Well, I read 54 books this year. They tilt heavily towards biography and the doctrine of scripture. We shall see what 2024 brings. The books are listed in no particular order. Just because I read a book or have something nice to day about it does not mean I agree with everything in it!

1. The Twilight of the American Enlightenment by George Marsden (264 pp.; Basic, 2014).

This was a very good little book. It tells the story of how, at mid-century, the shared ethos of a generic, liberal Protestantism began to fail as an assumed ethos for ethics and public values. Marsden chronicles some efforts to grapple with the problem, and the reactions to these various solutions. In his final chapter, he advocates a “principled pluralism” largely following the outline of Abraham Kuyper’s “sphere sovereignty.” He calls for work to update Kuyper’s framework for the modern era.

2. With Malice Towards None: The Life of Abraham Lincoln by Stephen Oates (544 pp.; Harper, 2011 reprint).

This is the second time I’ve read this biography. It’s very good, long but not too long, and engaging. I highly recommend it. Oates’ volume was dogged with what appear to be baseless charges of plagiarism, which is unfortunate.

3. God, Revelation, and Authority (vol. 1) by Carl F. H. Henry (438 pp.; Crossway, 1999 reprint).

A classic. Henry has an interesting method for theology which relies heavily on logic and order. Even though he makes very good logical sense, his quest to make theology rationally credible does not do justice to the nature of biblical revelation. Bernard Ramm’s little trilogy (Special Revelation and the Word of God, The Witness of the Spirit, and The Pattern of Religious Authority) is a good antidote to Henry’s rationalism. See especially Gary Dorrien (The Remaking of Evangelical Theology) for an outsider’s assessment of Henry’s approach. I suspect that Henry’s God, Revelation, and Authority is more appreciated in a pro forma manner than actually read.

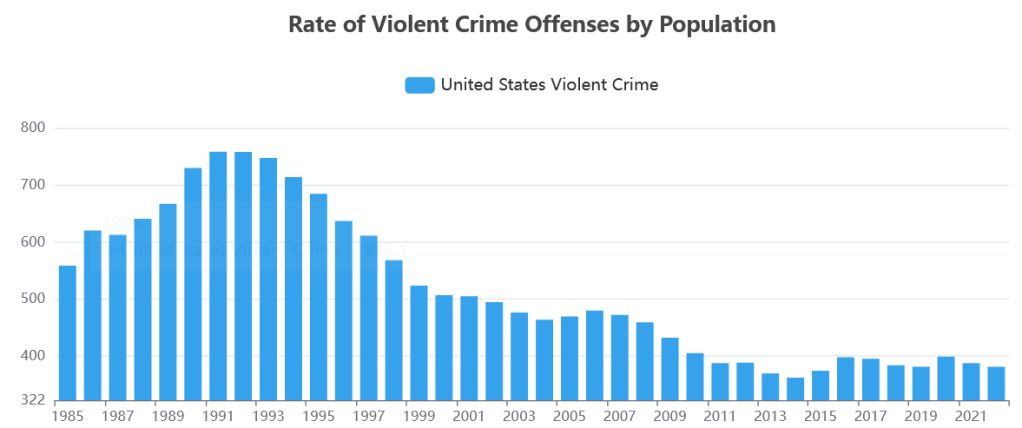

4. Rise of the Warrior Cop: The Militarization of America’s Police Forces by Radley Balko (528 pp.; PublicAffairs, 2021).

A very, very sobering book. Violent crime has in America has been halved since its apogee in 1991 to 1992. Yet, the public perception is that the streets are more dangerous than ever, that law enforcement is under siege. Officers ride around in dark vehicles with tinted windows. They dress like militarized infantry. Why? This book will provide some perspective.

5. The Riders Come Out at Night: Brutality, Corruption, and Cover-up in Oakland by Ali Winston and Darwin BondGraham (480 pp.; Atria, 2023).

In the same genre as Rise of the Warrior Cop, but focusing on police corruption in Oakland. Sobering and astonishing.

6. The Trump Tapes by Bob Woodward (11hrs 29 min; Simon & Schuster, 2022).

You won’t appreciate this unless you listen to the audiobook version, which is just recordings of Woodward’s 20 interviews with then-President Trump. This is perhaps the most damning series of interviews to which I’ve ever listened. From a strategic perspective, it seems the president made a mistake by giving Woodward such unfettered access. However, many of President Trump’s constituents likely do not read Woodward, so perhaps it wasn’t a mistake after all?

