This essay (see the series) aims to help ordinary Christians rightly consider the relationship between the church and the state. This is important because Christians receive many contradictory messages about this issue. Some Christian influencers call for believers to “take America back for God.” Others just want good, old-fashioned Christian values to influence society, and they feel marginalized because Mayberry is gone and isn’t coming back. Still others just want the church to have nothing to do with politics—perhaps to the extent that their churches neglect to speak truth to a decadent culture.

So, there’s good reason to consider the “church v. state” issue with some fresh eyes—to go back to basics. I won’t address everything about this large topic, but I hope to establish a foundation for thinking about this issue the right way. This essay consists of six articles, of which this is the first.

In this introductory article I’ll sketch two paradigm shifts which impact any discussion along this line from an American context, introduce three common operating environments in which churches often operate, and provide a preview of this essay’s conclusions. Then, I’ll spend the bulk of the essay discussing five foundational principles that will help us work through the “church v. state” issue. I labored to ground these principles firmly in the biblical storyline, rather than in creeds, confessions, or political theology. This doesn’t mean I don’t value tradition; it just means first principles on important issues ought to be explicitly or implicitly scriptural.

Paradigm shift no. 1—the death of “Christendom” and the like

In the 20 centuries (and counting) since Jesus’ first advent, Christians in the West have often operated in an environment that assumed a church and state nexus. Since the time of Constantine, the church had presumed it would have the support of the state and of the culture around it. The tremors of the Enlightenment cracked this wide open.

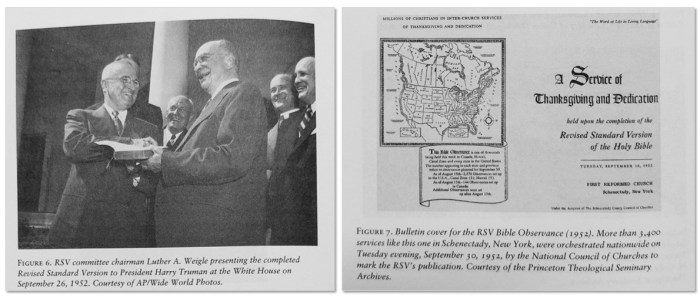

But, even after this earthquake, the church still occupied a position of unquestioned influence and status in many nations—a defacto Christian-ish ethos pervaded. For example, as late as 1952 the National Council of Churches launched a $500,000 advertising blitz to promote the Revised Standard Version translation of the bible and publicly presented President Harry Truman with his own copy[1]—this is unthinkable in 2023.

This situation began to change rapidly in the mid-20th century, when for perhaps the first time in its history the church in the Western world began to grapple with how to understand its role vis-à-vis the state as a minority community in a self-consciously secular world.[2] Some flavors of the American church have long responded to this with a defensive impulse which stems from its memory of a different time, when “while the state was not officially Christian, society seemed to promote values that were deemed essentially Christian.”[3] Whether this idyllic reality existed at meaningful scale outside of 1950s television sets is open to question.[4] However, that era is gone, secularism is here, the church has a minority status, and one theologian aptly likened this new world to an airplane flying blind without instruments, not knowing where it is or where it’s going.[5]

Certain American believers sometimes react by trying to re-Christianize society on a superficial level—to recapture a largely imaginary lost glory. One Christian historian described Victorian-era America as having “a veneer of evangelical Sunday-school piety” that amounted to “a dime-store millennium.”[6] It’s still common to hear older believers complain about the demise of compulsory prayer and bible reading in public schools. This ghost of a so-called “Christian nation” is a monkey some flavors of the American church have trouble shaking off its back—it often lurks in the background in the guise of a Christian-ish American exceptionalism or super-patriotism.

Paradigm shift no. 2—Christianity shifts to the global south

The second paradigm shift for the church v. state issue is that many, many Christians now live in an environment that never knew Christianity as a civil religion[7] and are not handicapped by that cultural memory. Over the past 120 years, Christianity has at last become a truly global phenomenon. For many centuries, since the Arab conquest of the Mediterranean basin in the early 7th century, Christianity had been largely a Western religion.[8] But, as one church historian has noted, the period between 1815 to 1914 (the great age of missions) “constituted the greatest century which Christianity had thus far known.”[9] This missions movement produced a church that is now global and no longer beholden to the patronage of Western benefactors. These so-called “younger churches” are hungry, energetic, and often far outpace the enthusiasm and vitality of their Western “parents.”

There were now new centers in every continent, resulting in a map of Christianity that, rather than seeing it as having its base in the West, and from there expanding outward, sees Christianity as a polycentric reality, where many areas that had earlier been peripheral have become new centers … the new map of Christianity does not have one center, but many. Financial resources are still concentrated in the North Atlantic, as are educational and other institutions. But, theological creativity is no longer limited to that area.[10]

Indeed, most Christians now live nowhere near Europe or North America.

