In Romans 11, Paul finally answers the question he’s been dancing around since ch. 9: what is God’s plan for the people of Israel?

- He’s defended God against false accusations (Rom 9:6-29).

- He’s told us the nations have obtained righteousness from God, even though they didn’t pursue it. However, the people of Israel have come up empty. “But Israel, chasing after law as the means of righteousness, didn’t achieve that goal. Why not? Because they’re chasing righteousness not by means of faith, but as if by means of works,” (Rom 9:31-32; my translation).

- Paul explained: “… because they don’t know the special righteousness which God offers and are trying to set up their own righteousness, they haven’t submitted themselves to this one-of-a-kind righteousness from God,” (Rom 10:3; my translation).[1]

So, in Romans 11, Paul at last answers the question. But we’re making a mistake if we reduce this to an academic question about “Israel.” The real question is: “how will God’s divine rescue plan come together?” Christians sometimes have incomplete ideas about this—they either ignore His promises to the people of Israel or maximize those promises and lose sight of the whole. So, how will God’s plan come together, and what will it look like when it’s finished?

1. God hasn’t rejected the people of Israel (vv. 11:1-6)

God has not rejected His people.[2] Perhaps a better translation is “repudiate,”[3] which gives the idea of to thrust or drive away[4]—to cast off, disown, to refuse to be associated with.[5] How could God have disowned His people if Paul himself is a native Israelite (Rom 11:1)? God has known the people of Israel for a long time[6]—He has a relationship with them (Rom 11:2). It is not over for them.

So, what’s happening, then? Why have the people of Israel not accepted Jesus as their Messiah? Does God intend to rescue (a) all the people of Israel, or (b) a group from within the larger number?

Paul explains that, for the moment, God is working through a remnant. Just as He reserved a small core of people for Himself during the prophet Elijah’s day, “[s]o too, at the present time there is a remnant chosen by grace,” (Rom 11:5). And, then and now, these are people God has reserved for Himself—salvation is ultimately the result of God’s specific grace(Rom 11:4).[7] Whatever God is up to, for right now He’s only rescuing a smaller group of Jewish people.

This rescue is by means of grace, not by means of works[8]—or else it wouldn’t be called “grace” (Rom 11:6). This is what the people of Israel had missed (Rom 9:30 – 10:4). If I owe you money, when I pay you it’s not an expression of love or friendship—it’s a business transaction. With God, His divine favor and love is a gift, not a business transaction.

2. Instead, God is punishing the people of Israel (vv. 11:7-10)

So, if God hasn’t repudiated the people of Israel, what is He doing with them?

The people of Israel had chased after righteousness but missed the boat. The chosen ones among them had made it, “but the others were hardened,” (Rom 11:7). The idea here is a divine blinding, a veil of sorts, a darkening of the mind—a mental block that makes them “not get it.”[9]

This is a punishment which follows the failed chase—“God permits them to become entangled in their own No.”[10] If God is God, then He has the power to act upon our hearts and minds so that we make real, voluntary decisions, but in the manner He wants (cp. Jn 12:39-40). God channels our desires towards the goal He’s determined. This is not a new thing:

- When Moses preached to the people of Israel on the eastern banks of the Jordan River, he recounted Israel’s long and sad tale of disobedience. Paul quotes Moses here in support: “God gave them a spirit of stupor, eyes that could not see and ears that could not hear, to this very day,” (Rom 11:8; quoting Deut 29:4).

- King David called out to God in misery and asked for judgment on his enemies: “May the table set before them become a snare; may it become retribution and a trap. May their eyes be darkened so they cannot see, and their backs be bent forever,” (Rom 11:9-10; quoting Ps 69:22-23).

Paul says the same thing has happened to the people of Israel. God hasn’t repudiated or disowned them—He’s punishing them.

3. What’s the point of God’s punishment? (vv. 11:11-32)

Paul writes:

So, I’m asking: “they didn’t stumble and ruin themselves, did they?” May it never be! Instead, because of their false step, the divine rescue [goes] to the nations, so that it will make the people of Israel jealous.[11]

Romans 11:11; my translation

There you have it. Israel’s “false step” or “trespass—their rejection of Christ as the long-promised prophet, rescuer, and king—triggers God’s pivot to the nations. God is making the people of Israel jealous, envious (cp. Rom 10:19). Interestingly, Paul’s focus is not the nations per se. Instead, he frames the people of Israel as the hinge upon which God’s whole rescue plan turns.[12] The idea is that the people of Israel will see God showing love + grace to the nations, become jealous, re-evaluate, then choose divine rescue through Jesus.