7. Peril by Bob Woodward and Robert Costa (512 pp.; Simon & Schuster, 2023).

The third book of Woodward’s Trump trilogy, chronicling the transition to the Biden administration with particular focus on the COVID-19 pandemic response. It’s as horrifying and important as the other two in the series.

8. Rage by Bob Woodward (580 pp.; Simon & Schuster, 2021).

The first of Woodward’s Trump trilogy. It details the Trump transition. It is frightening and paints the picture of Trump as monumentally unfit for any public office–let alone the White House.

9. Biblical Porn: Affect, Labor, and Pastor Mark Driscoll’s Evangelical Empire by Jessica Johnson.

This is a very curious book. It chronicles bits of the Mark Driscoll and Mars Hill Church saga with particular attention to the church’s propagation of a deviant strain of Christian sexuality (i.e. “biblical porn”); particularly how it leveraged its expectations in this area to produce volunteerism, commitment, and loyalty to its peculiar evangelical empire. The ground Johnson covers here overlaps in some areas with the ChristianityToday’s wildly popular “Rise and Fall of Mars Hill” podcast (Johnson published first!).

The peculiar aspect of this book is that it seems to see-saw between an engaging history and sudden esoteric discussions of sociological theory. It reads like two very different pieces melded somewhat awkwardly into one. The discussions of sociological affect seem pasted in with (in some instances) little to no transition. The jarring bit is that Johnson doesn’t really try to translate affect theory for non-specialists. Her academic peers in the same field surely appreciate her remarks along that line, but interested laypeople like me are a bit lost when she veers hard right into academic speak.

In summary, this is a very interesting and informative book that can’t decide whether it wants to be an academic treatise or a popular book for non-specialists. In contrast, it seems to me that Kristin Kobes DuMez faced a similar dilemma with Jesus and John Wayne and chose the popular route, and succeeded quite well. This doesn’t mean Johnson’s book is bad–far from it. I enjoyed it and was horrified at some of what I read. I just wish she’d had interested laypeople like me in mind when she wrote it.

10. A Religious History of the American People (2nd ed.) by Sydney Ahlstrom (1216 pp.; Yale, 2004).

I read about 20% of this book (pp. 385-510, 731-872) while conducting research for a book I wrote on inerrancy and the doctrine of scripture. It is amazing readable, moves fast, and is rightly a classic. I doubt anything like it will come along anytime soon. Mark Noll’s History of Christianity in the United States and Canada is a fraction of this length. Historian Thomas Kidd (Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary) has a book due out in the next year or so which covers some of the same ground, and I am looking forward to it.

11. In Discordance with the Scriptures: American Protestant Battles Over Translating the Bible by Peter Thuesen (256 pp.; Oxford, 2002).

A refreshing and very interesting book about bible translations in America, using the RSV translation’s public reception as a foil. It’s a bit out of date now, especially considering the TNIV gender-inclusive “controversy” from about 15 years ago, and the rise of the ESV.

12. Truth or Consequences: The Promise Perils of Postmodernism by Millard Erickson (335 pp.; IVP, 2001).

This book is what it sounds like–a primer on postmodernism with some of Erickson’s trademark irenic analysis. This is a very helpful book that was part of the “postmodernism is new and weird and we’ll explain it for you” wave of books that conservative Christians put out around the year 2000. Sometimes theologians try to speak outside their lane, and it shows (e.g. Wayne Grudem’s Politics According to the Bible). This doesn’t happen here. Erickson is well-credentialed to respond to postmodernism; he holds an MA in Philosophy from the University of Chicago.

13. America’s Book: The Rise and Decline of a Bible Civilization 1784-1911 by Mark Noll (864 pp.; Oxford, 2022).

This was another book of which I read a portion (pp. 309-582) for research. It’s a very interesting and informative book about just what its title suggests.

14. Religion in the Public Square: Sheen, King, Falwell by James M. Patterson (248 pp.; University of Pennsylvania, 2018).

This was a unique book, because it examined three different paradigms for understanding religion in the public square. Patterson did this by spotlighting three very different individuals; (a) the fiery Roman Catholic radio priest Fulton J. Sheen, (b) the black Baptist preacher Martin Luther King, Jr., and (c) that quintessential representative of white, Southern-style Baptist fundamentalism–Jerry Falwell, Sr.

