We continue our look at the great prophecy of Daniel 9:24-27. Read the rest of the series.

Now we come to the fun part of this prophecy. Some of the details from the sweeping vision of Daniel 9:24 will now be spelled out. Daniel wants to know when God will bring his people back from exile and restore his kingdom that has fallen. So, Gabriel gives him God’s answer:

So you are to know and understand that from the issuing of a decree to restore and rebuild Jerusalem, until Messiah the Prince, there will be seven weeks and sixty-two weeks; it will be built again, with streets and moat, even in times of distress (Daniel 9:25).

There are two big events in Daniel 9:25: (a) the decree “to restore and rebuild Jerusalem,” and (b) Messiah the prince’s arrival on the scene. Fair enough. But there is controversy about how to translate this passage. I mention this because your bible translation may differ from the NASB (2020) which I’m using in this article.

- Option 1 suggests (a) Messiah’s arrival = seven “sevens,” and (b) Jerusalem’s re-building = 62 “sevens”—a total of 69 “sevens” (ESV; also RSV, NEB, REB, CEB, NRSV).

- Option 2 says (a) Messiah’s arrival, and (b) the rebuilding of Jerusalem = 69 “sevens.” The specific timeframes of each are undefined (NASB; also NLT, NET, KJV, NIV, CSB).

You can see the difference in these two examples:

Many good Christians are on each side of this translation issue.[1] Regardless, it’s clear that by the end of the 69 “sevens” Messiah will have arrived on the scene, and Jerusalem will have been re-built. In Daniel’s day, Jerusalem lies in ruins (Lam 5:17-18). Although Daniel couldn’t have known this at the time, bible history tells us that first the exiles returned and rebuilt the city and its temple, and then Messiah arrived on the scene in the opening pages of the New Covenant scriptures. So, it’s best to understand these events as being keyed to the two time-periods, so the 69 “sevens” shake out like this:[2]

At the end of these 69 “sevens” (more on that in a minute), both these events will have happened.

Or have they?

Some otherwise solid bible teachers say that Jerusalem’s “rebuilding” is really about the “spiritual kingdom” of God advancing in the world.[3] This unlikely. There’s no good reason to dismiss the straightforward interpretation that Jerusalem means Jerusalem here—Daniel is talking about the actual city being truly rebuilt.

Of course, that’s exactly what happened. The city and its walls and its temple were rebuilt, “even in times of distress” (Dan 9:25)—just as Gabriel said it would be. Later, in Nehemiah 4:11, the bible tells us about these troublesome times as they tried to re-build the city in the years after Ezra led people back to Israel: “And our enemies said, ‘They will not know or see until we come among them, kill them, and put a stop to the work.’”

What are the “sevens”?

The word your bible may translate as “weeks” means “sevens” (שִׁבְעִ֜ים), which is a vague time marker that context must explain. Sometimes it means years (Dan 9:3). Sometimes it doesn’t. This “sevens” business is weird—why does God communicate to Daniel this way?

The simplest explanation is that God is riffing off the “70 years (שִׁבְעִ֜ים) of captivity before I bring you back to the promised land” thing which promoted Daniel to pray in the first place (see Dan 9:2; cp. Jer 25:11-12, 29:10). That is, God is basically saying:[4]

- “Yes, Daniel, you’re right—70 “sevens” (שִׁבְעִ֜ים) will elapse before I start to bring y’all back to the promised land.”

- “But, 70 other “sevens” (שִׁבְעִ֜ים) will elapse before I really, truly fix the root problem.”

And it’s the end of these 70 “sevens” that brings us to paradise in the better tomorrow (Rev 20:21-22).

So, what are the 70 “sevens” from our prophecy in Daniel 9:24-27? We should interpret the bible plainly unless there is reason not to do so. Again, the word your bible may translate as “weeks” means “sevens” (שִׁבְעִ֜ים), which is a vague time marker that context must explain. There are 70 “sevens” or “units of [something]” in this entire prophecy (Dan 9:24). Here are four common options:

- 70 sets of days (70 days).

- 70 sets of years (70 years).

- 70 sets of seven years (490 years).

