Jesus ascended back to heaven 40 days after his resurrection. We know this because Luke tells us (Acts 1:3). It’s a very important event, and Luke is the guy who wrote both accounts of it. One is shorter (Lk 24:50-53), and the other is a bit longer (Acts 1:10). Other New Testament writers constantly reference it, too.

Why talk about the ascension?

One big reason is that the Christian story makes no sense without it.

- The bible tells us that Jesus is coming back—but coming back from where?

- The bible says that Jesus is the shepherd for all believers. If that’s true, then where is his “shepherd command center”? Is he in Olympia? In Atlanta? In London? In Durban?

- If Jesus pours out the Holy Spirit, where does he pour it out from? Is he in a house somewhere in West Olympia, pouring out the Spirit onto new believers in Tokyo? Even the imagery of “pouring out” suggests a spatial position above us somewhere—but where?

- If Jesus left this earth to prepare a place for us, at what location is he making these preparations?

A helpful analogy to start

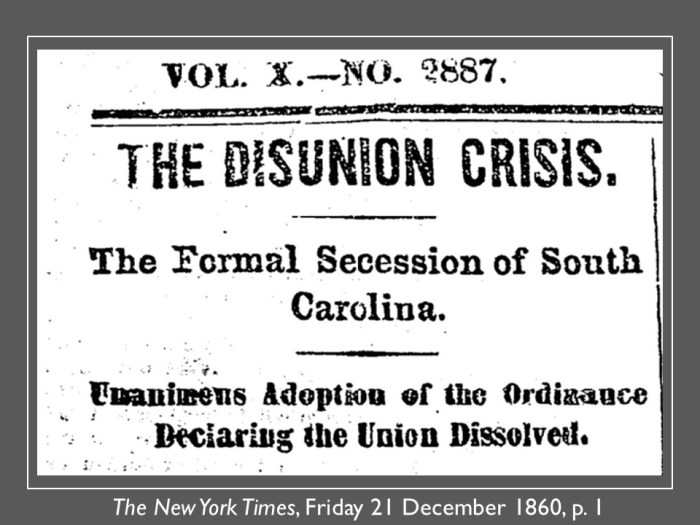

Here’s an analogy that helps explain the difference between Jesus’ ministry during the incarnation and now—after the ascension. The analogy is the difference between tactical and strategic command, in a military context.

- A tactical commander is focused on a specific, local objective with a relatively small number of resources. He and his men must take that hill, right there. This is a very narrow focus.

- A strategic commander sees the whole picture—not just that hill, but all the hills. The whole battlespace. The logistics. The reinforcements. The larger plan for the entire campaign.

Jesus’ incarnation v. ascension is like that:

- The incarnation was a tactical command situation. Jesus and a relatively small band of followers wandered to and fro in a very small area, among a fairly small group of people, as he trained a very small cadre of followers. Jesus didn’t worry about what is now China, India, or Argentina. He focused on Capernaum, the Sea of Galilee region, and other local areas.

- But, at his ascension Jesus pinned back on his Fleet Admiral (5-star) insignia and began running the entire cosmic war from his combat information center at the Father’s right hand. He now acts “from Washington” (as it were) to impact individual “commands” at far-flung outposts (large and small) all across the world.

- This is tactical v. strategic command.

Goals for studying Jesus’ ascension?

Jesus performs at least three big jobs in heaven:

- He’s the King who wages divine war against Satan.

- He’s the High Priest who reconciles us to God and always lives to make intercession for his people (see Heb 5-10). I covered this during my ascension sermon in 2024, and you can watch it here.

- He is our shepherd and guide—this will be our focus in this article.

This article has two goals:

- To show us why the ascension is such an important part of the Christian story.

- To know why Jesus’ ascension is a good thing for you, and why it should comfort you.

We’ll make our way through this in three steps:

- We’ll look at some (not all) hints from the old covenant, and their fulfillment in the new covenant scriptures so we can “see” the ascension throughout the bible.

- Next, we’ll consider where, exactly, heaven is. Have you ever thought about that?

- Finally, I’ll provide five reasons why the ascension matters today for you if you’re a Christian.

I could say much more on this topic (especially on Jesus as king and high priest), but we’ll stick to the “Jesus as shepherd” theme here.