15. Losing Our Religion: An Altar Call for Evangelical America by Russell Moore (272 pp.; Penguin, 2023).

This is sort of a spiritual sequel to Moore’s 2015 volume Onward! He wrote this book in the aftermath of his resignation from the Southern Baptist Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission and transition to editor-in-chief of Christianity Today. You could say that Moore landed on his feet!

This book is a word of testimony—testimony of what one fellow wayfarer has learned about how to survive when the evangel and the evangelicalism seem to be saying two different things. That requires naming what we have lost—our credibility, our authority, our identity, our integrity, our stability, and, in many cases, our sanity. This book will consider all the ways evangelical America has sought these things in the wrong way—and suggests that perhaps it’s by losing our “life” that we will find it again.

Moore, Losing Our Religion, pp. 21-22

The volume reads a bit like a cathartic exercise from a good man who was deeply hurt by some very unpleasant people who are part of a very unpleasant machine.

I couldn’t help but wonder if the plot twist to the story of American conservative Christianity was that what we thought was the Shire was Mordor all along. I pretend that all of that is past me, but it lingers, in the ringing in my ears of the stress-induced tinnitus that persists to this day, and in the fact that I am still waiting for one sleep without nightmares about the Southern Baptist Convention. But here I am, an accidental exile but an evangelical after all.

Moore, Losing Our Religion, p. 9

This volume fits into a new (post-Trump + 2016) genre that I like to call “white evangelicism sucks and this is why.” It’s not that Moore’s book is bad. It’s not–it’s actually quite good. It’s just that so many people have written (and are still writing) the very same book. They say the same things, in the same way. Of course, perhaps they all say the same things because they all see the same problems. Yes, got it. Understood. I am glad Moore escaped from Southern Baptist public life and I hope he recovers in a spiritually wholesome environment. Still, I’m tired of this genre.

16. Grant by Ron Chernow (1104 pp.; Penguin, 2018).

It’s a biography. It’s very good. Chernow fairly addresses the persistent myth that Grant was a drunken fool. This is probably the best Grant biography in print.

17. Washington: A Life by Ron Chernow (928 pp.; Penguin, 2011).

An excellent biography.

18. Lincoln by David Herbert Donald (720 pp.; Simon & Schuster, 1996).

It’s good. I’m about Lincoln’d out. I’ve read Oates’ volume twice, and now this.

19. Timothy Keller: His Spiritual and Intellectual Formation by Collin Hansen (320 pp.; Zondervan, 2023).

This is an interesting little book. I’m not sure it’s worth the hype its received. That isn’t to say its bad. It’s an interesting sketch of the influences that made Tim Keller the unique and gifted man that he was.

20. The Pattern of Religious Authority by Bernard Ramm (117 pp.; Eerdmans, 1959).

The first volume in Ramm’s trilogy of authority in the Christian life. Ramm places great emphasis on the Spirit being the channel by which God speaks to His people. A very good and very helpful book.

21. The Witness of the Spirit by Bernard Ramm (142 pp.; Wipf and Stock, reprint, 1960).

The second volume in Ramm’s trilogy. He and Carl Henry have very different approaches. He eschews Henry’s cold rationalism and emphasizes the Spirit’s dynamic and dialogical role in the Christian life. Ramm was heavily influenced by Calvin’s own treatment on the Spirit, and it shows. I really appreciate Ramm. He is the kind of theologian I want to be when I grow up!

22. Special Revelation and the Word of God by Bernard Ramm (221 pp.; Eerdmans, 1961).

The final volume in Ramm’s trilogy. In an era before the Chicago Statement (1978) set the guardrails for the debate for a new generation, Ramm took a mediating position that was still in the conservative orbit. In the modern era, the Chicago Statement is a non-negotiable article of faith for conservative institutions and many churches. Ramm would not have fit easily into that mold.

23. The Scripture Principle by Clark Pinnock (284 pp.; Harper Collins, 1984).

Pinnock’s plea for a conservative alternative to the Chicago Statement. Well-reasoned and irenic, but firm. Modern evangelicals who assume “orthodoxy = the Chicago way or the highway” ought to read Pinnock. They might be pleasantly surprised. I cannot speak to the two revised editions of the book which Pinnock put out with a co-author. I recommend only the original, 1984 edition.