This obviously hasn’t yet happened. Right now, the people of Israel either (a) don’t care, or (b) reject Christ. The people of Israel will never become jealous unless they first agree that Jesus is their Messiah. For example, one kid won’t be jealous of the other’s cookie unless they both agree the cookie is worth having! I’m not jealous if my wife eats plain Lays potato chips, because I don’t like plain Lay’s potato chips.

So, when will God change their minds and make the people of Israel jealous, so they’ll want Jesus as their king, too? During the Millennium (see Zech 12:10ff). But Paul ignores this question—he homes in on “the nations” who will read his letter. He deploys a sort of parable to explain God’s divine rescue plan.

3.1. The parable of the olive tree (vv. 11:13-24)

Paul is the apostle to the nations. But, along the way, he hopes to “somehow arouse my own people to envy and save some of them,” (Rom 11:14). Remember that, for the moment, God is saving a remnant of the people of Israel and Paul aims to scoop some of them up as he goes along. He declares “if the root is holy, so are the branches” (Rom 11:16). That is, if the people of Israel are the channel for all the covenants, the patriarchs, the promises (Rom 9:3-5)—i.e., “the root” of the Christian family—then surely the “branches” downstream of the patriarchs (the people of Israel alive in this present age) have a future, too.[13] Their restoration will be like a resurrection from the dead (Rom 11:16)!

Paul now segues into the olive tree parable:

If some of the branches have been broken off, and you, though a wild olive shoot, have been grafted in among the others and now share in the nourishing sap from the olive root, do not consider yourself to be superior to those other branches.

