven” seems to be the best solution. If true, then the 70th “seven” doesn’t begin until the events of Daniel 9:27, which is yet future. I can’t yet make a full case for the “gap theory” of the 70th “seven” until we wrestle with Daniel 9:27, and that must wait for the next article.

The mystery prince

We now turn to the second event from Daniel 9:26:

Then after the sixty-two weeks, the Messiah will be cut off and have nothing, and the people of the prince who is to come will destroy the city and the sanctuary. And its end will come with a flood; even to the end there will be war; desolations are determined (Daniel 9:26).

The word translated as “prince” means leader, ruler, or a male sovereign other thanthe ruling king (i.e., “the prince”). This means that some ruler will come along one day, whose people will destroy Jerusalem and the temple the Jewish people just re-constructed in Daniel 9:25—the tale told to us in the books of Haggai, Ezra, and Nehemiah.

Well, this makes identification pretty simple—who destroyed Jerusalem (“the city and its sanctuary”) and when did they destroy it?

Daniel says it was “the people of the prince who is to come” (Dan 9:26) who will destroy Jerusalem and its sanctuary. Because the Roman army later destroyed this very city and that very temple in A.D. 70 (some ≈ 600 years after Daniel wrote this prophecy), this means our “prince” in Daniel 9:26 is somehow connected to the Roman empire—which Daniel 7 suggested will exist in three phases.[3]

- Phase 1: The old Roman Empire under whose jurisdiction Jesus and Pontius Pilate lived (Dan 7:23).

- Phase 2: Sometime after Jesus’ day, a splintered remnant that has divided into various pieces (the “10 horns” of the scary fourth beast, Dan 7:23-24).

- Phase 3: A very powerful king who will arise from among the splintered bits of Phase 2 (Dan 7:24-26).

History tells that a Roman general (and later emperor) named Titus Vespasianus destroyed Jerusalem during the First Jewish War,[4] when the Roman empire was still intact in its original form (Phase 1, above). This will be a nasty finish to a brutal war. Gabriel tells Daniel: “… its end will come with a flood; even to the end there will be war; desolations are determined” (Dan 9:26). Now, on the other side of this event, we know that God brought this judgment on his people in A.D. 70 because they rejected the Messiah and Savior whom he sent to rescue them.

The Roman (and Jewish) writer Josephus tells us what happened to Jerusalem when the Romans destroyed it. He knows, because he was there that day.

There was no one left for the soldiers to kill or plunder, not a soul on which to vent their fury; for mercy would never have made them keep their hands off anyone if action was possible. So Caesar now ordered them to raze the whole City and Sanctuary to the ground … [a]ll the rest of the fortifications encircling the City were so completely leveled with the ground that no one visiting the spot would believe it had once been inhabited. This then was the end to which the mad folly of revolutionaries brought Jerusalem, a magnificent city renowned to the ends of the earth.[5]

Josephus tells of one Jewish woman named Mary, driven mad by hunger, who killed her infant son, roasted him, ate one half of him and saved the rest for later[6] (cp. Deut 28:53-57). The temple itself was destroyed by fire in a frenzy of rage by Roman legionnaires who ignored their commander’s orders.

All the prisoners taken from beginning to end of the war totalled 97,000; those who perished in the long siege 1,100,000 … No destruction ever wrought by God or man approached the wholesale carnage of this war.[7]

This must be very hard to hear and understand. We wonder what Daniel thought when he heard this news!

- Daniel asks for assurance from God that he will set everything right (Dan 9:3-19)

- God sends the angel Gabriel to say that he will make it right (Dan 9:20-23).

- In fact, things will be set so right that the six-item list at Daniel 9:24 shows us paradise restored.

- This shakes out with (a) Jerusalem being rebuilt, and then (b) Messiah the prince arriving on the scene (Dan 9:25). This will take 69 “sevens” to happen, but it’ll happen.

Everything sounds great. But then, after the 62nd “seven” (i.e., 69 “sevens” in total):

- The Messiah will be cut off and have nothing (Dan 9:26).

- Jerusalem and its (as yet) un-rebuilt temple will be totally destroyed (Dan 9:26)!

This is a shock. What can it mean? Why will it happen? Why this bizarre reversal? Who is this mysterious prince who is to come? At this rate, Daniel may be thinking, the glorious six-item promise list from Daniel 9:24 seems far, far away. Clearly this is a one step forward, two steps back kind of thing. What is the endgame, here?

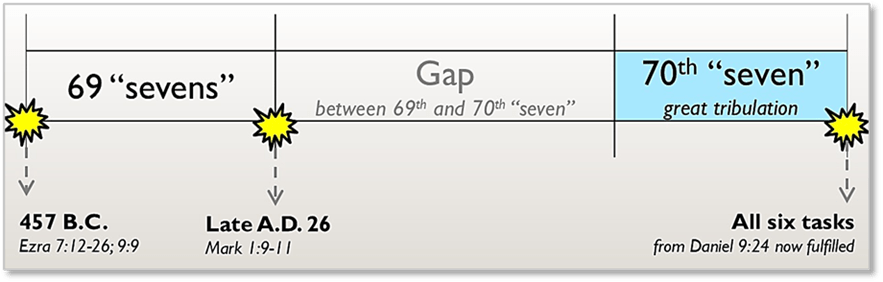

Evidence suggests there will be a long series of events after Messiah’s arrival at his baptism at Daniel 9:25 (the end of the first 69 “sevens”), and before the 70th “seven” begins in Daniel 9:27.

- At least one of those events will be Messiah’s seeming abandonment (“have nothing”), and his execution by Roman soldiers (“be cut off”).

- Another event will be the destruction of the rebuilt temple and the city of Jerusalem by the people of the Roman ruler who will come on the scene (Dan 9:26)—the general Titus, who indeed razed the city in A.D. 70.

- This “intermission” seems to best explain the “gap” between the 69th and 70th unit of seven years in the prophecy.

Nevertheless, in our next article on Daniel 9:27, the angel Gabriel tells us how God plans to make good on his six-item list of promises.

[1] John Gill: “To be reckoned from the end of the seven weeks, or 49 years, which, added to them, make 483 years” (Exposition of the Old Testament, 6:346). Stephen Miller writes: “After the reconstruction of Jerusalem in the first seven sevens (forty-nine years), another ‘sixty-two sevens’ (434 years) would pass” (Stephen R. Miller, Daniel, vol. 18, in New American Commentary (Nashville: B&H, 1994), 267).

[2] This is why Moses Stuart, an outstanding American bible scholar from the early 19th century, remarks: “The third period (one week) of course begins with the same excision of an anointed one, and continues seven years, during which a foreign prince shall come, and lay waste the city and sanctuary of Jerusalem, and cause the offerings to cease for three and a half years, after which utter destruction shall come upon him, vs. 26, 27” (Daniel, 274; emphasis added). Stuart does not consider the possibility of a gap between the 69th and 70th “seven.”

[3] Young, Daniel, 147-50. He is excellent, here.

[4] See this video for free background.

[5] Josephus, The Jewish War, trans. G.A. Williamson, rev. ed. (New York: Penguin, 1969), 7:1 (361). Chrysostom suggests, “And let not any man suppose this to have been spoken hyperbolically; but let him study the writings of Josephus, and learn the truth of the sayings. For neither can any one say, that the man being a believer, in order to establish Christ’s words, hath exaggerated the tragical history,” (“Homily 76,” in NPNF 1.10, 457).

[6] Josephus, The Jewish War, 6:199-219 (341-342).

[7] Josephus, The Jewish War, 6:420f. See ch(s). 13-21 (i.e., 3:422 – 6:429).