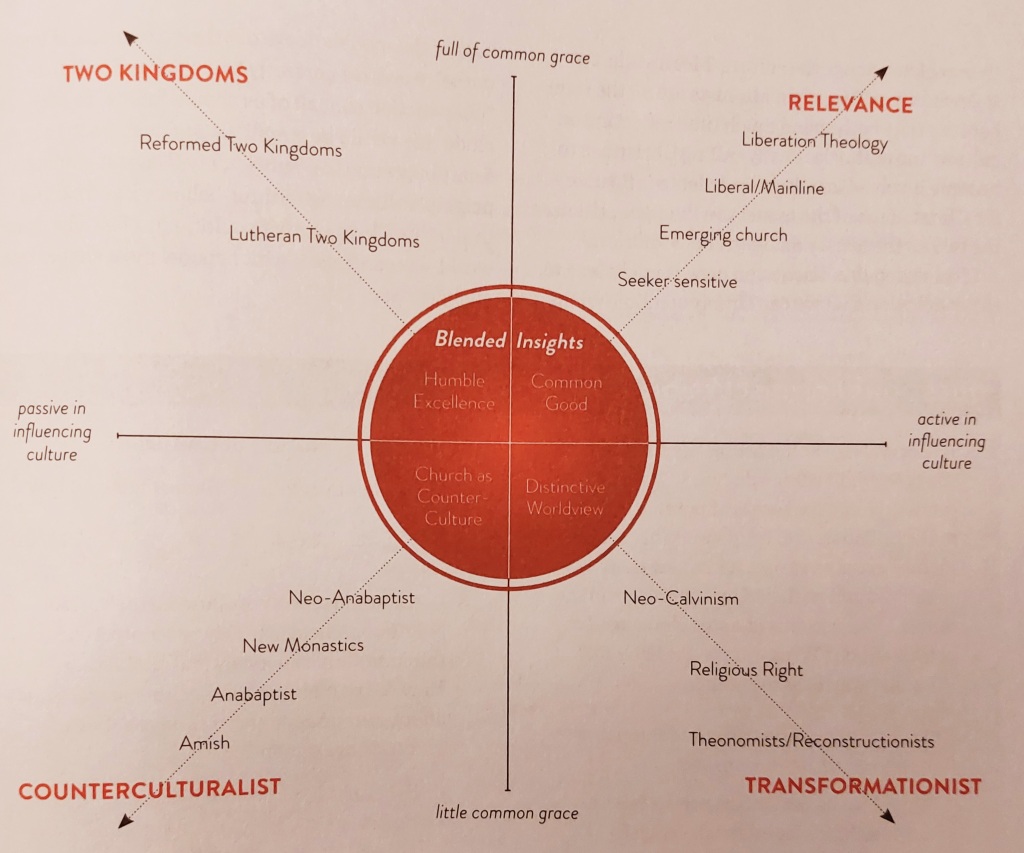

I want to talk about what “the church” is. This will be a high-level discussion, not a defense of a particular kind of church (Baptists v. Methodists, etc.). I want to talk about this because I fear we forget just how important it is to get this right. As sectarian battles light up social media and the news (with no end in sight), this deceptively simple issue deserves some consideration.

There are different ways we use the word “church:”

- The building where the congregation meets. This is common language, and I get it, but it’s wrong.

- In a wholistic sense, considering the entire congregation of the faithful throughout the world. We’ll begin with this.

- In an institutional sense—a local place that exists somewhere. This is the sense which we’ll spend most of our time pondering.[1]

Wholistic Sense—Church as Brotherhood of Christ-followers

Three strikingly different theologians offer up similar definitions for “the church” in a wholistic sense.

Emil Brunner says the church is “a brotherhood resulting from faith in Christ,” and every “church” (viewed denominationally or singly) is but one instrument, vessel, or shell of that brotherhood that spreads that message of redemption.[2] I think this is a beautiful description.

Beth Felker Jones explains a church is “the community that rejoices in God’s gracious salvation … the church is the people of God, called out to bear visible witness, in the body and as a body, to the free and transformative gift of grace we have received in the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ.”[3] Again, simple and beautiful—especially the first portion.