- 70 symbolic numbers that have no literal sense of time.

How do we know how to understand these “sevens?”[5] The clearest measure is the 69 “sevens” that elapse from (a) the order to rebuild Jerusalem, until (b) the anointed one (“Messiah”) arrives. However long this time is, it equals 69 “sevens.” So, if we figure out this time-period, we can figure out what a “seven” is. You must first determine the date of one of these two events—the beginning point is the decree to restore and rebuild Jerusalem, and the end point is Messiah’s arrival.

- Don’t start at the beginning! Many bible teachers (and students!) drown in dates and charts at this point because they try to first determine the date of the decree to rebuild Jerusalem. This is not a good place to start. There are at least four plausible options in the old covenant scriptures, and it all becomes very complicated.

- So, if there is an easier option to figure this out, we ought to take it and run with it.

- Fortunately, there is a better option. It’s simpler to begin with the end point (the arrival of Messiah, the prince/ruler) and then work backwards.

- This date is easier—there is comparatively little debate among bible-believing interpreters about the date of Jesus’ arrival on the scene.

So, we will take the best date(s) for the beginning of Jesus’ ministry (i.e., his “arrival”)[6] and work the 69 “sevens” backwards from there, using each of the four possible “ways” to understand the “sevens” (above). Here is how we do it:[7]

- I interpret Jesus’ arrival (“until Messiah the Prince”) as his baptism, when his ministry formally kicks off (Mk 1:9-13). If you try to use Christmas as his arrival, no calculation makes any sense at all. So, the baptism it is.

- It’s very likely the Romans crucified Jesus in April of A.D. 30. Some say A.D. 33. I assume A.D. 30 in the calculations that follow.[8]

- By counting the number of Sabbaths mentioned during Jesus’ ministry, we determine his ministry probably lasted about 3.5 years.[9]

- This would put Jesus’ arrival on the scene (his baptism) as late A.D. 26 (i.e., April, A.D. 30 minus 3.5 years = October-ish, A.D. 26).

- We can now count backward using the various “69 units of something” options to figure out the most likely solution.

There are 69 “units of something” from the decree to rebuild Jerusalem until A.D. 26, when the Messiah who is a prince/leader/ruler arrives.

- Option 1—A.D. 26 minus 69 units of days (69 days). This would put the decree to rebuild Jerusalem at 69 days before Jesus’ baptism at Mark 1:10-11. This option clearly doesn’t work. The city was rebuilt long before this point!

- Option 2—A.D. 26 minus 69 units of years (69 years). This would put the decree to rebuild Jerusalem as happening in 43 B.C. This isn’t true—the returning exiles rebuilt Jerusalem by at least 445 B.C. (Neh 6:15)!

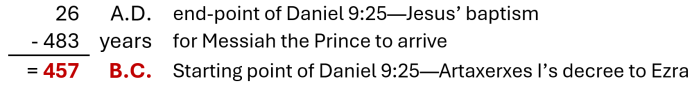

- Option 3—A.D. 26 minus 69 units of seven years each (483 years). This would put the decree to rebuild Jerusalem as happening in 457 B.C (that is, A.D. 26 minus 483 years). This option fits well with Ezra’s commission to go to Jerusalem and establish God’s community in the city, now that the temple had been built—see Ezra 7:12-26; 9:9.

The Israelite’s return from the east to the promised land didn’t happen all at once. It came in fits and starts. The issues involving these dates are complicated. I’ll use generally accepted dates from conservative sources.[10]

- Some folks, like Esther and her family, chose not to return to the promised land at all.

- 538-ish B.C. Many Jews returned when Cyrus, the Persian ruler, gave them money, supplies, and allowed them to return and rebuild the temple in 538 B.C. (Ezra 1-6).[11] This is a tale also told in the books of Haggai and Zechariah.

- 457 B.C. The next wave of exiles returned to the promised land under the leadership of Ezra, the priest (Ezra 7),[12] with the blessing of the Persian ruler, Artaxerxes I.

