Introduction[1]

Fade in on the little town of Bomont, presumably in rural Illinois. At a pulpit in a small local church is the Reverend Shaw Moore. He’s fond of crazed pastoral rants against dancing. You may recognize him—he’s the angry pastor-dad from Footloose.

There are still some Reverend Shaw’s around—less than there used to be, but still plenty everywhere. He epitomizes the wrong way to think about the sexual and gender confusion in our society.

What should Christians think about Pride Month?

This article is not about “why it’s wrong.” It’s not a list of “unstoppable” answers to “destroy” the opposition. Instead, it’s a proposal for a better way to think about these issues. It proceeds in five stages:

- A snapshot of reality in 2022—a quick assessment for the church

- Stories or scripts … and you

- The LGBTQ script

- The Christian script

- What should Christians think about Pride Month?

Where We Are—A Frank Assessment of Reality in 2022

I’ll share three snapshots of the reality of life in the West, in 2022. These are not crazed stories from dark corners on the web. They’re from mainstream news outlets:

Trans people are … cathedrals?

The first anecdote is a short video from Middle Church, in New York City. This church has a pastor on staff who boasts in his bio that he won the seminary drag contest. The video’s thesis is that “trans people are cathedrals.”[2] Like cathedrals, trans people are always in flux, always being remodeled, expanded, contracted—being restored. And like cathedrals, the narrator intones, trans bodies are sacred, holy spaces.

Sarah and Dickie

In Dusseldorf, there lives a 23-year-old woman named Sarah Rodo, who wishes to marry her toy Boeing 737, which she’s named “Dicki” (for reasons about which I dare not speculate).[3] One news article features Sarah clad in lingerie, bathed in a deep red light, cradling Dickie in her arms. The caption notes, “Sarah says she is particularly attracted to Dicki’s face, wings and engine.”[4]

Sweet Miku

Thirdly, I present a Japanese man who has married a plush doll depicting a fictional anime character:[5]

… life with Miku, he argues, has advantages over being with a human partner: She’s always there for him, she’ll never betray him, and he’ll never have to see her get ill or die. Mr. Kondo sees himself as part of a growing movement of people who identify as ‘fictosexuals.’

What does this reality mean?

It means people increasingly have no idea what Christianity is or what it means—it’s parallel to us recoiling at Sarah and poor Dickie! And, because nothing is more personal than sex or felt identity, this means there will only be increasing confusion and anger at Christians as we oppose the sexual redefinitions entrenched in our society. So, we need to explain the Christian story to them like they know and understand nothing—because they probably don’t. We need more than, “Jesus loves you, and has a wonderful plan for your life.” That means nothing to many people, today.

If that is the case, then I suggest three wrong approaches that will likely have to die, especially regarding sexual ethics, because of this reality:

First: a retail (“come to me”) evangelism model is weak, and it always has been.

The “if we have the event at the church building, they will come!” mindset needs to die. If you are in the rural or semi-urban Midwest or South, this may not apply.

Second, the death of the confrontational model.

Because of the cultural disconnect between Christ and culture, “one off” evangelistic encounters are likely not enough by themselves to be successful[6]—the “gap” is too much! Could one conversation with Sarah (the plane girl) convince you to initiate a sexual relationship with a toy plane? That’s the “gap” you’re dealing with, in some cases. This gap will only grow!