Romans 11:17-18

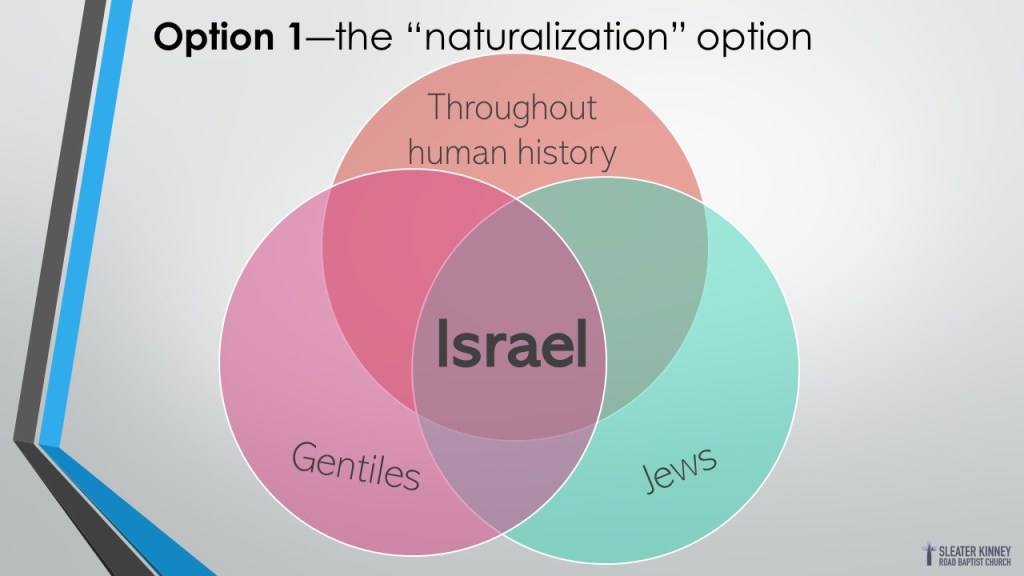

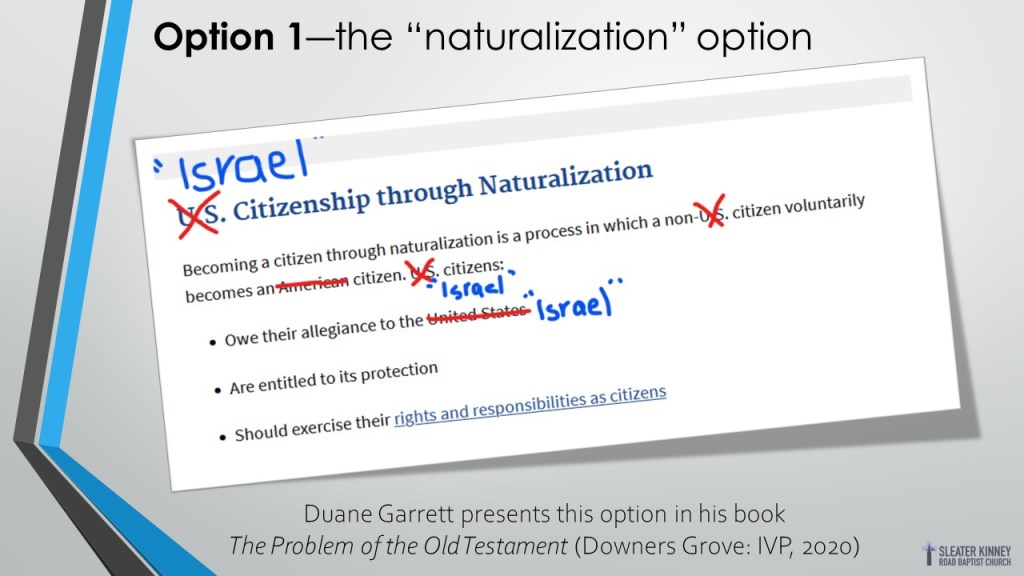

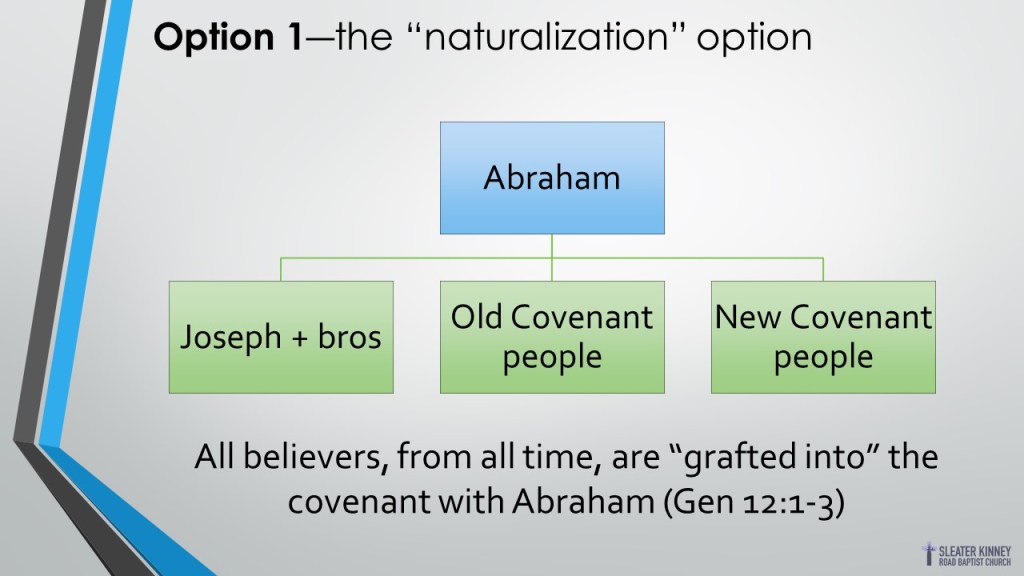

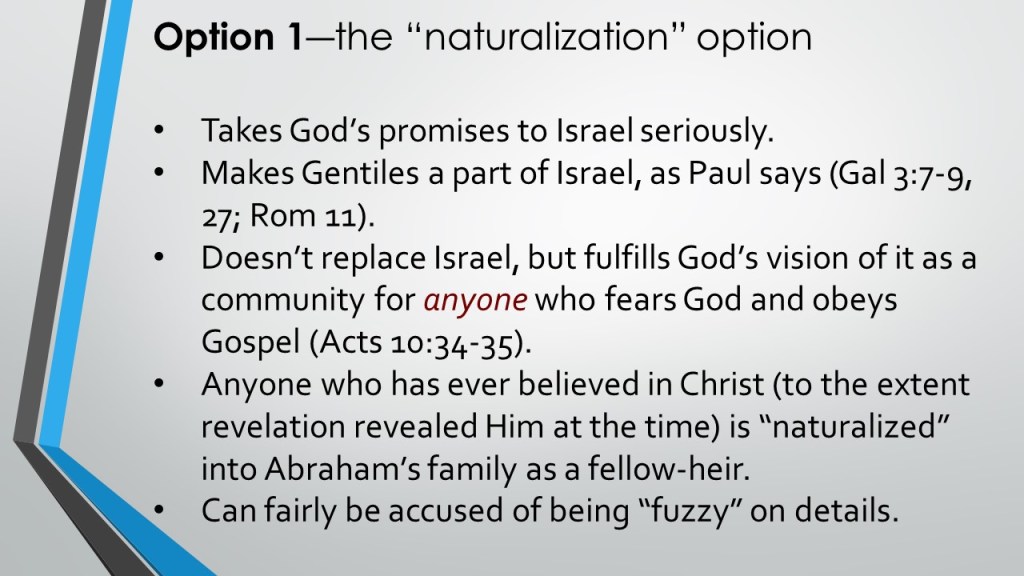

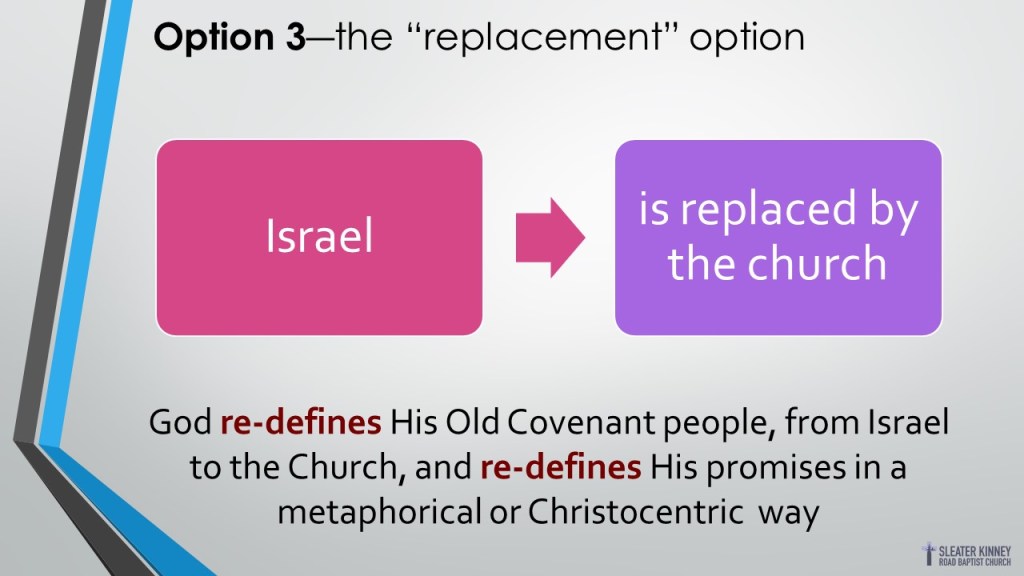

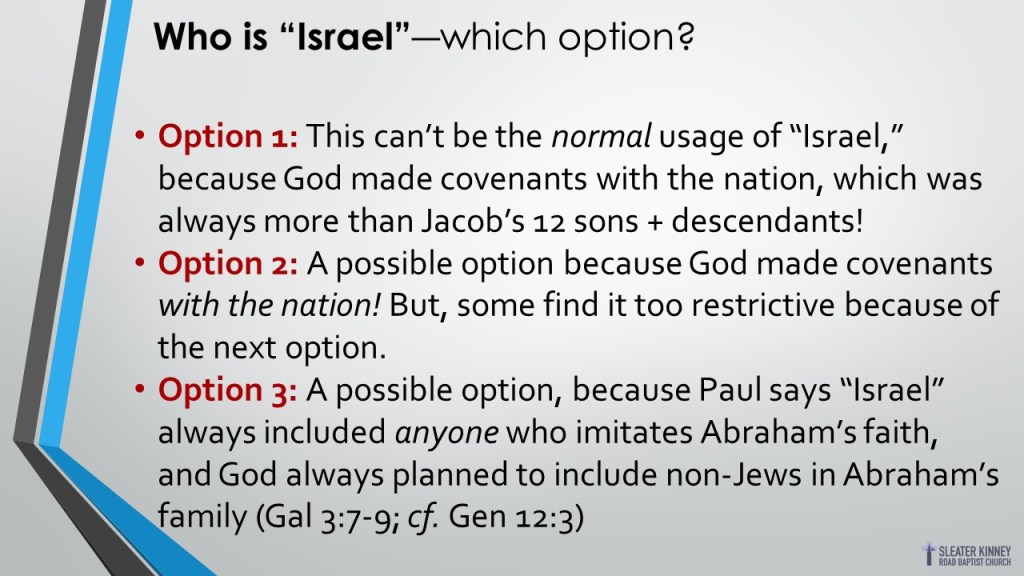

God has broken some of these downstream Israelite “branches” off, and grafted non-native “olive shoots” into the tree. They “now share in the nourishing sap from the olive root.” This is not a substitution or a replacement—it is an unexpected addition. Both (a) the native branches which remain, and (b) the non-native branches which God