- 445 B.C. About twelve years after Ezra and his party left for Jerusalem to the west, Nehemiah in Persia hears a report about how the city still lies in ruins and is yet to be fully repaired: “… the wall of Jerusalem is broken down and its gates have been burned with fire” (Neh 1:3). He seeks for and receives permission from the Persian ruler, still Artaxerxes I, to go (Neh 2:1-8).

Returning to our options for dating—the only reasonable solution, if we take each “seven” to be a unit of seven years each, is to see the beginning point of the timespan from Daniel 9:25 as Artaxerxes I’s decree for Ezra to head to Jerusalem in ≈ 457 B.C. It shakes out like this:

- The end point (“until Messiah the prince,” Dan 9:25) is Jesus’ baptism in A.D. 26.

- 69 “units of seven years each” = 483 years.

So …

Again, this fits well with Artaxerxes I’s decree for Ezra to head to Jerusalem in ≈ 457 B.C. Nevertheless, some good Christians disagree:

- Some good bible scholars protest that, when the Persian king gave Ezra permission to go to Jerusalem sometime after the first wave of exiles had already returned (Ezra 7:12-26), the city was already in the process of being rebuilt.[13] They claim that the first wave of exiles who returned ≈ 538 B.C. already began this work.

- After all, the foreigners in the land wrote to the Persian king before Ezra set out, complaining that “the Jews who came up from you have come to us at Jerusalem; they are rebuilding the rebellious and evil city and are finishing the walls and repairing the foundations” (Ezra 4:12).

What shall we do with this data?

- First, the 457 B.C. date just works. It does. It works perfectly. So, if there is a reasonable solution that lets us keep the date, we should grab hold of it.

- Second, it is true that Artaxerxes did not specifically tell Ezra to rebuild the city. But, he did send Ezra out to organize the returned exiles into a proper community and establish religious order. Ezra was apparently to be a sort of priest/governor: “And you, Ezra, according to the wisdom of your God which is in your hand, appoint magistrates and judges so that they may judge all the people who are in the province beyond the Euphrates River, that is, all those who know the laws of your God; and you may teach anyone who is ignorant of them” (Ezra 7:25). Ezra understood that his job included rebuilding the ruined city: “to give us reviving to erect the house of our God, to restore its ruins, and to give us a wall in Judah and Jerusalem” (Ezra 9:9).

- Third, in the mid-440s B.C. when Nehemiah arrived on the scene, the city was still in ruins. “I was inspecting the walls of Jerusalem which were broken down and its gates which had been consumed by fire (Neh 2:13). He told his companions what he’d discovered: “Jerusalem is desolate and its gates have been burned by fire” (Neh 2:17). Working like madmen amidst fierce opposition, the city walls were only fully re-built in 445 B.C. (Neh 6:15; see also Neh 3-5).

- Fourth, Ezra’s failure to finish rebuilding the city and its walls in the ≈ 12 years before Nehemiah pulled into town doesn’t nullify the Ezra option. It just means Ezra’s time was monopolized with other matters.[14]

- Fifth, this all suggests the foreigners who wrote that letter to the Persian ruler were lying. The first wave of returned exiles rebuilt the temple in 515 B.C. (Ezra 6:15).[15] But the city was still a mess. A wasteland. Nehemiah tells us so. The folks who wrote that letter had their own reasons—they feared the Jewish people would establish themselves back in the promised land. So, they exaggerated the Jewish people’s progress and imputed sinister motives to them (Ezra 4:13-14) so the Persian king would order a halt to the whole thing. They succeeded (Ezra 4:17-24).

So, the decree to Ezra in ≈ 457 B.C. still makes good sense, which means each “seven” = a unit of seven years. Further, God advised the Israelites that the promised land, which they had defiled, must enjoy the sabbaths the people had ignored for 70 years (2 Chr 36:21). He also warned his people that he would repay them seven-fold for their sins (Lev 25:18, 21). This seems to be the springboard for Gabriel’s 70 “sevens” in our prophecy. The 70 “sevens” of punishment in captivity times 7x for their sins = 490 years = the 70 “sevens” at Daniel 9:24.[16]

All this indicates there is no need to consider the last option for understanding the “sevens”—the symbolic one. So, we have an incredibly detailed prophecy from Daniel 500-ish years before the events occurred—down to the very month of Jesus’ baptism. Gabriel clearly tells Daniel that, 483 years from a future decree to restore and re-build Jerusalem, the city will be rebuilt in times of trouble, and the Messiah will have arrived on the stage.