24. The Authority and Interpretation of Scripture: An Historical Approach by Jack Rogers and Donald McKim (564 pp.; Wipf and Stock, 1999 reprint).

Whenever you mention this book to conservative theologians, they will likely respond within 10 seconds with “but, did you read Woodbridge’s reply?” That tells you that Rogers/McKim stuck a nerve. This is an extraordinary work that surveys the historical data about how Christians have understood the nature of scripture. The issue of Chicago-style inerrancy lurks in the background as Rogers/McKim’s rhetorical foe–they conclude that the Chicago Statement is not the historical position of the church. I cannot agree with everything in the book, and Woodbridge gleefully documented reams of purported errors–I leave the reader to evaluate whether his criticisms are valid. Still, a must-read.

25. Preaching: Communicating Faith in an Age of Skepticism by Timothy Keller (320 pp.; Penguin, 2016).

26. The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine, Volume 5: Christian Doctrine and Modern Culture (since 1700) by Jaroslav Pelikan (414 pp.; University of Chicago, 1991).

A very good survey of Christian doctrine.

27. A History of Christian Thought Volume 3: From the Protestant Reformation to the 20th Century, revised ed. by Justo Gonzalez (498 pp.; Abingdom, 2009 reprint).

An excellent survey–I prefer it to Pelikan.

28. The Use of the Scriptures in Theology by William Newton Clarke (192 pp.; Charles Scribners, 1905).

Clarke is the poster-child for gentle, kind, 19th century Baptist liberalism. His doctrine of scripture disgraces God, but he is so kind and grandfatherly that you almost like the guy.

29. The Rise and Fall of Dispensationalism: How the Evangelical Battle over the End Times Shaped a Nation by Daniel Hummell (400 pp.; Eerdmans, 2023).

An important volume on an important topic. Dispensationalism has fallen on hard times. It has little to no scholarly influence, has no reliable academic press, has very few scholars publishing anything to advance the system, has produced precious few technical commentaries, and few substantive mid-level (e.g. NAC, Tyndale, or EBC level) commentaries. In that sense, it has indeed “fallen” from great heights. This book provides one explanation about why and how.

30. The Remaking of Evangelical Theology by Gary Dorrien (262 pp.; Westminster John Knox, 1998).

A tour-de-force survey of evangelical theology from a liberal outsider. This is one of the best books I read in 2023. His survey of theological perspectives is fair and irenic, and his footnotes will take you to valuable works from conservatives.

31. Scripture, Authority, and Interpretation by Dewey Beegle (332 pp.; Eerdmans, 1973).

Beegle’s book is another entry from the 1970s to 1980s genre which I’ll call “the Chicago Statement is wrong!” Some of his critiques of Chicago-style inerrancy are interesting, but on the whole Beegle goes off the reservation here. If you want a conservative alternative to the Chicago Statement, see Pinnock and not Beegle. F.F. Bruce wrote an endorsement!

32. The Princeton Theology 1812-1921: Scripture, Science, and Theological Method from Archibald Alexander to Benjamin Breckinridge Warfield edited by Mark Noll (344 pp.; Baker, 1983).

This is an edited volume containing lengthy excerpts from four “old Princeton” theologians on scripture, science, and theological method. Noll provides brief introductions but largely lets the authors speak for themselves. An invaluable book. Warfield and A.A. Hodge are excellent on scripture–much better than R.C. Sproul, who drafted the original 1978 Chicago Statement and somehow misunderstood the “original autograph” issue along the way–compare the Chicago Statement to Warfield’s “The Inerrancy of the Original Autographs” (1883) and you’ll see what I mean.

33. Between Faith and Criticism: Evangelicals, Scholarship, and the Bible in America (2nd ed.) by Mark Noll (284 pp.; Regent College, 2004).

This is mostly inside baseball stuff for academia, but it has some interesting insights. It explores how to reconcile faith and critical inquiry. It’s a logical sequel to the Princeton volume or Noll’s The Bible in America book.

34. The Fifth Risk by Michael Lewis (256 pp.; Norton, 2019).

A forgettable little book about how President Trump’s administration was allegedly so inept and how everything may crumble to bits at any moment. Not worth buying. Glad I checked it out from the library. It repeats the same theme in every chapter; (a) Lewis introduces the noble civil servant, then (b) in come the stupid Trump officials in 2017, then (c) the dumb Trumpian appointees threaten to ruin everything, then (d) Lewis lets the noble bureaucrat explain how dangerous the Trump appointees are, then (e) the next chapter repeats in a different government sector. Very tiresome and a bit condescending.

35. Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion by David Hume–ed. Richard Popkin, 2nd ed. (160 pp.; Hackett, 1998).

Hume annoys me.

36. “Essay VI—On Judgment,” in Essays on the Intellectual Powers of Man, by Thomas Reid, edited and abridged by A.D. Woozley (517 pp.; MacMillan, 1941).

Reid’s emphasis on common sense, on what every rational person can know by his innate faculties, is very good. Philosophers today seem to be scornful of commonsense realism, so this makes me wary. But, Reid just makes sense. I suppose one main hurdle is that Reid makes sense in a world in which one is willing to acknowledge that God has created us and given us logical faculties for reason. We don’t live in that world any longer, so I suspect that disconnect is driving some of the disagreement.

37. The Bible in America: Essays in Cultural History edited by Nathan O. Hatch and Mark A. Noll (192 pp.; Oxford, 1982).

An extraordinary series of essays from world-class historians. Not sure why it’s out of print!

38. Wilson by A. Scott Berg (880 pp.; Penguin, 2014).

A magisterial biography of a very interesting man. It made me very sad to read of Wilson’s incapacitation shortly after his second term began. I wonder what he could have accomplished if he’d retained his physical powers.

39. Hoover: An Extraordinary Life in Extraordinary Times by Kenneth Whyte (768 pp.; Knopf Doubleday, 2018).

The best book I read in 2023. Hoover was a true genius. His story is inspiring beyond words. He came from nothing, made a career as a brilliant mining engineer, then a financier of sorts in the mining world, then saved untold millions from starvation as head of a humanitarian agency (what would now be an NGO) during and after the first world war. Secretary of Commerce. Elected President. If there was any single individual in American history who could have been up to the task of combating the series of crises that we now refer to as the Great Depression, it would have been Hoover. And yet, he couldn’t get it done.

Whyte works hard to bring perspective to Hoover’s reactions to the financial crises. He argues that Hoover responded as well as could be expected, that Franklin Roosevelt cribbed several of his policies and ideas (even the infamous “nothing to fear but fear itself” line), and that the depression was on the road to recovery when Roosevelt assumed office–but that the latter refused to coordinate policy with Hoover and went his own way. Whyte notes that the depression continued until the second world war, that Roosevelt did not “solve” the depression, and that Hoover was understandably bitter about the treatment he received. Roosevelt was undeniably a superior politician, and Hoover was dealt a bad hand … not unlike Jimmy Carter nearly 50 years later.

I plan to read another Hoover biography in 2024. This man deserved better. He truly was an extraordinary man in extraordinary times.

40. Watergate: A New History by Garrett M. Graff (832 pp.; Simon & Schuster, 2023).

Anything you want to know about Watergate? You’ll find it here. This is the most up-to-date, exhaustive account of the scandal in print. An outstanding book.

41. The Struggle of Prayer by Donald Bloesch (196 pp.; Helmers & Howard, 1988).

Excellent little book.

42. Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America by Rick Perlstein (896 pp.; Scribners, 2009).

Nobody would confuse Perlstein with an objective historian. This is an entertaining, exhaustively researched work of cultural history with a sarcastic tone. That isn’t to say it isn’t valuable. His quartet of books chronicling the rise of the political right from Goldwater to Reagan is essential reading, and extraordinarily entertaining.

43. American Individualism by Herbert Hoover (91 pp.; Doubleday, 1922).

Hoover published this little book while he was Secretary of Commerce. He outlines what he sees as a peculiarly American kind of individualism–a characteristic which sets America apart:

Therefore, it is not the individualism of other countries for which I would speak, but the individualism of America. Our individualism differs from all others because it embraces these great ideals: that while we build our society upon the attainment of the individual, we shall safeguard to every individual an equality of opportunity to take that position in the community to which his intelligence, character, ability, and ambition entitle him; that we keep the social solution free from frozen strata of classes; that we shall stimulate effort of each individual to achievement; that through an enlarging sense of responsibility and understanding we shall assist him to this attainment; while he in turn must stand up to the emery wheel of competition.

Hoover, American Individualism, pp. 9-10. Emphasis added.