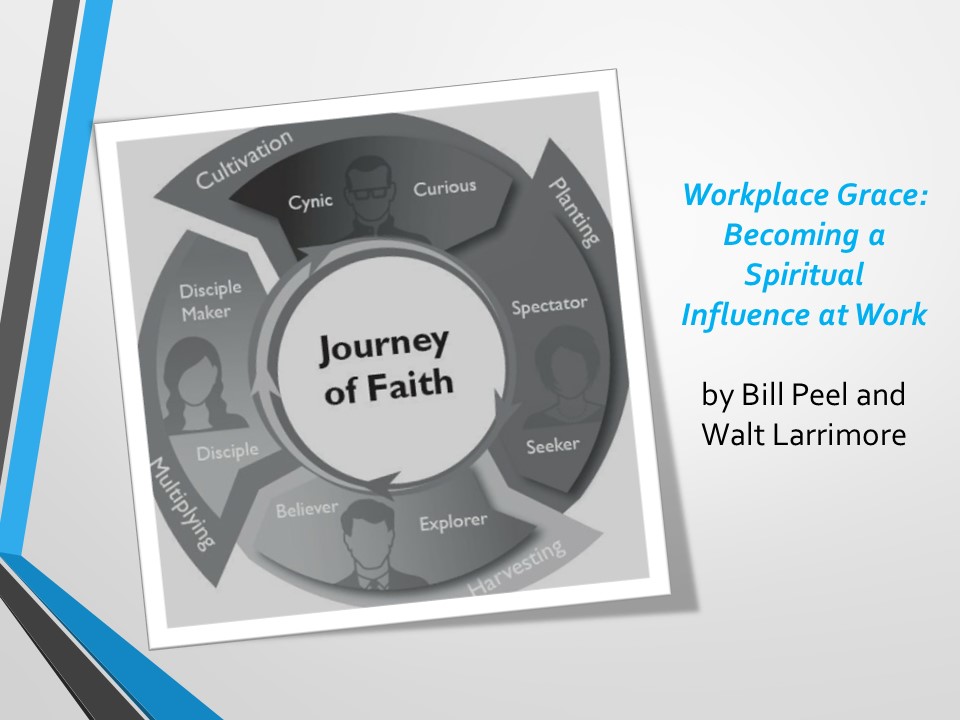

Salvation is a cultivating process[7] (e.g. parable of the sower, Mt 13:3-8—see also the Rainer model[8]), so relationships and roles are important. When you have a relationship with people, you earn the right to speak truth. In this cultivation cycle, you don’t always know your role—you’re likely a waystation on the person’s spiritual trajectory.

Third, lots of law, but little or no grace.

This is Rev Shaw’s way. The vibe is not evangelism, but disgust and distance. You change your statement of faith to “keep the gays away.” You amend your by-laws so “they” can’t “force you” to use your church building in a way you disapprove. The goal is isolation from “those people.” This is the default model in many traditional churches—usually led by older pastors from a different era

So, we need something more—we need to “tell the better story.” Accordingly, there are at least two wrong attitudes that achieve nothing that we ought to throw overboard:

First, don’t be full of anger and outrage.

This common attitude is directly opposite to what the parable of the weeds and the wheat tell us (Mt 13:24ff).[9] In that parable, the field is the world. Jesus likens the kingdom situation to this world. What’s the situation? The world is a mess—a mixed bag. Good wheat is intermingled with the weeds. The kingdom’s servants ask whether they ought to go pull the weeds up. Jesus says no—wait until the end, and the angels will harvest the field appropriately. Until then, this world will remain a mess.

This false model assumes:

- The world should be a pure world—a Christian world,

- But, it ain’t like that,

- So, that makes us mad,

- So, we wage a crusade to “take America back” for God.

This is a lie. The true model, from the parable, is that this world is and will remain very messy. So, sexual and gender confusion reign. Big surprise! The second wrong attitude is just as deadly:

Second, don’t be warm Jello.

In our quest to “listen,” we forget God really does have something to say about sexual ethics—and has a message of liberation from wrong ideas and desires.

What’s Your Story?

Everyone has a “story” or a “script” that shapes their view of the world. The filter thru which they interpret things, understand themselves, and their place and role in the world. It answers the “big questions” of life. This “script” also answers more immediate, practical questions:

- Who do I love?

- Who can I love?

- What is a man?

- What is a woman?

- How do I know who am I?

- What’s expected of me and how do I live up to it?

So, the Japanese guy who married a doll has a story.

Sarah Rodo, the plane girl, has a story.

People confused by their gender have a story.

People confused about their sexual feelings have a story.

You may not like it or understand it, but they each have a script that they’ve made up or adopted that makes their choices “make sense” to them and gives them an identity.

Mark Yarhouse, a Christian psychologist out of Wheaton College who specializes in sexual and gender issues, identifies three stages for identity:[10]

- Dilemma. My experiences and feelings are not what’s “normal” or “expected.”

- Development. The business of finding, sorting, and weighing answers to these dilemmas.

- Synthesis. Your solution to the problem—you figure out “who you are” and come to some conclusions.