More details will come in Daniel 9:26, in the next article.

[1] For example, C.F. Keil and Franz Delitzsch spend a great deal of time defending the option that the ESV translation later represented (Commentary on the Old Testament, vol. 9 (reprint; Peabody: Hendrickson, 1996), 729). But, in the end, they agree that by the end of the 69 “sevens” Messiah will have arrived and Jerusalem will have been rebuilt. So, in a sense, the translation difference does not matter—the whole thing will take 69 “sevens.” But, it begins to matter when you try to sort the two events into order.

[2] “… the true reason of the 69 weeks being divided into seven, and 62, is on account of the particular and distinct events assigned to each period …” (Gill, Exposition of the Old Testament, 6:346).

[3] Leupold, Daniel, 424-25.

[4] Moses Stuart writes: “Daniel’s meditation had been upon the seventy simple years predicted by Jeremiah. The angel tells him that a new-seventy, i.e. seventy week-years or seven times seventy years, await his people, before their final deliverer will come” (Daniel, 266; emphases in original).

[5] A brief, reasonable defense of the “seven = one unit of seven years each” and the ≈ 457 B.C. date, which I propose here, is from Gleason Archer, “Daniel,” in Expository Bible Commentary, vol. 7, ed. Frank Gaebelein (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1985), 113-16.

[6] If we reckon Messiah’s “arrival” as Christmas morning, then no option but the symbolic one works for the “sevens.” I do not discuss this “arrival = Messiah’s birth” option here, but you ought to know it is an option. Instead, I take Messiah’s arrival to be the start of his ministry—his baptism.

[7] There are two dating calculations computed by the best bible-believing scholars: (a) the A.D. 26 date for Jesus beginning his ministry at his baptism + the A.D. 30 date for his crucifixion (≈ 3.5 years of ministry), or (b) an A.D. 30 date for the beginning of his ministry + the A.D. 33 date for his crucifixion (also ≈ 3.5 years of ministry).I believe Option A is correct, largely based on this prophecy from Daniel and because the calculations are defensible.

These calculations are extraordinarily technical. See (a) Jack Finegan, Handbook of Biblical Chronology, revised ed. (Peabody: Hendrickson, 1992), §581, §583-4; §615-20, and (b) Harold Hoehner, Chronological Aspects of the Life of Christ (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1977), ch. 3, 5.

[8] Finegan, Biblical Chronology, §629 and references therein. Finegan opts for A.D. 33, but his analysis shows A.D. 30 is also quite probable.

[9] “Three years plus a number of months” (Finegan, Biblical Chronology, §628, §600-601).

[10] An excellent overview is Leon J. Wood, A Survey of Israel’s History, rev. David O’Brien (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1986), 333-41.

[11] This happened in “the first year of Cyrus king of Persia” (Ezra 1:1), which was 539 B.C. (Jason Silverman, s.v., “Cyrus II,” in The Lexham Bible Dictionary, ed. John D. Barry et al. (Bellingham: Lexham Press, 2016)).

[12] This occurred “in the seventh year of the king” of Persia, Artaxerxes I (Ezra 7:1, 8). This was about 457 B.C. (Walter A. Elwell and Barry J. Beitzel, “Artaxerxes,” in Baker Encyclopedia of the Bible (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1988), 207).

[13] Edward Young, The Prophecy of Daniel (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1949), 202-3; Andrew Steinmann, Daniel (St. Louis: Concordia, 2008), 462, 470.

[14] Archer, “Daniel,” in EBC, 7:114.

[15] For the 515 B.C. date, “[n]ow this temple was completed on the third day of the month Adar; it was the sixth year of the reign of King Darius” (Ezra 6:15), see Paul L. Redditt, s.v., “Temple, Zerubbabel’s,” in Lexham Bible Dictionary).

[16] Joyce G. Baldwin, Daniel, vol. 23, in Tyndale Old Testament Commentaries (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 1978), 187.