In 1900, 82% of Christians lived in the North. By 2020 this figure had dropped dramatically to just 33% … The future of World Christianity is largely in the hands of Christians in the global South, where most Christians practice very different kinds of the faith compared to those in the North. Christianity has shifted from a tradition that was once majority global North to one that is majority global South.[11]

Many of these Christians did not grow up in a “Christianized” culture, and so their thinking of the church and the state isn’t colored by sepia-toned memories of a bygone age. We can learn from these brothers and sisters and better appreciate the limitations of our own situation. So, for example, when an Argentine theologian critiques the culture Christianity of the “American Way of Life,” the American church ought to listen to its brother:

Christian salvation is, among other things, liberation from the world as a closed system, from the world that has room only for a God bound by sociology, from the “consistent” world that rules out God’s free, unpredictable action … The gospel, then, is a call not only to faith but also to repentance, to a break with the world. And it is only in the extent to which we are free from this world that we are able to serve our fellow men.[12]

This is a call to, among other things, divorce oneself from secular values and allegiances—including political ones. Perhaps because the author doesn’t come from a context where Christianity has been a civil religion, he can read the New Testament without explicitly or unwittingly conflating church and state—and that makes him (and others) worth listening to.

Three common operating environments for the church

Broadly speaking, churches operate in one of these three operating environments:

- Church in alliance with the state. In this arrangement the church and the state are generally bound together. Legislation and public policy will allegedly be informed by purportedly Christian values. This can take various forms. Theonomy envisions the church as the state (basically a theocracy);[13] the populist rhetoric from what is sometimes misleadingly labeled as “Christian nationalism” is downstream from some aspects of this theory. Constantinianism refers to the state controlling the church—when the Roman Emperor Constantine converted to faith he made Christianity the state religion and presided over councils about Christian doctrine as both the head of state and as the alleged head of the church. In Western Europe, many nations still retain the emaciated shell of a state church—even though that influence is now largely symbolic. Or, in a softer version of the same, varieties of American exceptionalism[14] advocate for America’s special role in God’s providence and its resulting obligation to honor God in all it does, or at least America’s role as “a communal paragon of justice, freedom, and equality.”

- Pluralism. This is also known as a “free church in a free state.” The idea is that government’s role is to preserve law and order and provide freedom for citizens to pursue their own religious path or none at all. The state is more of a neutral arbiter or policeman who keeps order.[15] The first amendment to the U.S. Constitution embodies this ethos in its “free exercise” and “establishment” clauses—the government cannot establish a religion or prohibit its free exercise.[16] The 1948 United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights also reflects this perspective.[17] Baptist churches which understand their heritage (and not all do) have always been champions of this ethos.

- Isolation. In its milder forms, this means Christians create their own alternative subcultures for reality (think about the movie The Village). Or, it can mean a church deliberately never speaks of “political issues” and chooses to not teach believers how to engage these topics as responsible citizens. Or, in perhaps its most extreme form, it can take the form of monasticism.[18]

Many Americans Christians of a certain age and subculture are probably most comfortable with some version of American exceptionalism. On the other hand, some Christians are sick of it all and don’t want any hint of “politics” in the church. Other Christians believe church and state ought to stay separate, each minding their own business—their interests may overlap but their roles and functions are different.[19] Still others are theonomists who want a Christian America. Even more aren’t quite sure what they want and are falling prey to populist, bastardized variations of theonomy-ish talk from right-wing politicians who may or may not actually believe what they say.

What do the scriptures say? Do they provide a way out of this confusing maze?

Five principles—a preview of coming attractions

Here are a preview of the five foundational principles that I believe provide a solid, biblical basis for considering the “church v. state” question. These come from an unapologetically Baptist milieu, and some readers will spot this fairly quickly. Here they are, with a brief description.

- There are two kingdoms, Babylon and Jerusalem. Babylon will lose. This is the most fundamental truth about human history, the biblical story, and reality.

- God’s kingdom is distinct from every nation state. If we conflate America (or any nation) with the kingdom, we’re making a terrible mistake. “The church is the community of God’s people rather than an institution, and must not be identified with any particular culture, social or political system, or human ideology.”[20]

- A Christian’s core identity is as a child of God and a kingdom citizen, and so her principal allegiance must be to God’s kingdom (“Jerusalem”) and not to a nation state. If you’re a Christian, then God doesn’t much care that you’re an American. You now have a kingdom passport, kingdom citizenship, and a kingdom mandate. To the extent our most basic identity is rooted in America rather than God’s kingdom, then we are traitors.

- The church’s job is to be a kingdom embassy; a subversive and countercultural society calling outsiders to defect from Babylon and pledge allegiance to Jerusalem. “We argue that the political task of Christians is to be the church rather than to transform the world … The church exists today as resident aliens, an adventurous colony in a society of unbelief.”[21]

- Set apart, yet not isolated. The analogy of “church v. state” compared to “home v. work” is helpful. Christians must approach political and social issues as self-conscious outsiders with a kingdom agenda—to tell God’s truth to Babylon. A pluralist operating environment is the best operating environment for a local church.