From Hints to Reality

I’ll discuss two old covenant hints about the ascension, and two new covenant texts that show these hints have now become reality.

Two old covenant hints

The first old covenant hint we’ll consider that points to Jesus’ ascension is the Day of Atonement ritual. You can find this by comparing Leviticus 16 and Hebrews 9.

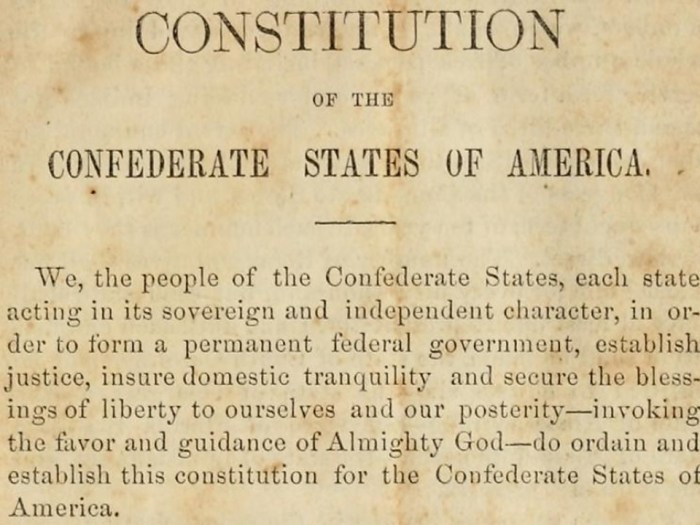

- You have the tabernacle and its sturdier replacement, the temple building. The bible explains the elaborate rituals the covenant member and the priest perform to atone for the sins of the people. These are foreshadowing’s (or “types”) that signal a greater fulfillment by Jesus in the new covenant (Heb 9:1-9)—the same way a little boy’s tricycle foreshadows his first car.

- The tabernacle and its furnishings inside the holy of holies also “stand for” the heavenly realities above (Ex 25:9)—they’re like LEGO figurines of the true reality (Heb 8:5).

- So, in old covenant worship, on the Day of Atonement that high priest goes in, offers the blood of the sacrificed animal, and makes atonement for the people.

So far, so good.

But how does Jesus make this picture become real? How does he complete the reality to which the old covenant LEGO mini-figures pointed? He completes it by going to the real throne room in heaven, offering his own blood from his own sacrifice, and making permanent atonement for his own people. This means Jesus must leave here and go back to heaven to complete the picture—this is the ascension.

Next, we turn to King David, who certainly understood at least something about this. Consider Psalm 110:1, which is the most quoted text in the new covenant scriptures! “The LORD says to my lord: ‘Sit at my right hand until I make your enemies a footstool for your feet.’”

Jesus used this text to explain that the Messiah was more than just David’s son—he was a divine figure. He asked folks who the Messiah would be, and they said it would be David’s son (Mt 22:42). Well, Jesus asked, how could David (who spoke by means of the Holy Spirit) call his own son his lord (Mt 22:43)? “If then David calls him ‘Lord,’ how can he be his son?” (Mt 22:45).

Look back at Psalm 110:1 (above), and think with me here:

- There are two “Lords” in this verse. One is Yahweh, whose personal name our English bibles always translate in ALL CAPS, so we’ll catch it. We’ll call him “Lord 1.”

- But who is this other “lord,” the one not in capital letters? We’ll call him “Lord 2.”

- Whoever Lord 2 is, he seems to be divine—this was Jesus’ point in Matthew 22:42-46. What person could sit beside God in heaven? So, Lord 2 is divine, and the Christian story tells us it is Jesus.

- Fair enough—but if Lord 2 is Jesus, and Jesus came here during the incarnation, then how does he get back there to take his seat and pin back on his 5-star, Fleet Admiral insignia?

Well, he leaves.

He ascends back to where he’d been before the world began. He went back to heaven. He’s gonna stay there “until I [Lord 1] make your enemies a footstool for your feet” (Ps 110:1). The apostle Peter understood this, which is why he quoted Psalm 110:1 and said: “Therefore let all Israel be assured of this: God has made this Jesus, whom you crucified, both Lord and Messiah” (Acts 2:36).