Wayne Grudem writes “[t]he church is the community of all true believers for all time.”[4]

No matter what other sectarian loyalties we’re ready to defend, we must get this right—and these good definitions help us. God’s plan is to gather a community, through Jesus the King, to be with Him in His coming kingdom—forever. He’s been building that community since the Fall, adding to it all the while, across all that space and time. So, God’s congregation (i.e. assembly) is the community of all true believers for all time.

This is important, but now to something more specific—how do you know if you’re in a “good” local church, or a “bad” one?

Individual Sense—Ethos Pentagon + Tyler Heptagon

What I’m really asking is—how much has to change (i.e. go wrong) before “a thing” is no longer “that thing?” We’ll discuss the individual church by looking at it from two different angles:

- Ethos ≈ mood, characteristics, feel (etc.) of the church, and

- Practice—what does the congregation actually do? What are they about?

The Ethos Pentagon

This is a modification of the classic “four marks” of the church, which I’ll call the “Ethos Pentagon.” The Nicene-Constantinople Creed (381 A.D.) set the guardrails for “the church” a long, long time ago. Untold millions of Christians have found it helpful, so we ought to, also: “I believe in one holy, catholic, and apostolic church.”[5] Perhaps the most helpful controlling passage that expresses this ethos is Ephesians 4:1-5.

I’m adding “brotherly love” (inspired by Emil Brunner[6]) as the animating force which drives the four classic marks from Nicaea (cf. 1 Jn 3-4). So, we’re left with a pentagon that looks like this:[7]

Love. This is most clearly seen in 1 John 3-4, which I don’t have space to discuss in detail. “The person who doesn’t love does not know God, because God is love,” (1 Jn 4:8). If this ethos doesn’t animate everything a church does, then it’s nothing, worthless, a fraud (1 Cor 13:1-3; see also Col 3:8-17 (cf. Eph 4:1-5)). Love the fundamental mark of Christianity.[8] Emil Brunner writes:

The Spirit who is active in the Ekklesia expresses Himself in active love of the brethren and in the creation of brotherhood, of true fellowship.[9]

The one thing, the message of Christ, must have the other thing, love, as its commentary. Only then can it be understood and move people’s hearts. True, the decisive thing is the Word of witness to what God has done. But this Word of witness does not aim merely to teach, but also to move the heart.[10]

The song “Proof of Your Love” (by for KING & COUNTRY) sums up this “brotherly love” ethos that should drive the classic four Nicene marks.

A church is only a true church to the extent its attitude, mood, and vibe is one of love for one another, and for the lost. This suggests a congregation with a consistently pugilistic, angry, outraged face towards the world may not even be a “church” at all.

Oneness ≈ Unity. This is an attitude—all Christ-followers are part of the same community, the same brotherhood! Christ is the Head of one body, one community, one congregation—this is why the biblical references are sometimes to one particular congregation, or to all the scattered congregations considered as a whole.

The Church is “one” because Father, Son, and Spirit are One. The Church shares the same faith (Eph 4:5). The Church partakes of the same “loaf” of bread, and the same “cup of blessing” at the Lord’s Supper (1 Cor 10:16-17; Eph 4:5). The Church shares in the same baptism (Eph 4:5). Perhaps it’s helpful to see Christ’s congregation as “one” in the sense that every true church or denomination is a distinct branch of the one tree that is Christ’s body.[11]

You only have a true church to the extent that it recognizes other groups of genuine Christ-followers as brothers and sisters in the same family. This suggests that, to the extent that your congregation is exclusivist, it may well be a false church.

Holiness. We want to “keep Christianity weird” by obeying God’s laws because we love Him. This means we think, live, and act differently than the world around us, because we’re guided by God’s values. Though it’s an anachronism to impute this to Nicaea, we’re essentially talking about the doctrine of separation (rightly understood). Christ wants His church to be pure when He returns (Eph 5:25-27).

A church is only a true church to the extent that it, as a local fellowship, shows God’s love to the world by the transformed lives of its members![12] If a church does not push an ethos of personal and corporate holiness—doing what His word says!—then it may be a false “church.”

Catholic. God’s family is bigger than your tribe—His community has existed since Adam and Eve, across space and time, encompassing millions of men, women, boys, girls—even today! See Revelation 5:9-10 and 1 Corinthians 12:12-27.