has added to the tree, partake of the same nutrients from the same root. “The Gentiles nourish themselves on the rich root of the patriarchal promise”[14] because, as the apostle writes elsewhere, “if you belong to Christ, then you are Abraham’s seed, and heirs according to the promise,” (Gal 3:29).

Because these new “olive shoots” are non-native, they mustn’t become arrogant. “You will say then, ‘Branches were broken off so that I could be grafted in,’” (Rom 11:19). This is true, but the people of Israel were “hardened” or “blinded” (i.e., branches cut off from the tree) because of their unbelief. In contrast, the nations (i.e., the non-native olive shoots) only remain “in” this tree and stand firm because of faith. Faith is the determining factor, so “[d]o not be arrogant, but tremble,” (Rom 11:20).

If you ever get to the point that you think your relationship with God is because of who you are, what you’ve done, what you bring to the table—that it’s about something other than faith + trust in Jesus (Rom 11:20)—then you’ll be cut out of the tree just as surely as the people of Israel have been (Rom 11:22).

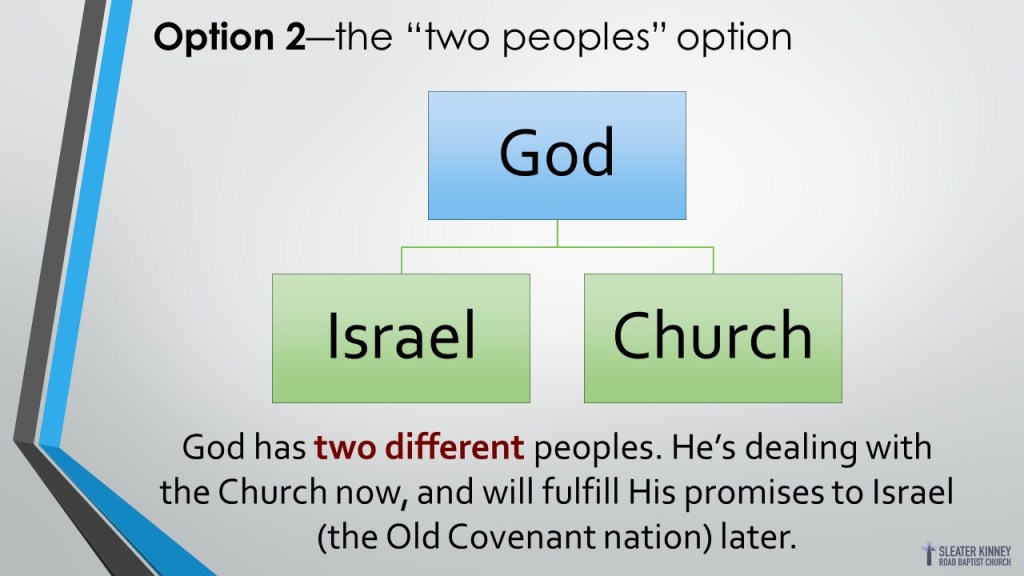

The players in the parable are now clear:

One olive tree → One family of God

Two types of branches on this tree → Two different people groups within God’s family

There is (a) one family of God, (b) from two different places, (c) drawing on the same Lord, the same faith, the same baptism (Eph 4:5; i.e., the same sap). There is one flock, governed by the same shepherd and king. There is the same divine rescue, the same love, the same grace, the same forgiveness. This is the secret or mystery which has now been revealed by the Holy Spirit to God’s apostles and prophets: “the secret is that, through the Good News, the nations are fellow-heirs, and united in one family, and sharers together in God’s promise in relationship with Christ Jesus,” (Eph 3:6, my translation).

- Jesus spoke of “other sheep” that were not native to His flock: “I must bring them also. They too will listen to my voice, and there shall be one flock, and one shepherd,” (Jn 10:16).

- John wrote that the high priest Caiphas spoke better than he knew when he suggested it would be for the greater good if they killed the troublesome Jesus: “[H]e prophesied that Jesus would die for the Jewish nation, and not only for that nation but also for the scattered children of God, to bring them together and make them one,” (Jn 10:51-52). This refers to the nations.

- The prophet Isaiah records the words of the mysterious “suffering servant” as he recalls Yahweh’s instructions. It wasn’t enough for the Servant to just rescue the people of Israel: “I will also make you a light for the Gentiles, that my salvation may reach to the ends of the earth,” (Isa 49:6).

This means Paul’s olive tree parable is a restatement of an old promise in new clothes. And to be sure, it’s not over for the people of Israel (cp. Rom 11:11)—“if they do not persist in unbelief, they will be grafted in, for God is able to graft them in again,” (Rom 11:23).

3.2. This parable means the people of Israel have a future (vv. 11:25-32)

Paul is using the parable of the olive tree to explain God’s rescue plan—how does the tree come to its finished form? It will be a three-step process:

I do not want you to be ignorant of this mystery, brothers and sisters, so that you may not be conceited: Israel has experienced a hardening in part until the full number of the Gentiles has come in, and in this way all Israel will be saved.[15]

Romans 11:25-26

It’s never been a secret that God plans to rescue His people. What has been a secret is the specific way this rescue plan happens. Paul doesn’t want the nations to be in the dark any longer, else they might become arrogant and think themselves wiser than they are. Here, Paul writes, is the mystery:

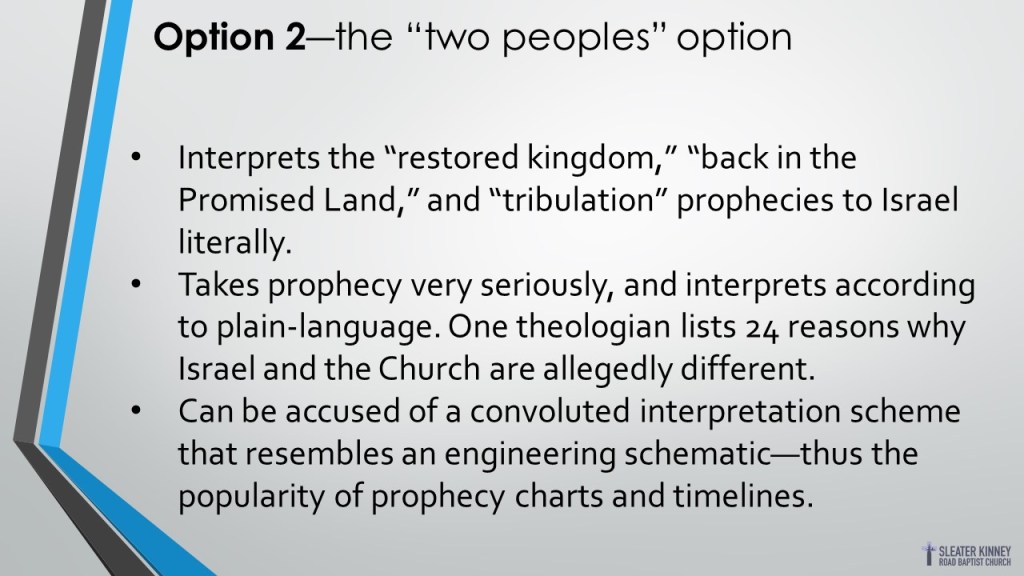

- First, the most people of Israel do not believe God’s good news of righteousness as a gift, by means of faith. Instead, they choose to pursue it by means of “resume-ism.” So, this majority of Israelites are the branches whom God has “broken off” and to whom He’s temporarily sent “blindness” and “hardness of heart”—a dullness of spirit.

