Pope Francis’ recent death is an opportunity for bible-believing Christians to consider what we ought to believe about the papacy. The goal is not to dance on a dead man’s grave, but to think about who oversees Christ’s church. Is the papacy a legitimate institution? Does it have biblical warrant?

The Catechism of the Catholic Church (“CCC”) says that:

- Peter is the rock of the church, which is built upon him (CCC, Art(s). 881, 552).

- Peter has the “keys” and therefore governs the church (CCC, Art(s). 553, 881).

- Peter is the shepherd of the church, and priests and bishops have derivative authority under Peter.

- Peter is the source and foundation of the unity of the church—he has full, supreme, and universal power (CCC, Art. 882).

- According to the first Vatican council (Vatican I, 1869-70, Session 4), if you do not agree with Rome’s teaching about Peter, you are damned to hell.

This is all false and cannot be defended from scripture. Rome’s argument, both in the CCC and at Vatican I, centers on Matthew 16:18 and some supporting citations. My argument here focuses on the Matthew 16 passage. If you want to read more about Rome’s grave and terrible errors about the gospel, I recommend (a) James White, The Roman Catholic Controversy (Minneapolis: Bethany House, 1996), and (b) Tyler Robbins, “How Rome Distorts the Gospel—Atonement Misunderstood.”

Now—on to the papacy!

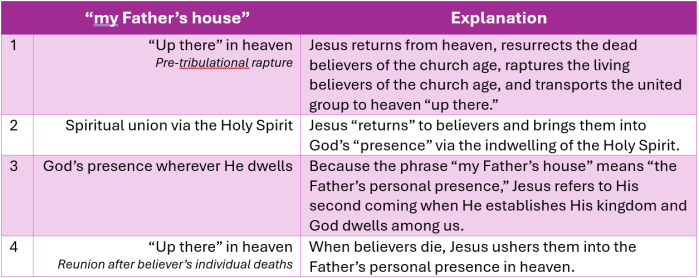

In Matthew 16:18-19, Jesus gives us two pairs of images: (a) the rock and the gates, and (b) the keys and the bonds. What do they mean? Oracles from “the Greek” won’t help you here—your bible translation is just fine. Whatever these images mean, they must make the best sense of what the passage is taking about in context.

Context—what are we talking about here?

Jesus asks his disciples who people say the Son of Man is (Mt 16:13). He refers to himself as the mysterious figure from Daniel’s famous vision (Dan 7:13-14). Public opinion says that Jesus is a prophet of some sort (Mt 16:14). Now, Jesus asks the disciples who they think he is (Mt 16:15). Peter answers: “You are the Messiah, the Son of the living God” (Mt 16:17).

The “Messiah” is the chosen and anointed one, the special divine envoy (“Son of the living God”) who will make all God’s covenant promises come true. He is God’s promise-keeper. He makes God known to us (Jn 1:18). Jesus agrees and tells Peter that his Father in heaven has revealed this precious truth (i.e., his confession about Jesus’ identity) to him.

So, as we move on to consider the first pair of images, we must get this right—this conversation is about Jesus’ identity and what it means. Any interpretation that takes a hard turn off this road to something completely different is wrong.

Imagery 1—The Rock and the Gates

Jesus says: “And I tell you that you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of Hades will not overcome it” (Mt 16:18). Here we have our first pair of images.

- What are gates for? To keep people in or out.

- What is Christ’s church build on? A rock.

- Because Hades’ gates cannot prevail against the rock, these gates are imprisoning folks inside, and the rock smashes this gate open to set them free.

So, whatever “the rock” is …

- The entire family of God is built on it,

- and the rock is so strong, and so powerful,

- that Satan’s kingdom can’t withstand it!

- so it’s a pretty tough rock— divinely tough!

You have three options:

- The rock is Peter—the pope.

Rome places great stock in a Greek wordplay that Jesus uses here: “And I tell you that you are Peter (Πέτρος—petros), and on this rock (πέτρᾳ—petra) I will build my church …” This is a weak argument. Unless context suggests otherwise (and remember, the context is Jesus’ identity and what it means), there is no need to see this as anything other than a playful wordplay.

For example, my first name is Mark. Yet my parents have called me Tyler all my life, so I have no idea why they bothered to name me Mark. A similar wordplay would be if someone told me: “Your name is Mark, and mark my words that …” That is all this need be. Peter has nothing to do with this conversation—they’re talking about Jesus’ identity.

- The Rock is Jesus.

When he says, “and upon this rock,” he points to himself. This is weak and desperate. The pronoun translated “this” refers to something nearby in the context. This position rightly rejects Peter as the rock (because it is out of context), and to make Jesus himself “this rock,” they must make him point to himself. There is a simpler way—one that doesn’t require us to pantomime while explaining it.

- The rock is Peter’s confession of Jesus’ identity and what it means—his faith and trust in the Messiah.