We learn from one another, across man-made geo-political, racial, cultural, and gender boundaries because we’re all part of the same family, with gifts to bring to the table! It also means this brotherhood in Christ is meant for the whole world—to be spread everywhere, not ghettoized in a particular area.[13]

Beth Felker Jones writes that we ought to:[14]

- Recognize that no one part of the church is the whole body of Christ.

- Rejoice in the shared doctrine and practice that belong to the whole church.

- Allow differences to flourish, without seeing it as a threat to unity.

- Humbly listen to and be willing to learn from other parts of the body.

- Look for and rejoice in God’s active work in the whole world.

You only have a true church to the extent that it learns from other genuine Christ-followers and works together to spread God’s message. If you believe only your tribe is a “true church,” no matter how finely you try to finesse it, then your “church” may be a false church.

Apostolic. This means holding fast to the true and apostolic teaching about the Gospel and Christian life—Jesus and Peter wouldn’t think your message was crazy.[15] A continuity of belief with the past—built upon the apostles and prophets. Christianity has content—it isn’t playdough (Jude 3; Eph 2:20).

You only have a true church to the extent that it believes, teaches, and lives out what Jesus and the apostles taught. So, for example, the lower your church’s doctrines of major concern rank on Paul Henebury’s Rules of Affinity, the less “true” your church may be.

Who cares? A Methodist and an Anglican will tell us why. Beth Felker Jones explains:[16]

- Unity: in a world of strife, we show God’s love by our love for one another, and mirror God’s own unity.

- Holiness: we show the world the alternative to brokenness and wrongness—God’s holiness.

- Catholic: in a world with emptiness and despair, we invite anyone to the table to share in God’s goodness so we can learn from each other and grow, together—treasuring particularity and differences.

- Apostolic: in a world full of lies, we tell the truth about God and His message of love and forgiveness.

Michael Bird notes the following:[17]

Practice—The Tyler Heptagon

Now, what about practice? I’ve never felt the Nicene marks (even augmented by “love”) was enough to capture what a “true church” ought to be about. So, I’ve gradually developed what I call the “Tyler Heptagon” as a general descriptor for a faithful local church:[18]

The components are not difficult to follow:

- Christ life + death + resurrection: these must be major emphases!

- Scriptures: they’re given by God and are our supreme authority.

- Conversion: emphases on repent + believe + grow.

- Missional: Gospel message and its fruit expressed in a “conscience of the kingdom” ethos in society. This is a major failing for too many local churches. If you have no practice of evangelism, your church is derelict in its duties. I’m not referring to fruit per se—I’m talking about effort. Are you doing anything, or is evangelism a passive wish?

- Praise to God: this must be a major emphasis!

- Right practice: a reformation, “always reforming” mindset—not a faith expression and doctrine set in immobile concrete.[19] Whatever you might say, if your every reaction to anything “new” or “other” as related to your faith tradition is immediate hostility and a “run away!” mindset, your feet are set in concrete.

- Right heart and motivations: These are affections—an honest love for God must be behind everything we say and do … or else we get everything wrong.

What Does This Mean?

When you consider both ethos and practice, to the extent these things aren’t there, or are weak, your church is unhealthy or maybe even false. In a shadowy but indefinable way, at some point if enough of these things are weak or missing altogether, you don’t have a true church at all.

Think about it this way—at what point is a car a junker? When the seatbelt won’t buckle unless you slam it really hard? When the sliding doors on the minivan won’t open, anymore? When it won’t start consistently? In isolation, these aren’t deal-breakers. But, when they’re all persistently there, at some point you stand back and admit, “yeah … this car is a piece of junk!” You didn’t realize it until that moment, and maybe you can’t pin down the exact moment the car became a piece of junk. But, still … now you wake up and realize you drive a piece of junk car.

As you consider ethos and practice, it’s the same with a local church. The state of a church—at what point it “becomes” unhealthy or perhaps even false—is a totality of the circumstances assessment, and a number of factors could push it across the line. Perhaps these two metrics, ethos and practice, will help as you consider how to make your own church healthier.

Our churches will never be perfect. But, they can all be better. Let love inform your ethos. Doctrine without love is nothing. Purity without love is nothing. A church that doesn’t evangelize is derelict. A rigid dogmatism without heart is death. A closedmindedness to further reformation is no virtue. Let’s make our churches be more about Jesus than a reflection of our sectarian battlelines.