- So, second, God has now pivoted to the nations and to the Jewish remnant—the “wild olive shoots” are being grafted into the tree. This present stage of God’s rescue plan will last “until the full number of the nations have entered in” and joined God’s kingdom family, at which time God lifts the divine “blindness” and rescue operations will proceed for the people of Israel.

- And so, third, this is how “all Israel will be rescued.”

The “all Israel” refers to the ethnic Jewish people who are alive at the time God moves to the third stage, after the full number of the nations have entered the family.[16]

- It cannot mean “every Jewish person who ever lived.” God isn’t a universalist (even at the sub-category level), and it would be absurd to suppose Caiphas will be walking the streets of glory.

- Paul isn’t referring to a re-defined “Israel” consisting of all true believers (cp. Gal 3, 6:16; Rom 4). His focus here in Romans 9-11 is ethnic Jewish people.

- He isn’t referring to all “true” ethnic Jewish people from all time, because Paul’s burden in Romans 9-11 is to explain what’s happening to the people of Israel right now in relation to His divine timetable.

But, through it all, it’s still the same Jesus, the same king, the same divine rescue mission. Two people groups merged into the same family, the same tree, partaking of the same “sap.” God has not pushed away the people of Israel—there is (a) the remnant which can meanwhile choose to pursue God by means of faith, and (b) the entire number of Jewish people who will embrace Jesus as Messiah after the full number of the nations have come in. The people of Israel “are loved on account of the patriarchs, for God’s gifts and his call are irrevocable,” (Rom 11:28-29).

This three-stage rescue plan, culminating in God rescuing all the ethnic people of Israel then alive when Christ returns, is just what scripture foretold (“as it is written,” Rom 11:26). The prophet Isaiah tells us that one day the Lord looked about and saw the human situation was hopeless—that He Himself must enter the arena to set things right. “So his own arm achieved salvation for him, and his own righteousness sustained him,” (Isa 59:16). And so the Redeemer would one day come to Zion—“to those in Jacob who repent of their sins” (Isa 59:20). The covenant Yahweh swore to make with His people would take away their sins, because “My Spirit, who is on you, will not depart from you,” (Isa 59:21). The apostle quotes the former citation and paraphrases the latter as support for a future for the people of Israel (Rom 11:26b-27).

4. One God and father of all

Paul never again probed so far behind the divine curtain. The see-saw of God’s rescue plan—Israel, then the nations, then Israel again (Rom 11:12, 30-32)—overwhelms him. “How unsearchable his judgments, and his paths beyond tracing out!” (Rom 11:33).

Commentators have spilt gallons of ink and gigabytes of megapixels on interpreting this passage—especially Romans 11:25-26. What is clear is that the people of Israel have a future. It’s not a “blank cheque” future which encourages a laissez-faire life of spiritual fakery. Nor is it a “I’ll never get tickets to the show!” kind of defeatism that one has when trying to purchase Taylor Swift concert tickets. There will be more than a “lucky few” Israelites grafted back into God’s olive tree! It is a real future—(a) the remnant chosen by grace now, followed by (b) “all Israel” present here when Christ returns later.

Yes, God has unfinished business with Israel during the Millennium, but that is merely the last stop before journey’s end. The “Israel maximizers” make a mistake if they hop off the train here,[17] because there is yet one more stop to go. The train decommissions in Revelation 22, when there will be one family, one tree, “one God and Father of all, who is over all and through all and in all,” (Eph 4:6). God will restore Eden, and the tree of life will be available to all “for the healing of the nations” (Rev 22:1-5).

Of course, Paul doesn’t discuss that here. But the people of Israel will be there … along with all the other nations who are blessed through Abraham (Gal 3:8) and have become His offspring.