Option 3 is the right option.[1] Christ’s church family is built on the confession that Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of the living God. You cannot be a Christian (and a member of the worldwide Jesus family) unless you trust and confess the truth about him. Again, remember the context of this passage—this whole conversation is about who Jesus is and why it matters. It is not about a disciple who Jesus is going to call “satan” in four verses. It is not about the disciple who Paul rebuked to his face in Antioch (Gal 2:11-14). It is not about the guy to whom nobody in the scripture gives special authority.

But the conversation certainly is about Jesus, the Messiah, the Son of God. This explains why the rock is so strong, and so powerful, and why the gates of Hades can’t prevail against the church—because it’s divinely tough.

The completed imagery of rock + gates is this:

- The rock is the confession that Jesus is the divine promise-keeper and Son of God.

- The gates are to Satan’s kingdom, and they can no longer imprison those who believe in the rock.

- Jesus (the rock) smashes these gates open—remember the divine rock which smashes the statue of pagan empires (which are really different flavors of Babylon, Satan’s kingdom) at Daniel 2:34-35, 44.

Peter cannot smash these gates open. Yet, this is what the “rock + gates” imagery would have us believe. Your safety, security, and anchor is Jesus. It wasn’t John Paul II. It wasn’t Benedict. It wasn’t Francis. It is not Leo. It’s the Messiah, the Son of the living God—just like the old song says— “On Christ the solid rock I stand. All other ground is sinking sand.”

Imagery 2—The Keys and the Bonds

Jesus continued: “I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven; whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven” (Mt 16:19).

- What are keys for? To control access. To let you in or out.

- What do bonds do? They confine you. Imprison you.

We know that Jesus has the keys of life and death (Rev 1:18), the keys that lock people into that future, or let them out to embrace a better one tomorrow.

So, whatever the keys are,

- They let you into the kingdom of heaven,

- and untie or unchain you from the bonds that you’re in,

- which means this is a divine power.

You have two options to understand what this means:

- Peter has exclusive power to govern the church (the keys), and to absolve people’s sins by a sacred power—the bonds (CCC, Art(s). 553, 881, 1592).

This makes no sense of the “key” imagery. Keys are about access (Rev 1:18, 9:1, 20:1), not governance. Scripture never says to go to Peter—or anyone else—to have your sins absolved. Nor does Peter later claim this right for himself in his two New Testament letters. Instead, the bible tells us that God forgives sins—even David knew this (Ps 51:1-2).

- Peter (and every other Christian) offers “the key” to freedom by preaching rescue (“the bonds”) through complete forgiveness of sins.

Option 2 is the correct one. Again, this entire conversation is about who Jesus is and why it matters. The keys don’t belong to Peter when Jesus speaks—he says he will give them to Peter (future-tense). Later, Jesus clarifies that the entire church has the keys—he even repeats the very same words (Mt 18:18).

The “key + bonds” imagery tells us this:

- Jesus’ family,

- organized into big and small Jesus communities around the world called “churches,”

- are his hands and feet that offer the key to spiritual freedom,

- by preaching liberation, forgiveness, and reconciliation.

- and we untie the shackles or bonds by accepting people into the brotherhood of the faithful upon a credible profession of faith (see Acts 2:41).

Jesus, through his communities around the world, unlocks the gate to death and hades and lets his people out, just like the song says— “my chains are gone, I’ve been set free, My God, my Savior has ransomed me!”

Peter was a good guy. Peter was an important guy. Peter is a star (not the star) of Acts 1-11. But Peter was just a guy.

Jesus leads his church. Not by one old man in Rome, but by Word + Spirit in his churches around the world, under qualified leaders, through you, and me, and us. And together we build Jesus’ family—just like Peter himself told us. Jesus is the “living stone” (a synonym for “rock”) to whom we come to be built up into the spiritual household of the faithful (1 Pet 2:4-5).

Your leader is not an old man in a white robe who sits in a building financed over 500 years ago by extorting money from millions of peasants with stories of fraudulent “indulgences” that can buy them time off a purgatory that doesn’t exist, and who represents a false “gospel” that has no perfect peace—that doesn’t make you holy and perfect forever (Heb 10:10, 14). Instead, thank God (literally) that the confession and trust in Jesus is your rock. Jesus is your anchor. Jesus smashes open Hades’ gates. Jesus has the keys and loans them to his churches. Jesus, through his communities across the world, unlocks the door to death and Hades to let his people out of darkness and into the marvelous light.

[1] Many conservative Protestant scholars today believe that Peter is the rock. They often comment that Protestants only object to this interpretation because of what Rome does with the passage. See John Broadus’ wonderful commentary on the Gospel of Matthew for a representative example of this line of thinking: https://tinyurl.com/4my9e7y3.

I believe this is wrong, and I have not found the arguments convincing. The context strongly supports Option 3, and it is the best antecedent for the pronoun in ἐπὶ ταύτῃ τῇ πέτρᾳ οἰκοδομήσω μου τὴν ἐκκλησίαν. This is not an academic article, so I will leave the matter here!