How you sort all this out depends on what “script” or “story” you find most persuasive about life. Like actors with their scripts for their roles, our “script” gives us our cues, tells us our lines, and lets us know what’s expected of us—“this is your part, this is your role, and this is how we expect you to play it.”

For example, in some generic flavors of American culture today:

- A 19-year-old boy can’t come back to live at home, because that would make him a loser. But, a girl of the same age can come home without stigma.

- A man who sleeps around is a hero, but a woman who does the same is morally bankrupt.

- A man “should” like hunting, fishing, shooting guns, and grilling. A woman “should” like Hobby Lobby, journaling, and Lifetime movies.

None of these are biblically mandated, but they’re real, they’re out there, and they’re “the script” many of us accept as “the way things are.” We learned the script at home, at school, from friends, from family, from experience. They’re baked into everything. The key tell is that these scripts are more felt or implied, than explained.

We have “lines” for sexual feelings + gender, too—but what if these roles don’t fit you very well? Someone’s gonna hand them a new script, a different script—one that claims to “explain” their feelings. It’ll either be the world’s script—the LGBTQ script—or it’ll be Christ’s script. Or it’ll be both. But someone’s gonna hand them a script.

The LGBTQ Script[11]

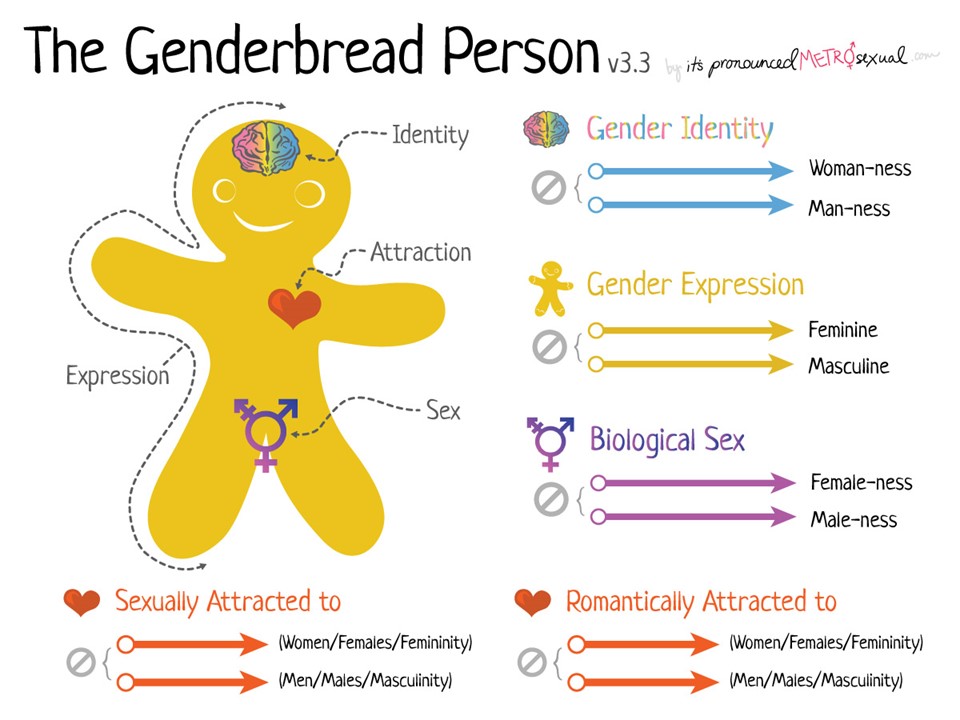

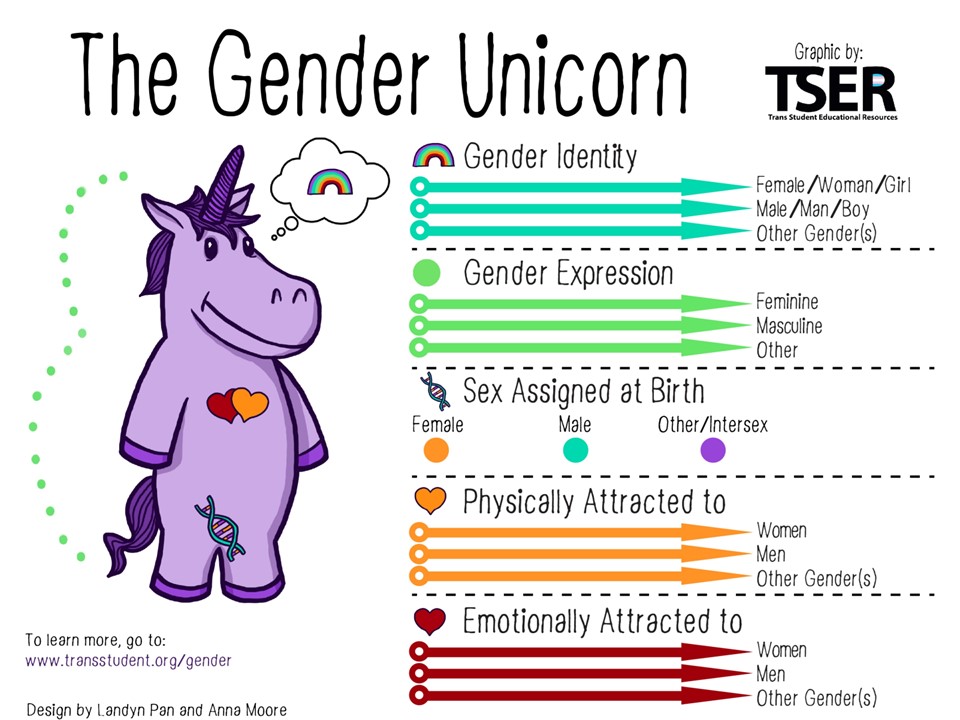

The LGBTQ community has a script to hand to confused people.[12] I present to you the Gingerbread Person:

Here’s a precis of the LGTBQ script:

- Your feelings are natural, good, and healthy.

- You need to discover “who you are,” and working out your true “gender identity”[13] is the key to your self-discovery.

- Your sexual attractions and/or inner feelings about your gender are the core of who you are as a person—it’s your identity!

- So, your sexual behavior and/or gender expression is the fruit of your identity.

- The only way you can be “true to yourself” is to live out that identity before the world

This is a very powerful script. If you’re a confused 15-year-old girl, what do you think she’ll find more compelling?