[1] Gk: ἀγνοοῦντες (adverbial, causal) γὰρ (explanatory) τὴν (monadic) τοῦ θεοῦ (gen. source) δικαιοσύνην καὶ τὴν ἰδίαν (δικαιοσύνην) ζητοῦντες (adverbial, causal—paired with ἀγνοοῦντες) στῆσαι (BDAG, s.v., sense 3; anarthrous, complementary), τῇ δικαιοσύνῃ (monadic) τοῦ θεοῦ (gen. source) οὐχ ὑπετάγησαν (passive w/middle sense, constative).

[2] The fact that the people of Israel are “his people” (τὸν λαὸν αὐτοῦ; Rom 11:1) is significant.

[3] BDAG, s.v. “ἀπωθέω,” sense 2; p. 126.

[4] LSJ, s.v. “ἀπωθέω,” senses 1, 2; p. 232.

[5] OED, s.v. “repudiate,” senses 1a, 2a.

[6] It goes too far to plead that “foreknow” here (προέγνω) means something like “to choose beforehand.” The word can bear that meaning (e.g. 1 Pet 1:20), but the more common use is just “to know beforehand or in advance” (BDAG, s.v., sense 1, p. 966) or to “foreknow” (LSJ, s.v., sense 3). Reformed exegetes who wish to carry water for unconditional single election will find fertile ground elsewhere in scripture, but Romans 11:2 is not the place to plant that flag.

[7] The 1833 New Hampshire Confession explains: “… regeneration consists in giving a holy disposition to the mind; that it is effected in a manner above our comprehension by the power of the Holy Spirit, in connection with divine truth, so as to secure our voluntary obedience to the gospel,” (Article VII).

[8] Gk: εἰ δὲ χάριτι (dative of means), οὐκέτι ἐξ (means) ἔργων.

[9] See BDAG, s.v. “πωρόω,” and LSJ, s.v., sense 3.

[10] Emil Brunner, The Epistle to the Romans, trans. H.A. Kennedy (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1959), p. 94.

[11] Λέγω οὖν, μὴ ἔπταισαν (fig. for “sin”) ἵνα πέσωσιν (result clause; BDAG, s.v., sense 2b); μὴ γένοιτο· ἀλλὰ τῷ αὐτῶν (dir. obj) παραπτώματι (dat. reason) ἡ σωτηρία (monadic article) τοῖς ἔθνεσιν (implied verb of “going,” dir. obj.) εἰς τὸ παραζηλῶσαι (purpose clause) αὐτούς (dir. obj. of infinitive—refers to people of Israel).

[12] John Murray, The Epistle to the Romans, vol. 2 (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1965), p. 76.

[13] Leon Morris, The Epistle to the Romans (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1988), pp. 411-412.

[14] Brunner, Romans, p. 96.

[15] Gk: Οὐ γὰρ θέλω ὑμᾶς ἀγνοεῖν, ἀδελφοί, τὸ μυστήριον τοῦτο (dir. obj.), ἵνα μὴ ἦτε (purpose clause) παρʼ ἑαυτοῖς φρόνιμοι. ὅτι (appositional—explains the mystery) πώρωσις ἀπὸ μέρους (paired to τῷ Ἰσραὴλ) τῷ Ἰσραὴλ (dative of reference) γέγονεν ἄχρι οὗ τὸ πλήρωμα τῶν ἐθνῶν (partitive) εἰσέλθῃ 26 καὶ (conclusion) οὕτως (adverb of manner) πᾶς Ἰσραὴλ σωθήσεται, καθὼς γέγραπται.

“Now, I don’t want you all to be in the dark about this secret, brothers and sisters, so that you won’t think you’re wiser than you are. The secret is that a dullness of spirit has come upon some of the people of Israel until the full number of the nations have entered in. And so, that is how all Israel will be rescued …”

[16] “… Paul speaks of a future salvation of ethnic Israel near or at the return of Jesus Christ,” (Tom Schreiner, Romans, in BECNT, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2018), pp. 598ff). See also Douglas Moo, The Epistle to the Romans, in NICNT (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1996), p. 723.

[17] Tom Schreiner rightly warns: “The purpose of this revelation is not to titillate the interest of the church or to satisfy their curiosity about future events. The mystery is disclosed so that the gentiles will not fall prey to pride …” (Romans, p. 595).