I hope this brief sketch of the church v. state issue is helpful for you and provides a sure foundation for considering a question that will only get trickier in the coming years. Future articles in this series will discuss each of these five principles in detail.

[1] Peter Thuesen, In Discordance with the Scriptures (New York: OUP, 1999), pp. 4, 90.

[2] This is an important caveat, because the long Baptist struggle for religious liberty took place within a Christian-ish milieu. What I’m referring to is the church as a minority community in an overtly secular world.

[3] Justo Gonzalez, Christian Thought Revisited: Three Types of Theology, rev ed. (New York: Orbis, 1999), p. 128.

[4] See especially David Halberstam, The Fifties (New York: Fawcett Columbine, 1993), ch. 34.

[5] See Carl F.H. Henry, Toward a Recovery of Christian Belief (Wheaton: Crossway, 1990), ch. 1.

[6] George Marsden, Understanding Fundamentalism and Evangelicalism (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1991) p. 10.

[7] A civil religion is “a religion, or a secular tradition likened to a religion, which serves (officially or unofficially) as a basis for national identity and civic life,” (s.v. “civil,” see s.v. under “compounds,” OED Online. March 2023. Oxford University Press. https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/33575?redirectedFrom=civil+religion (accessed May 08, 2023)). I’m distinguishing this from “Christendom” in which an alleged Christianity has an external and superficial role as a traditional religion (s.v. “christendom,” noun, no. 3c, OED Online. March 2023. Oxford University Press. https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/32437?redirectedFrom=christendom (accessed May 09, 2023). For example, many Latin American countries have a “Christendom” background because of their Roman Catholic heritage, but it’s not necessarily a basis for national identity or civic life—read the Latin American liberation theologians.

[8] Justo Gonzalez, The Story of Christianity, vol. 1, rev. ed. (San Francisco: HarperOne, 2010), pp. 288-294. See also Kenneth S. Latourette, A History of Christianity, vol. 1, rev. ed. (New York: Harper & Row, 1975), pp. 286-291.

[9] Kenneth S. Latourette, A History of Christianity, vol. 2, revised ed. (New York: Harper & Row, 1975), p. 1063.

[10] Justo Gonzalez, The Story of Christianity, vol. 2, revised ed. (San Francisco: Harper One, 2010), pp. 525, 526.

[11] Gina Zurlo, Global Christianity: A Guide to the World’s Largest Religion from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Academic, 2022), pp. 3-4.

[12] Rene Padilla, Mission Between the Times: Essays on the Kingdom, revised ed. (Carlisle: Langham, 2010), p. 42; emphasis in original. This essay is the presentation Padilla gave at the 1974 Lausanne Conference.

[13] On “theocracy,” I mean “[d]omination of the civil power by the ecclesiastical,” (John MacQuarrie, s.v. “theocracy,” in The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Ethics, ed(s). James Childress and John MacQuarrie (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1986), p. 622).

On theonomy, see Rousas Rushdoony, Christianity and the State (Vallecito: Chalcedon, 1986). “A Christian theology of the state must challenge the state’s claims of sovereignty or lordship. Only Jesus Christ is lord or sovereign, and the state makes a Molech of itself when it claims sovereignty (Lev. 20:1-5). The church of the twentieth century must be roused out of its polytheism and surrender. The crown rights of Christ the King must be proclaimed,” (p. 10). Emphasis added. Theonomists often insist they do not endorse sacralism and want God-ordained institutions to remain in their own spheres of authority. Yet, one of the church’s jobs is to insist that “every sphere of life [including the government] must be under the rule of God’s word and under the authority of Christ the King,” (Christianity and the State, p. 9). Thus, they would argue this is not a church and state alliance at all. I believe this is a distinction without a meaningful difference.

[14] I’m drawing from John Wilsey’s discussions of “closed” and “open” American exceptionalism, respectively (American Exceptionalism and Civil Religion: Reassessing the History of an Idea (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2015), pp. 18-19).

[15] See especially Raymond Plant, s.v. “pluralism,” in Westminster Dictionary of Christian Ethics, pp. 480-481.

[16] For a trustworthy, plain language discussion of the historical context and legal interpretation of the religion clauses, see Congressional Research Service, “First Amendment Fundamental Freedoms,” in Constitution Annotated, https://constitution.congress.gov/browse/amendment-1/ (accessed 08 May 2023).

[17] Article 18: “Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.” https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights.

[18] On monasticism, see Kenneth S. Latourette, A History of Christianity, vol. 1 (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1975), pp. 221-235.

[19] “Church and State might in a perfect society coalesce into one; but meantime their functions must be kept separate,” (Edgar Y. Mullins, The Axioms of Religion (Philadelphia: American Baptist Publication Society, 1908), p. 195).

[20] Lausanne Covenant, Article 6.

[21] Stanley Hauerwas and William Willimon, Resident Aliens: Life in the Christian Colony, expanded ed. (Nashville: Abingdon, 2014), pp. 39, 48.