Remember the tactical v. strategic analogy we mentioned earlier. Now, since the ascension back to the throne room in heaven, Jesus the king is directing this multi-front, cosmic and divine war from heaven until all his enemies (Satan and his minions) are crushed in the dust before him.

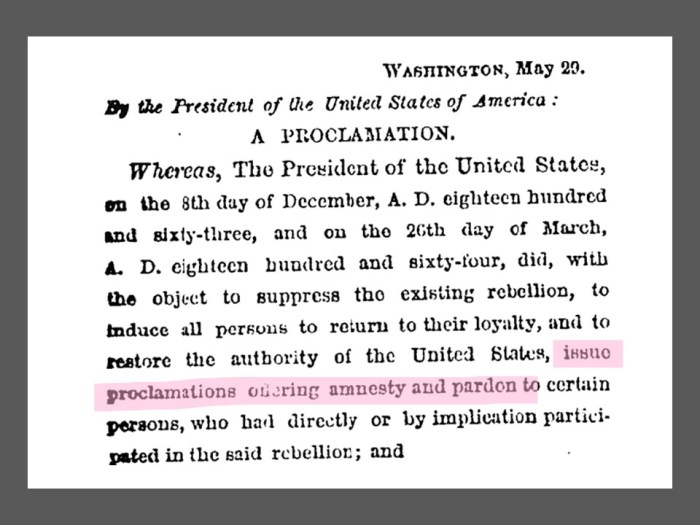

Two new covenant realities

The apostle Peter preaches that “[h]eaven must receive him”—that is, Jesus the Messiah—“until the time comes for God to restore everything, as he promised long ago through his holy prophets” (Acts 3:21). When heaven receives Jesus, we have the ascension, which will terminate when Jesus once more descends here with the heavenly host to crush Satan and his minions under his feet (Rev 19; Mt 24:29-31).

The martyr Stephen, whose sad story God preserved for us in Acts 7, saw the risen Christ in heaven after his ascension. When Stephen denounces the Jewish council— “[y]ou stiff-necked people! Your hearts and ears are still uncircumcised. You are just like your ancestors: You always resist the Holy Spirit!”—he faces almost certain death. At that crucial moment, Luke tells us:

… Stephen, full of the Holy Spirit, looked up to heaven and saw the glory of God, and Jesus standing at the right hand of God. “Look,” he said, “I see heaven open and the Son of Man standing at the right hand of God” (Acts 7:55-56).

Jesus is not here. He is “up there,” in heaven. He ascended. And, of course, the Christian story tells us that Jesus is coming back here one day. From where is he coming back? From heaven.

Where is heaven?

I won’t spend too much time here, but it is something many Christians probably haven’t thought about much. I’ll only skim through this one, but it’s worth thinking about. Where is heaven? Here’s what we know:

- Jesus is clearly not here.

- He is also clearly somewhere else, in some real, physical, actual place. We know this because Jesus keeps his physical, resurrected body, which must take up real estate somewhere.

- Jesus taught us to pray “Our Father, who art in heaven” (Mt 6:9), which means the Father is also taking up real estate somewhere. Yes, God is spirit and has no innate physical form with which to occupy a space, but he is “up there” in heaven.

- And we know that Jesus will one day come back to here from that place.

But where is it?

- It isn’t up in the sky. God isn’t in outer space! If you leave earth’s atmosphere, you won’t find him there. Or on the far side of the moon. Or hiding in one of Saturn’s rings.

- But heaven seems to be a physical place somewhere.

So, it’s best seen as a different dimension—a divine alternate realm that’s above this one.

Heaven is the place where God is. It isn’t a fixed address—it moves when God moves. This is why the apostle John tells us that, one day, God will re-locate from heaven to earth. He will bring heaven to earth, just as he promised through the prophet Zechariah (Zech 2:10).

I saw the Holy City, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride beautifully dressed for her husband. And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, “Look! God’s dwelling place is now among the people, and he will dwell with them. They will be his people, and God himself will be with them and be their God (Revelation 21:2-3).

But, for now, “heaven” is this alternative divine dimension where Jesus went at his ascension.