- Embrace sexual attractions or inner feelings to “discover who you really are?”

- Or, a guy with a “Footloose preacher” vibe: “God made Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve!”

The Better Story

Taking a strictly defensive “Alamo approach”[14] is the wrong way to respond. This includes (but is not limited to) sermons from Leviticus, amendments to the doctrinal statement to “protect” the church, and anger and rage a la Rev. Shaw.

The right way is to tell a different story; a better story! Identity is not about feelings as the pathway to self-discovery, but a choice about love and loyalty—will you follow your feelings or will you follow God?

What does God’s story say about identity? The best synopsis is from 1 Peter 2:9-11:

- You can be a part of something infinitely larger than yourself.

- Part of a chosen people.

- Part a royal priesthood to show and tell God’s story of love to the world.

- A citizen of a holy nation—one that transcends any nationalist loyalties from the here and now.

- Part of God’s special possession to tell about His mercy and love.

God came to rescue us from ourselves, give us a new name, a new family, a new heart, a new mind, and a better tomorrow. This identity is part of a story:

- God is making a community,

- thru Jesus the King,

- for His coming kingdom

You think the bible’s story is about salvation? Covenant? Kingdom? Promise? No—all these are waypoints in aid of something fundamentally simpler—a community, a restoration of the fellowship we were made to have with God and with each other.

This story has at least three plot moves:

- Creation. God made everything, and He made it good.

- Fall. Our first parents ruined it all, when Satan deceived them.

- Rescue. God’s plan to fix the mess, thru Jesus the King.

What place does Jesus offer us in this story?

- Identity—join me!

- Peace—reconciliation!

- Purpose—to be royal priests!

- Renovation—to remodel our hearts and minds to mirror His!

Tell the Better Story

Think with me, now—isn’t this such a different story than the LGBTQ script? Isn’t it such a better response than to only circle the wagons and preach angry sermons from Leviticus 18?