[1] Emil Brunner doesn’t like to consider the church from an institutional perspective, preferring instead to speak in a wholistic sense of a brotherhood of all who share faith in Christ. To him, the institutional church is the shell or instrument of the ecclesia. I get what he’s saying, but when it gets down to brass tacks, out of the clouds, people need to know when they’re in a true, bona fide, legitimate local assembly. We must speak of the church on the local, institutional basis, too. So, here I stand.

[2] Brunner, The Christian Doctrine of the Church, Faith, and the Consummation, p. 128ff.

[3] Beth Felker Jones, Practicing Christian Doctrine: An Introduction to Thinking and Living Theologically (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2014), p. 195.

[4] Grudem, Systematic, p. 853.

[5] Πιστεύομεν … εἰς μίαν ἁγίαν καθολικὴν καὶ ἀποστολικὴν ἐκκλησίαν.

[6] See my article “Brotherly Love and the Church.” 23 October 2020. https://bit.ly/3qhLzdy.

[7] For my discussion of the four marks, I’m generally following Michael Bird as a base unless I specifically note otherwise (Evangelical Theology: A Biblical and Systematic Introduction (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2020),pp. 833-842.

[8] The Cape Town Commitment (2010) reads: “The people of God are those from all ages and all nations whom God in Christ has loved, chosen, called, saved and sanctified as a people for his own possession, to share in the glory of Christ as citizens of the new creation. As those, then, whom God has loved from eternity to eternity and throughout all our turbulent and rebellious history, we are commanded to love one another. For ‘since God so loved us, we also ought to love one another,’ and thereby ‘be imitators of God…and live a life of love, just as Christ loved us and gave himself up for us.’ Love for one another in the family of God is not merely a desirable option but an inescapable command. Such love is the first evidence of obedience to the gospel, the necessary expression of our submission to Christ’s Lordship, and a potent engine of world mission,” (Article 1.9, https://lausanne.org/content/ctc/ctcommitment#p1-9).

[9] Brunner, Church, Faith, and Consummation, p. 134.

[10] Brunner, Church, Faith, and Consummation, p. 136.

[11] This is what Alister McGrath calls the “biological approach” to oneness (Christian Theology: An Introduction, 3rd ed. (Malden: Blackwell, 2001), p. 497).

[12] “When the church is holy, we bear visible and material witness to God’s love for the world,” (Jones, Christian Doctrine, p. 201).

[13] Brunner, Church, Faith, and Consummation, pp. 122-123.

[14] Jones discussed this under a “ecumenical” heading in the introduction to her systematic theology (Christian Doctrine, pp. 4-9), but I co-opted it as a great shorthand to describe the catholic ethos a church ought to have. Hopefully, she’ll forgive me! This is quoted nearly verbatim—it isn’t my paraphrase.

[15] Michael Svigel helpfully suggests seven teachings that summarize the Christian message: (1) the triune God as Creator and Redeemer, (2) the fall and resulting depravity, (3) the person and work of Christ, (4) salvation by grace through faith, (5) inspiration and authority of Scripture, (6) redeemed humanity incorporated into Christ, and (7) the restoration of humanity and creation (RetroChristianity: Reclaiming the Forgotten Faith (Wheaton: Crossway, 2012), pp. 175-176).

[16] Jones, Christian Doctrine, pp. 203-204. What follows are my summaries of Jones’ comments—they aren’t quotes.

[17] Bird, Evangelical Theology, p. 842.

[18] This began life as my own re-phrase of what I call the “Stackhouse hexagon,” which was itself inspired by David Bebbington (John Stackhouse, “Generic Evangelicalism,” in Four Views on the Spectrum of Evangelicalism, ed. Andrew Naselli and Collin Hansen (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2011), pp. 123-124). However, it’s been colored by so much reading, and I’ve added and subtracted and modified so much, that I feel free to give it my own label, at this point. Stackhouse (and Bebbington) used their models as theological descriptors of evangelicalism. In my modification, I use it as a model for a “generically faithful local church.”

[19] See especially Roger Olson on the perils of a “conservative” mindset that, in functional practice, believes the Spirit has nothing new to teach the church to better live out the Christian faith as revealed in Scripture (How to be Evangelical Without Being Conservative (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2008), pp. 13-42).