Five ways Jesus shepherds Christians from heaven

Because Jesus is our good shepherd, he’s our guide who cares for us in this life and brings us along to the next. Israel’s leaders (“shepherds”) were basically terrible. Worthless. Unreliable. Bad. It’s not that Jewish people were habitually bad. It’s that all of us are habitually bad! We need a leader from outside to get us out of this mess.

God told us that he’d send a special someone to do a proper job.

10This is what the Sovereign LORD says: I am against the shepherds and will hold them accountable for my flock. I will remove them from tending the flock so that the shepherds can no longer feed themselves. I will rescue my flock from their mouths, and it will no longer be food for them. 11“‘For this is what the Sovereign LORD says: I myself will search for my sheep and look after them. 12As a shepherd looks after his scattered flock when he is with them, so will I look after my sheep. I will rescue them from all the places where they were scattered on a day of clouds and darkness (Ezekiel 34:10-12).

That special someone is Jesus, God’s one and only Son. “I am the good shepherd. The good shepherd lays down his life for the sheep” (Jn 10:11).

- But remember, he’s not here—so where is he?

- He’s your shepherd from heaven.

- Remember the analogy of tactical v. strategic command. During his three-year ministry, Jesus exercised local, tactical command in a small place—he shepherded a small, local flock.

But now, since his ascension, Jesus runs the whole show across the entire world. He shepherds the entire flock from the “combat information center” up there, in heaven.

What difference does this make for our lives? Here are five things Jesus does for you from heaven.

First—Christ is shepherding you to spiritual maturity

When Christ ascended on high, he led captivity captive, then gave gifts to his people (Eph 4:8). This means Jesus captured “captivity” itself—by defeating Satan, sin and death—and took it away with him to heaven to imprison it forever.[1] This is imagery, like that of the woman representing sin who Zechariah says was crushed into the basket and carried off to exile far to the east in Babylon (Zech 5:5-11).

Why does Christ do this? Why does he remove captivity from his people and give them gifts (Eph 4:11)? To equip his people for service, so we’d each “grow up” into a mature community in Christ (Eph 4:12).

Jesus is orchestrating all this for you, from heaven. God’s children aren’t generic, faceless numbers—Jesus even says we’re his brothers and sisters (Heb 2:11). Your spiritual maturity matters to Jesus, and that happens in relationship with a local community of Jesus people somewhere that the NT calls “a church.”

Second—Jesus is preparing paradise for you

Jesus said: “My Father’s house has many rooms; if that were not so, would I have told you that I am going there to prepare a place for you? And if I go and prepare a place for you, I will come back and take you to be with me that you also may be where I am” (Jn 14:2-3).

In the garden of Eden, which I’ll call Paradise 1.0, we had physical bodies, we were with God in a perfect creation, in perfect relationship with him, and we used our talents and gifts to build a perfect world.

But that ended pretty quickly and pretty badly.

At the end of the Christian story, in Paradise 2.0 (see Rev 22), we will have that same paradise reality—only this time it will be permanent. Jesus paves the way for Paradise 2.0 by his ascension—everyone who believes in him will follow him to heaven (Jn 14:6). Then, one day he’ll bring all his people to the new creation here to defeat Satan and kick off Paradise 2.0 (Rev 19:11-21).

Jesus can’t do any of that if he stays here. This is why he went there to prepare paradise for you. “[B]y his own appearance there for them with his blood, righteousness, and sacrifice, he is, as it were, fitting up these mansions for their reception, whilst they are by his spirit and grace fitting and preparing for the enjoyment of them.”[2]

Third—Jesus empowers you for evangelism

Jesus said: “Very truly I tell you, whoever believes in me will do the works I have been doing, and they will do even greater things than these, because I am going to the Father” (Jn 14:12). In what way will Christians “do even greater things” than the works Jesus has been doing?

Jesus led people out of darkness and into the light. Jesus rescued people from Satan. He brings people into God’s forever family. Jesus said he fulfills all of God’s covenant promises. Jesus said he could fix you, fix your life, and give you meaning and purpose as an adopted child of God.

What does that have to do with you? With the ascension?

Well, Jesus gives you the power to do the same thing as he did—even quantitatively greater things—because we preach and tell the same message that has the same results. And Jesus orchestrates all this from on high, through the Holy Spirit “because I am going to the Father.” From the Father’s side in heaven above, Jesus is working in your life, and through you in the life of local churches, to spread his message around the world.