There is a concept in military strategy called “peer competitor,” which refers to an evenly matched geo-political foe. For example, China is a near peer competitor with the USA and some believe they will likely outmatch us within one or two generations.

The Footloose preacher is not a peer competitor to the LGBTQ script. He’s a babe in the woods, ranting at the sky—an artifact from very different era. He isn’t interested in telling the better story—only in the “purity” of his tribe.

But, the Christian story is more than a “peer competitor” to the LGBTQ script. It’s an alternative story—a better story. So, churches and their people must tell that story, persuade, make people think, beg them to see Jesus and His love.

We must give people real answers to real questions about a sexual or gender script that don’t feel they fit into very well. Basically, we need to tell the better story—the Gospel story.

For the sermon from this material, you can find the audio version here:

You can watch the sermon here:

[1] See also my sermon of the same title from 26 June 2022 at https://youtu.be/rSkL0WWhbDs.

[2] See “Trans Cathedrals: Beauty in Becoming,” (23 June 2022) on Middle Church’s (https://www.middlechurch.org/) YouTube channel at: https://youtu.be/_jy1YnrGK54.

“Cathedrals are trans bodies—beautiful and holy in every inch and in every moment of existence. They are beautiful and holy when they are first built, and beautiful when they are altered and edited, and they are beautiful and holy in the midst of that change. Even engulfed in scaffolding, even in the midst of a collapse. And their holiness and beauty is reflected in the lives of trans people—who do not only mimic the form of Christ on the cross but contain in their bodies the holiness of creation”

[3] Liam Coleman, “ AIR YOU JOKING? I’m turned on by planes and one day want to marry my toy Boeing,” The U.S. Sun. 30 May 2022. https://www.the-sun.com/news/5455665/turned-on-planes-marry/.

[4] See https://nypost.com/2022/05/31/woman-sexually-attracted-to-planes-wants-to-marry-toy-boeing/. This is a re-print of The U.S. Sun’s article, but it contains an additional photograph with the caption which I quoted.

[5] Ben Dooley and Hisako Ueno, “This Man Married a Fictional Character. He’d Like You to Hear Him Out,” New York Times. 24 April 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/24/business/akihiko-kondo-fictional-character-relationships.html.

[6] “Many Christians learned a mechanical, aggressive approach to evangelism. We attended workshops and read books based on techniques developed by people who have the gift of evangelism. That is the problem. When those of us who are not gifted evangelists muster up the courage to try these techniques, the results are usually disappointing—which makes us feel guilty and often offends others. We begin to think of ourselves as substandard disciples who are simply not able to share our faith. Although we want to see friends and colleagues come to Christ, we stop trying out of fear and frustration.

The problem is one of perspective, not inability. We tend to think of evangelism as an event, a point in time when we explain the gospel message and individuals put their faith in Jesus on the spot. Done!” (Bill Peel and Walt Larrimore, Workplace Grace: Becoming a Spiritual Influence at Work (Longview: LeTourneau Press, 2014; Kindle ed.), KL 196).

[7] Peel and Larrimore, Workplace Grace, KL 258.

[8] Thom S. Rainer, The Unchurched Next Door: Understanding Faith Stages as Keys to Sharing Your Faith (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2003; Kindle ed.), KL 863.

[9] See my sermon, “Cosmic Risk—The Parable of the Weeds.” 03 April 2022. https://youtu.be/RcBJnM9da1I?t=3251.

[10] Mark Yarhouse, Homosexuality and the Christian (Minneapolis: Bethany House, 2010), p. 46.

[11] The approach here is inspired most directly by Yarhouse, Homosexuality and the Christian, ch. 2. A good deal of what follows is from his work.

[12] See, for example, the latest discussion of the Gingerbread Person at https://www.genderbread.org/. See also the Gender Unicorn for a similar discussion, at https://transstudent.org/gender/.

[13] See “What is Gender Dysphoria?” at https://psychiatry.org/Patients-Families/Gender-Dysphoria/What-Is-Gender-Dysphoria.

[14] See my article “Christ, Culture, and the Church,” EccentricFundamentalist.com. 06 June 2022. https://eccentricfundamentalist.com/2022/06/06/christ-culture-and-the-church/.