Hoover believed we must make our own way; that we must be guaranteed equality of opportunity but not equality of outcome. The grand object of government is to (a) foster equality of opportunity without (b) throttling individual initiative:

To curb the forces in business which would destroy equality of opportunity and yet to maintain the initiative and creative faculties of our people are the twin objects we must attain. To preserve the former we must regulate that type of activity that would dominate. To preserve the latter, the Government must keep out of production and distribution of commodities and services. This is the deadline between our system and socialism. Regulation to prevent domination and unfair practices, yet preserving rightful initiative, are in keeping with our social foundations. Nationalization of industry or business is their negation.

Hoover, American Individualism, pp. 54-55

One can see glimmerings of the modern GOP here. This is a very interesting book. Well worth reading and pondering. Needless to say, Hoover despised Roosevelt’s New Deal.

44. Eisenhower in War and Peace by Jean E. Smith (976 pp.; Random House, 2013).

A good biography. It seems to lose steam once it hits Eisenhower’s presidency. And, yes–Eisenhower surely had an affair with Kay Summersby. Smith suggests that Eisenhower planned to divorce Mamie and marry Kay, but his plan was thwarted. Like a good general facing hard realities, Eisenhower then sent Kay a “Dear John” letter that is astonishingly cruel and heartless. He cut her loose like a used Kleenex. Eisenhower comes across as an amazing politician and a great leader, but a poor general. That is fair, I believe.

45. Truman by David McCullough (1120 pp.; Simon & Schuster, 1992).

This book made me love Truman. It has earned its reputation. I even bought a “The Buck Stops Here!” desk sign replica from the National Archives. I will display it on my desk at work.

46. Reagan: An American Journey by Bob Spitz (880 pp.; Penguin, 2019).

A great biography of an interesting guy. Reagan was a good man, a kind man, a decent man. He also seemed to be shallow and a bit of an empty suit.

47. Our Faith by Emil Brunner, trans. John Rilling (153 pp.; Scribners n.d.).

I love these little “this is what the Christian faith is about” books that theologians sometimes write. This is a great book.

48. The Soul of Prayer by P.T. Forsyth (109 pp.; Regent College (reprint), 2002).

A classic on prayer. Probably the most quotable book I’ve ever read.

49. Faith and Justification by G.C. Berkouwer, trans. Lewis Smedes (201 pp.; Eerdmans, 1954).

A great book on justification. It’s refreshing to read something plain and scriptural on this essential topic from the era before the new perspective on Paul clouded everything.

50. His Very Best: Jimmy Carter–A Life by Jonathan Alter (800 pp.; Simon & Schuster, 2021).

I don’t believe the “great” Carter biography has yet been written. This book more describes than explains. I don’t know why Carter is such an inflexible moralist. I don’t know why he’s a theological liberal. I don’t know why he wanted to go into politics. I don’t know much about his relationship with his kids. I don’t know how this inflexible man managed to build a coterie of professionals around him who took him to the Georgia governor’s mansion and eventually to the Presidency. I don’t know why he was such a bad and seemingly clueless politician (he famously didn’t try to remain friends with the Democratic Party). I know all these things happened, but I don’t know why. Still, Alter’s biography is informative. It’s probably the best one available to date.

51. Atonement and the Death of Christ: An Exegetical, Historical, and Philosophical Exploration by William L. Craig (328 pp.; Baylor, 2020).

An outstanding book by a world-class philosopher and theologian.

52. Whither? A Theological Question for the Times by Charles A. Briggs (334 pp.; Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1889).

Briggs wrote this book in great frustration. He had been hounded for years by conservatives within his Presbyterian denomination over his doctrine of scripture and inerrancy. He believed the Princeton school was erecting bulwarks that were impossible to hold. He disagreed vehemently with that perspective’s reading of the historical record and believed inerrancy was a recent invention by pious men who were reacting against realities they did not want to acknowledge. It deserves to be read, regardless of whether one agrees with Briggs.

53. The Bible Doctrine of Inspiration: Explained and Vindicated by Basil Manly, Jr. (278 pp.; A.C. Armstrong and Son, 1878).

A sensible and wise volume on the doctrine of inspiration from a Southern Baptist theologian. Worth reading.

54. Revelation and Inspiration by James Orr (224 pp.; Duckworth & Co., 1910).

Another wise and sensible book on the doctrine of scripture from a Scottish evangelical. Conservatives who follow the Chicago-style of inerrancy generally do not like Orr’s volume. I think it has some very good material.