A very wonderful promise! But has it been fulfilled? We think it has. For if we look at the wonders of the Day of Pentecost, together with the events that followed in the rapid spread of the gospel during the apostolic age, it does not seem extravagant to regard them as greater than any which took place during the ministry of Christ. And if we compare the spiritual results of the three most fruitful years of the ministry of Paul, of Luther, of Whitefield, or of Spurgeon, with the spiritual results of Christ’s preaching and miracles for three years, we shall not deem his promise vain.[3]

Fourth—Jesus sends the Holy Spirit to rescue people

The bible records Jesus words: “When the Advocate comes, whom I will send to you from the Father—the Spirit of truth who goes out from the Father—he will testify about me. And you also must testify, for you have been with me from the beginning” (Jn 15:26-27).

It is Jesus who poured out the Holy Spirit at Pentecost (Acts 2:32-33). It is Jesus who opens people’s hearts so they believe and trust the gospel (Acts 16:14; 2 Cor 4:3-6). Our passage in John 15:26-27 tells us that:

- Jesus goes back,

- and then he sends the Spirit,

- who then helps us and testifies to us about Jesus,

- and we then bear witness to Jesus and his gospel,

- and the Spirit testifies about Jesus in the hearts of those whom we reach.

There is no wiggle room here—the Spirit “will testify about me.” He will. He shall. It’s a promise. We bear witness, and the Spirit will testify about Jesus.

Fifth—Jesus is with us, everywhere at once

During his ministry, Jesus was constantly with his people. His physical body limited him to being in a particular place, at a particular time. There are only 24 hours in a day—even for the incarnate Jesus.

So, how can Jesus be with his people, if his people are in Judea, Samaria, and the uttermost parts of the earth? How can Jesus be in all these places at once? Will he hop on a Zoom call with us once per week from wherever he’s at? Wouldn’t, then, our relationship with Jesus be like a long-distance relationship? We know how those go …

The answer is that, since the ascension, Jesus will be with each of us spiritually.

I will not leave you as orphans; I will come to you. Before long, the world will not see me anymore, but you will see me. Because I live, you also will live (Jn 14:18-19).

Christians will not be orphans, which means Jesus won’t abandon us when he ascends back to heaven— “I will come to you.” We will actually see him, and we will “live” because he lives (i.e., after his resurrection).

What does all this mean? “On that day you will realize that I am in my Father, and you are in me, and I am in you” (Jn 14:20).

- On the day Jesus comes to us to not leave us as orphans,

- we will realize that Jesus is in union/relationship with his Father,

- and that we are in union/relationship with him,

- and that he is in union/relationship with each of us.

This is Jesus’ spiritual presence with every individual believer, knitting us to him, to one another, and to the Father, by the power of the Spirit. This is an invisible but tangible bond that, as it were, fuses our souls to his at a level that’s marrow deep.

This is a reality that evidently could not happen if Jesus had continued to skulk around Galilee forever after his resurrection, content to remain a tactical commander in this cosmic war. Instead, he ascended back to heaven to assume strategic command of the whole battlespace, re-pinned on his Fleet Admiral insignia, and now guides each of us personally and individually.

And so, because Jesus is with all his people right now from heaven above, he can promise us: “Peace I leave with you; my peace I give you” (Jn 14:27). He tells us all this—these five reasons and others— “so that you will not fall away” (Jn 16:1).

Jesus’ ascension matters. It’s good that he went away. It’s good that he’s running (and winning) this divine war. It’s good that he sends the Spirit to rescue people. And it’s good that we await his return, so the Father can bring heaven to earth forever.

[1] Scholars old and modern are divided over how to understand this “captivity captive” language, and the various English translation choices reflect this (see, for example, the NIV—which disagrees with my interpretation here). For my interpretation see John Gill, An Exposition of the New Testament, vol. 3, The Baptist Commentary Series (London: Mathews and Leigh, 1809), 87–88).

[2] Gill, Exposition, 2:56.

[3] Alvah Hovey, Commentary on the Gospel of John, in American Commentary (Philadelphia: American Baptist Publication Society, 1885), 286.